Is This Vermont City's Refugee Resettlement Plan Sustainable?

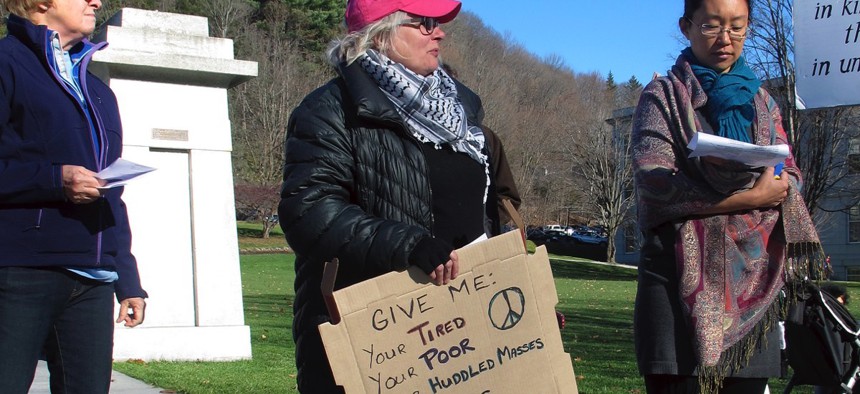

Crystal Zevon, center, holds a sign on Nov. 20, 2015, at a rally outside the Statehouse in Montpelier, Vt., where she supported bringing resettling Syrian refugees. Wilson Ring / AP Photo

Part 2: Resettling 100 refugees could be complicated if there isn't adequate affordable housing or employment. “There are so many unanswered questions,” according to Alderwoman Sharon Davis.

This is the second in a two-part series on refugee resettlement in Rutland, Vermont. Read Part I here.

By the time Rutland, Vermont Mayor Chris Louras announced that a nonprofit agency had selected the city as a possible resettlement site for foreign refugees, it was late April of this year.

It had been about five months since Louras first contacted Gov. Peter Shumlin’s office to begin discussions about Rutland opening its doors to refugees from Syria and elsewhere. During that time, the mayor had some limited conversations with community leaders and others about refugees relocating to the city. But there’d been no widespread public debate on the issue.

With Louras’ announcement, word about the resettlement plan was out.

The U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, the nonprofit agency, would submit an application to the U.S. Department of State, proposing Rutland as a place where up to 100 refugees would relocate to during the 2017 federal fiscal year, which runs Oct. 1 to Sept. 30.

Heated discussions ensued, with community members both backing and opposing the plan.

Board of Aldermen meetings drew packed crowds. And board members complained they’d been left out of initial talks about refugee resettlement and that they'd been “blindsided” by the proposal.

An Alderwoman’s Perspective

Alderwoman Sharon Davis has served on the Rutland Board of Aldermen for about 26 years, through the terms of three different mayors.

“For weeks, every time the board met, there would be 100 people in the aldermanic chambers,” she said by phone in September, describing the reaction to the resettlement plan. “It would be three hours of listening to how wonderful it’s going to be and how horrible it’s going to be.”

The board voted 7-3 in July to send a letter telling the State Department it was withholding support from the plan, citing a lack of information.

Davis blamed Louras for the blowback.

In her view, if the mayor had been more forthcoming about his interest in establishing Rutland as a refugee resettlement site early on, much of the controversy could have been avoided.

The way she sees it, Louras delayed broad discussions until it was too late for the proposal to be stopped.

“He did this very poorly,” she said of the mayor.

Davis said she is not necessarily against refugees resettling in Rutland—even 100 in the current fiscal year. But what she has wanted to see is evidence that the plan will be sustainable for the city.

“There are so many unanswered questions,” Davis said. “And there’s so much secrecy and lack of transparency.”

She voiced uncertainty about how it was determined 100 refugees should be resettled in the city: “What is it based on?”

And she questioned how many displaced individuals might arrive in future years. “I don’t know that we have the resources to serve 100, and 100 every year.”

Davis also outlined concerns she had about possible taxpayer costs for schools to accommodate students from resettled families, how new arrivals would affect residents currently in need of low income housing, and whether there were, in fact, adequate jobs available in and around Rutland for former refugees to fill.

An Imperfect Calculation

Stacie Blake, director of government and community relations for USCRI, said by phone in early October that when the nonprofit resettlement agency determines the number of people it will initially seek to resettle in a location it tends to be an “imperfect calculation.”

“It’s based on experience and what we have seen to provide a good start for new families,” she added.

There is no formula that says if there is a set number of jobs or homes available, then a community can support a certain number of families.

“It’s not that precise,” Blake said.

Some of the factors taken into account when assessing a potential resettlement site do include local labor and housing market conditions, as well as public transit access and cost of living.

Blake noted that resettling a smaller number of people, like 10, in a location might equate to just two families, which could leave those individuals feeling isolated. So few people in a place would also make it tough to justify a USCRI office with two or three staff members.

Organizations like USCRI, along with local affiliates, help resettled refugees with a range of tasks, like securing housing, registering kids for school, preparing for job interviews and enrolling adults in English classes. “It’s a lot of logistical arrangements,” Blake said.

In future years, according to Blake, the number of refugees who relocate to Rutland will depend in part on outcomes tracked by the State Department for displaced people who have already moved to the city. For instance, employment rates and pay and benefit levels.

Other metrics are monitored as well, such as whether the local resettlement program has helped former refugees to obtain Social Security cards, and to schedule necessary medical appointments.

Blake said feedback from community members, including elected leaders, education officials, landlords and employers also comes into play.

Some critics have warned that terrorists might use the refugee resettlement system as a gateway into the U.S.—a worry heightened by the fact that the Islamic State terror group, or ISIS, has been active in Syria.

As a bulwark against this possibility, refugee applicants undergo the highest level of screening and background checks of any traveler allowed into the country, according to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

Blake said refugees could begin to arrive in Rutland between mid-December and early January. It’s anticipated that most will be Syrian and some could be Iraqi.

After the plan for a resettlement program in the city gained the federal government’s blessing in late September, Davis, the alderwoman, acknowledged: “We’re now a resettlement town.”

“The board can’t stop this,” she added. “Hopefully we’ll get a better handle on how it’s going to function.” But Davis also said: “If people are coming to our city, we certainly will welcome them.”

‘Driven to Work’

Past efforts to assist refugees who have resettled elsewhere in Vermont offer a window into what could unfold in Rutland. Along with USCRI, and smaller nonprofits, the state has played a role in this work.

Most of the refugees who have previously moved to the state relocated to Chittenden County, which is north of Rutland and encompasses the city of Burlington.

Denise Lamoureux, Vermont’s refugee coordinator, recently described by phone the performance of an employment services program the state oversees for former refugees.

At the end of the 2015 federal fiscal year, she said, 209 of the 294 people enrolled in the program, or about 71 percent, had found jobs. Lamoureux stressed that this is one of several programs meant to help former refugees in Vermont access employment and benefits.

Eskinder Negash, senior vice president for global engagement at USCRI, has been involved in refugee resettlement for about 37 years. He emphasized that former refugees are typically eager to find jobs.

“They are not interested in getting some food stamps,” he said. “These are people driven to work, they want to work, and they want to earn money.”

But roadblocks can arise.

Jacob Bogre is executive director of Burlington-based AALV Inc., a group that works with refugees and other immigrants in the area.

Last year, the organization assisted 386 individuals, 320 of whom were former refugees.

“The primary difficulty they are facing is related to language,” Bogre said. “They have limited English and that makes it difficult sometimes.” This, he explained, can mean newly arrived adults end up taking temporary work while studying English as a second language.

Another common problem, he said, is that people who were qualified for professional jobs in their home country are unable to easily get recertified in the U.S. “If they want to go back to their same field,” he said, “they have to go back to school, which would take a lot of time.”

People who formerly worked as doctors, nurses, teachers and engineers can end up in this predicament, according to Bogre.

He said many of the jobs available in the Burlington region are in the hospitality industry, in hotels for instance, or in factories, such as one that makes clothing near the Canadian border.

A Former Refugee’s Perspective

Kanoka Kamikazi has been in Vermont since 2009 and lives in the city of Winooski in Chittenden County. Kamikazi left the city of Uvira in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1996, around the time the First Congo War engulfed the eastern part of the country.

From Uvira, Kamikazi went to a refugee camp in the Kigoma Region of Tanzania.

There she spent about 10 years living with her three children.

“It was not comfortable,” she said of the camp, during a recent phone interview. “You come from your house, your family, life changed … everything was worse.”

When she and her children first arrived in the U.S. in 2006, they lived in Massachusetts before moving to Vermont.

Kamikazi said she previously found part-time work in a cafeteria at the University of Vermont, where she started out as a dishwasher. At the time, she said, her English wasn’t good.

She later moved on to a job as a hospital housekeeper. “I was happy with that, I was making good money,” she said. But after injuring her back on the job, Kamikazi has been out of work.

Her kids are grown now and are between 20 and 26 years-old. They each have jobs.

She said her daughter works as a caregiver in a nursing home and has about a year left before completing a degree at Champlain College. One of her sons is a cook in a restaurant and is studying to be a dental assistant. The other works in a factory that makes cosmetics.

Although Kamikazi likes Vermont, she said it is expensive to live there and that buying a house is not an affordable option right now for her or her children, so they rent.

Despite the cost of living, she said: “I’m happy to be here in the United States.”

“Because of my kids,” Kamikazi added. “They’re happy.”

But she did highlight one worry that currently weighs on her.

Some of the talk in this year’s presidential election cycle makes her nervous that something could change, which would force her and her family to leave the country. Other immigrants she’s spoken with have voiced similar fears, she said.

“This is a different election,” Kamikazi said. “It’s very, very scary.”

A Local Election Next Spring

Louras thinks if the resettlement proposal for Rutland was rolled out two years ago, it would not have generated such an intense reaction.

What’s the difference today?

“The fact that immigration and refugee resettlement is such a huge part of the unfortunate language at the national level has created that same dynamic here at the local level,” Louras said.

He specifically mentioned “the misinformation, the rhetoric bordering on vitriol...as stoked by the Republican candidate Donald Trump.”

Louras is not a Democrat. The mayoral election in Rutland is nonpartisan. But he previously served in the state legislature as a Republican. “I identify more closely with the principles of the Vermont Republican party,” than with Democrats or progressives, he said.

Some of the mayor’s critics are looking toward an election beyond November—a local one that will take place in March 2017. Louras plans to compete then for a sixth two-year term.

Davis said that “every member of the voting public” should read a review from the City Attorney’s Office describing Louras’ actions related to the refugee resettlement plan.

“They’re going to have to make that political decision come March,” she of city voters.

Louras brushed aside suggestions he could have put himself at political risk backing the resettlement proposal. “I don’t worry about reelection campaigns,” he said. “Haven’t even given it any thought whether this would be a negative or a positive. This is the right thing to do.”

Bill Lucia is a Reporter at Government Executive's Route Fifty and is based in Washington D.C.

NEXT STORY: 400 Murderers to Be Re-Sentenced in Florida?; N.C. Governor's HB2 Emails Revealed