Should the Federal Government Be Funding Private Sports Stadiums?

Yankee Stadium is seen in 2014. Flickr user dex07

A new report says there's a better use for $3.7 billion.

This is what Yankee fans gained when the doors to their new stadium opened in 2009: seats that were two inches wider, a .5 percent increase in the number of bathrooms per fans, and a Hard Rock Café in which to while away slow innings.

But it didn’t come free, and according to a new report from the Brookings Institution, the federal government footed a large part of the bill. Around $1.7 billion of the total $2.5 billion in construction costs for the stadium overhaul was financed by tax-exempt municipal bonds issued by the city of New York. If those bonds had been taxable, the government would have earned $431 million; instead, that money was funneled straight into the stadium. To add a little bit of extra sting, the government lost an additional $61 million in revenue from the windfall tax breaks issued to high-income bond holders.

Public financing of private sports stadiums is a well-documented source of frustration; CityLab’s Richard Florida previously wrote that “The overwhelming conclusion of decades of economic research on the subject is that using public funds to subsidize wealthy sports franchises makes zero economic sense and is a giant waste of taxpayer money.” An estimated $12 billion in public money has been used to finance stadiums over the past 15 years, and the Brookings report places the federal tax revenue loss resulting from these projects at $3.7 billion.

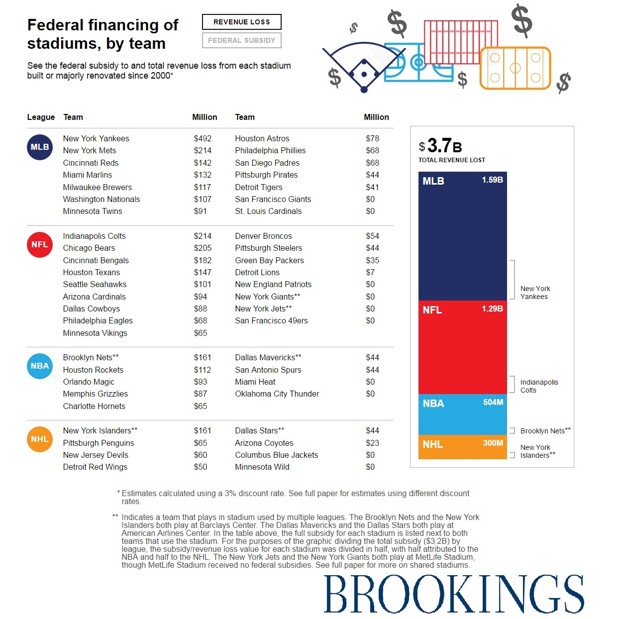

Of the 45 stadiums built or renovated since 2000, 36 were financed using tax-exempt bonds. The Brookings report quantifies the federal subsidies allotted to each project, and the resulting losses in tax revenue.

While Yankee Stadium was easily the most expensive, 12 of the 36 stadiums received six-figure subsidies resulting in equally staggering revenue losses. At $1.59 billion in total revenue losses, the MLB gouged the biggest dent, followed by the NFL, the NBA, and the NHL (view the interactive here).

Total revenue loss by team and league. (Brookings Institution)

This is a good deal of money to be messing around with, says Ted Gayer, lead author on the report.

A cross-state bridge or infrastructure project, Gayer says, should receive federal funds; in contrast, stadiums—which have spillover benefits for a much smaller locality—should be subsidized by the people they serve, he adds. “You can even talk about public parks, say, having some sort of intrinsic value nationwide,” Gayer says. “I might not go to a public park in Alaska, but it might mean something to me that it’s kept pristine.” Conversely, he says, “there’s no doubt that a stadium does not have cross-state public benefits.”

The stoking of intense local fanaticism aside, stadiums offer few benefits even at the city level. “Proponents of government subsidies for sports stadiums typically justify them on the grounds that stadiums provide spillover gains to the local economy,” Gayer wrote in the Brookings report. But he added that “academic studies consistently find no discernible positive relationship between sports facility construction and local economic development, income growth, or job creation.” Even if one persists in believing stadiums offer spillover economic benefits, Gayer wrote, there’s no justification to keep throwing federal money at them.

Stadiums are the playhouses of professional sports leagues, which are, at their core, very profitable businesses. As such, Gayer says, the solution to what CityLab has previously termed “the never-ending stadium boondoggle” is to treat them like corporate properties, not public goods. “Stadiums should not be eligible to receive tax-exempt bonds,” Gayer says. While professional sports leagues still have ties to federal funds, the idea that they one day might be divorced is not inconceivable; in both his 2015 and 2016 budgets, President Obama proposed repealing the tax exemption for stadiums.

Fundamentally, stadiums are private enterprises that only benefit select groups of people. As Gayer noted in the report: “Residents of, say, Wyoming, Maine, or Alaska have nothing to gain from the Washington-area football team’s decision to locate in Virginia, Maryland, or the District of Columbia. So why is the federal government still subsidizing their construction?”

(Image via Flickr user dex07)