Drug Prices, Senior Programs May Deliver Blow to State Budgets

Connecting state and local government leaders

Recent changes in federal programs for seniors could drive up states’ Medicaid costs by millions of dollars.

This article was originally published at Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, and was written by Michael Ollove.

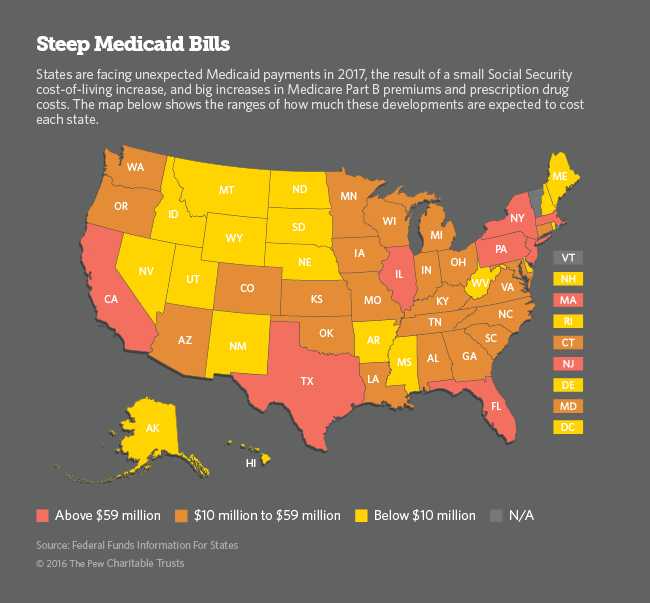

Higher prescription drug prices, combined with changes to Medicare and Social Security, could deal a $1.6 billion blow to state budgets next year by forcing them to ratchet up spending on Medicaid, the federal-state health care program for the poor.

Without congressional intervention, most state Medicaid agencies will have to come up with tens of millions of dollars to cover the bill.

The new costs could prompt states to tighten eligibility requirements or cut benefits. They could, for example, reduce dental benefits under Medicaid, which they aren’t required to offer, or shift more prescription drug costs to patients. They also could cut payments to doctors, which might prompt more providers to stop treating Medicaid patients.

The new costs come at a time when many states already are experiencing budget strains.

Connecticut, where revenue is falling about $650 million short of projections this budget year, will have to find $29 million to cover additional Medicaid costs, according to an analysis by the Federal Funds Information for States. (FFIS is a research organization that provides financial analysis for state governments.)

In West Virginia, where Democratic Gov. Earl Ray Tomblin last week ordered a 2 percent spending cut across the board to make up an $87 million shortfall, the extra costs were projected at $6.6 million.

In Kansas, where revenue is $345 million short of estimates this budget year, additional Medicaid costs were projected at $11.2 million. Kansas’ total Medicaid spending was about $1.3 billion in fiscal 2016, according to the governor’s office.

For California alone, the double whammy of the increases in Medicare Part B premiums and Medicare drug spending is projected to saddle the state with an additional cost of $293 million. California’s total Medicaid spending was almost $34 billion in 2015.

States are just now receiving federal estimates of their Medicaid costs, and many are hoping the lame-duck U.S. Congress will step in to provide relief.

“I don’t think there’s an expectation [that Congress will act], but there is a hope that they will,” said Matt Salo, executive director of the National Association of State Medicaid Directors. “If they don’t, there’s going to be a lot of upset people in the states looking under couch cushions for extra money.”

For now, states are still grappling with the implications.

“We’re still taking it in,” said H.D. Palmer, a spokesman for the California Department of Finance. Officials had similar responses in Connecticut, Florida and Kansas.

Eileen Hawley, press secretary to Kansas Republican Gov. Sam Brownback, complained about the “negative effect” the Affordable Care Act has on Kansas’ budget. But the increase in state spending related to Medicare pertains to legislation that preceded the ACA.

Rising Prescription Spending

About $1.2 billion of the $1.6 billion projected Medicaid hike for the states is the result of higher prices for prescription drugs in Medicare, the federal health plan for the elderly and disabled people. Medicaid and therefore the states are affected by a group of “dual eligible beneficiaries,” who receive both Medicare and Medicaid benefits because of their low income.

When Medicare added prescription drug benefits in 2006, called Medicare Part D, Congress determined that state Medicaid agencies would have to pay the Part D premiums of the dual eligibles.

Late last month, the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announced that the state responsibility for Part D premiums would increase by nearly 12 percent next year. The increase marks the second year of increases by a double-digit percentage and the largest annual increase since Part D began. That accounts for the projected $1.2 billion bill for the states, according to the FFIS analysis.

Rising prescription drug prices are a broader phenomenon. From 2013 to 2016, drug spending in the U.S. increased by 27 percent, according to U.S. Department of Health and Human Services estimates. Expensive new specialty drugs (like those that cure Hepatitis C and treat various forms of cancer) were cited as helping to drive up costs.

The rapid rise in drug prices is catching many states by surprise, according to John Hicks, executive director of the National Association of State Budget Officers. “If any states were planning for this, I’m not aware of them,” he said.

A Rare Occurrence

The rest of the projected new Medicaid costs — approximately $490 million, according to FFIS — are the result of recently announced and interrelated developments. One was the tiny cost-of-living adjustment (a 0.3 percent increase) to Social Security payments. The other was the 10 percent increase to Medicare Part B premiums for some beneficiaries. Part B covers doctor visits and laboratory tests for the nation’s seniors and disabled. The 10 percent increase is the largest since 2010.

Social Security and Medicare are separate from Medicaid, which covers nearly 73 million low-income Americans. But a Rube Goldberg system of overlapping federal rules connects the three programs.

Under law, premiums paid by Part B beneficiaries must cover about one quarter of the program’s costs. When the costs of Part B go up, so do the premiums — except in one particular and rare circumstance.

Federal law protects most Part B beneficiaries from premium increases that exceed their annual Social Security cost-of-living bumps. So, for instance, if the Social Security benefit increases by $5 a month but the premium goes up by $10 a month, most Medicare beneficiaries would only have to pay an extra $5 a month, rather than $10.

This “hold harmless” provision applies to about 70 percent of Part B beneficiaries. The remaining 30 percent must cover the entire premium increase — not just their own but the part of the increase not paid by the other 70 percent. The unlucky 30 percent includes dual eligibles.

Under federal law, Medicaid is responsible for paying the Part B premiums of the dual eligibles. So in the rare years, such as 2017, when Part B premiums rise more steeply than Social Security benefits, state Medicaid programs are on the hook for additional costs.

The same thing would have happened this year, but Congress stepped in to prevent it.

States and groups that advocate for seniors, such as AARP, are asking federal lawmakers to intervene again.

“My guess is that with everything else going on right now, this probably isn’t Congress’ highest priority,” said Juliette Cubanski, associate director of the program on Medicare policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonprofit that analyzes health policy.

NEXT STORY: This City in Oregon Will Be Mostly Destroyed in a Future Tsunami. But There's Some Good News.