Despite State Barriers, Cities Push to Expand High-Speed Internet

Across the country, 39 percent of rural residents and 50 percent of the lowest-income residents lack access to high-speed internet.

This article was originally published at Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, and was written by Jen Fifield.

Websites take minutes to load and photos take hours to upload at Ryan Davis’ home in the small southern Tennessee city of Dayton. If Davis gets in his car and drives about half an hour south to Chattanooga, though, everything takes under a second.

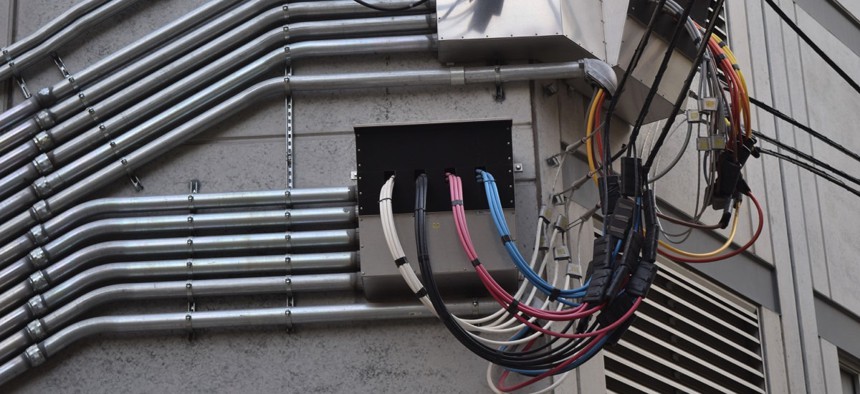

The city-provided fiber optic network there is so fast — up to 10 gigabits per second — that Chattanooga is known as Gig City. Chattanooga wants to expand outside of its current service area to Dayton and other rural spots. But a state law bans cities from doing so, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit last month rejected an attempt by the Federal Communications Commission to block the state law.

The court’s decision was limited to Chattanooga and Wilson, North Carolina, another city that wants to expand its service. But about 20 states have laws that ban or restrict municipal broadband, and the ruling means that any city that attempts to get around the laws won’t be able to turn to the federal agency for help.

The outcome sends the fight back to the local level, where cities are looking for ways to work within the laws so they can reach residents on the other side of the digital divide.

Madison, Wisconsin, hired a private company that this month will start bringing low-cost, high-speed internet to low-income neighborhoods. Holland, Michigan, is studying how much it would cost to provide service there, despite a state law that makes it hard for cities to do so. And voters in at least 35 Colorado cities and towns have passed ballot measures in the last year that will allow them to ignore their state law.

Local officials, such as Chattanooga Mayor Andy Berke, a Democrat, say that expanding access to broadband not only attracts new people and companies but also inspires innovation from existing residents and businesses, ultimately creating jobs and other economic opportunities. And, they say, they are bringing high-speed internet to places that the private sector has chosen to ignore.

Across the country, 39 percent of rural residents and 50 percent of the lowest-income residents lack access to high-speed internet, compared to 4 percent of urban residents and 23 percent of the highest-income residents.

Advocates for restrictions on municipal broadband, including Republican state lawmakers and free-market think tanks, say the rules are needed to keep the government from unfairly competing with businesses, which are subject to state and local regulations and taxes that many cities don’t face.

Some states that already have limits on municipal broadband, such as Colorado and Wisconsin, are taking further steps to ensure that private companies are competitive with public networks, including loosening regulations or making grants to companies that promise to expand to underserved areas.

The laws were also meant to protect cities from taking on expensive ventures that may fail, as they have in many cities, said Lawrence Spiwak, an economist and the president of the Phoenix Center for Advanced Legal and Economic Public Policy Studies, which has studied municipal broadband.

“It’s playing with taxpayer money,” Spiwak said.

Local Options

State laws blocking municipal broadband vary. Some allow counties and cities to offer broadband, as long as they first get voter approval or check that private companies don’t want to add service in the area. Others ban the government from entering areas where there are already private providers.

In Michigan, cities have to take multiple steps before they can offer broadband, including issuing a request for proposals from the private sector, and completing a cost-benefit analysis. Despite the obstacles, some cities are moving forward.

Holland launched a pilot project last year that is using an existing fiber optic network that offers internet speeds nearly as fast as Chattanooga’s and is studying how to expand that service citywide. Neighboring Laketown Township is considering building its own network.

In Fort Collins, Colorado, 83 percent of voters supported a ballot initiative last year to allow the city to provide broadband. The city is now studying the demand for broadband and different options for how to provide service, such as building and running the service itself, building a fiber optic network and then trying to get a private partner, such as Google Fiber, to move in, or simply recruiting a company like Google to build and run the network.

In some places, though, Google is running into issues gaining access to utility poles that are often owned by other companies and regulated by local and state governments. Such obstacles are making city officials see more clearly that the private sector alone can’t close the gaps in service, said Christopher Mitchell, policy director at Next Century Cities, a nonprofit that advocates for more high-speed internet.

One way for cities to get around laws in many states is to support a cooperative model, where customers own the network, Mitchell said. A city could build the fiber optic network and agree to lease it to the co-op at a low rate. Or, it could take out a bond and make a loan to the co-op to build the system.

One successful co-op model, Mitchell said, is in Minnesota, where multiple cities and towns funded a bond and made a loan to the RS Fiber cooperative, which aims to bring high-speed internet to rural communities. The disparity in the state between those who have access to broadband and those who don’t is extreme — just 1 percent of urban residents lack access, compared to 43 percent of rural residents.

Some States Help

About five years ago, many states created broadband departments or paid for studies to see where service was lacking. Although some of those efforts fizzled out, some states have started to act on what they found.

In New York, Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo wants to connect everyone in the state to broadband by the end of 2018. Lawmakers last year passed a budget that included $500 million for this purpose, starting with $54.2 million for the first round of projects.

In West Virginia, where 30 percent of residents don’t have access to broadband — the third highest percentage of all states — Republican state Sen. Chris Walters has the same idea. He introduced a bill this year that would allow the state to issue bonds to build sections of one long fiber optic line, which would run across the state, including through its mountainous rural areas, so that counties, cities or service providers have a shorter route to high-speed internet.

Walters and other lawmakers say they have started to view high-speed internet as a core service, similar to water and electricity.

“If you don’t have access to the internet, you don’t have access to socialization, to opportunity,” he said.

Yet service providers have good reasons to avoid some rural areas, Spiwak said. The demand isn’t there, and it’s expensive to build new networks.

Officials in Provo, Utah, ended up selling the city’s network to Google Fiber for $1, after the network ran out of money. That left taxpayers on the hook for $3.3 million in bond payments per year for 12 years.

Advocates for municipal broadband say lawmakers who supported state laws that limit municipal broadband were influenced by campaign donations and lobbying from large internet companies, who want to prohibit competition in markets where there often isn’t any.

In North Carolina, where lawmakers passed a law in 2011 restricting municipal broadband, an investigation by the National Institute on Money in State Politics found that groups connected to telecommunication companies gave $1.6 million to state candidates and $97,725 to state political parties, from 2006 to 2011. AT&T alone gave $520,438.

AT&T was also a proponent for the law that restricts cities and counties in Tennessee. Public networks should be limited to locations where private sector service is not available and is not likely to be available in a reasonable time frame, said Joe Burgan, an AT&T spokesman.

“Governments should concentrate on investing taxpayer dollars in areas such as education or public safety, not in competing with or overbuilding the private sector, which has a proven history of funding, building, operating and upgrading broadband networks,” Burgan said in a statement.

Disconnected

Other providers had served Chattanooga and Wilson before the governments there stepped in, but local officials say the service had been inadequate. The cities asked the FCC to exempt them from state laws that restrict their efforts to expand internet service. In 2015, the FCC said that the cities could expand, and that the states couldn’t stop them.

After getting that go-ahead, Wilson connected service to the nearby town of Pinetops; and Chattanooga took requests from residents outside the city who wanted to be connected.

One of those residents was Ryan Davis, who wanted to expand his side business of selling guns and ammo, by increasing his online sales. With the slow internet speed at home, he said it could take all day to add information about a product to his website.

Despite last month’s Court of Appeals ruling, which overturned the FCC decision, Berke in Chattanooga thinks there may still be hope for Davis and his neighbors.

Advocates for municipal broadband this year introduced two bills, in the Tennessee Legislature, that would have allowed municipalities to provide internet service outside their area. The measures were put on hold, but Chattanooga and six other communities in the state are expected to make a similar push next year.

In addition, Republican state Sen. Mark Norris has commissioned a study to identify a broader solution to the lack of broadband access in the state. Other changes need to be considered to make it easier for businesses to compete, Norris said, such as eliminating regulations and cutting taxes.

“You want it to be an effective playing field,” Norris said. “Finding that sweet spot is the challenge.”

NEXT STORY: Florida's Zika Image Problem