How Did North Carolina's Deal to Repeal H.B. 2 Fall Apart?

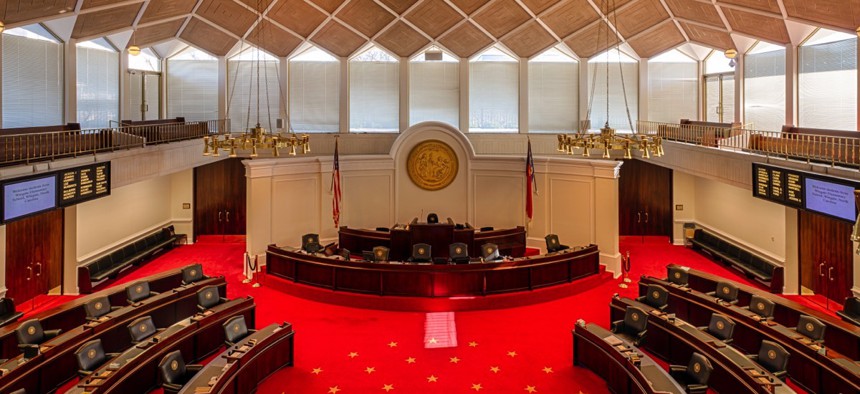

The senate chamber of the North Carolina State House.

An attempt to roll back the state’s controversial “bathroom bill” collapsed amid recriminations on Wednesday.

DURHAM, N.C.—Christmas is a time for stories about unity overcoming divisions, about miracles that can bring everyone together with a heartwarming conclusion.

This is not one of those stories.

Last week was a bruising one for North Carolina politics. After returning to Raleigh for a special session intended to pass disaster relief, the Republican leaders in the General Assembly used the occasion to ram through a series of measures to strip the incoming governor, a Democrat, of powers they had afforded the outgoing governor, a Republican. It was brazen power politics, a fact the GOP didn’t dispute, and it brought widespread national disapprobation on the state.

This week started out looking more positive: There were signs of a deal to repeal H.B. 2, the “bathroom bill” that had fiercely divided the state and produced hundreds of millions of dollars in economic losses. In February, the city of Charlotte passed an ordinance barring LGBT discrimination, including a provision that mandated that transgender people be allowed to use bathrooms corresponding with the sex with which they identify. The GOP-led General Assembly quickly called a special session in which it barred cities from passing LGBT nondiscrimination ordinances (or, for good measure, higher minimum wages), and mandated that transgender people use bathrooms corresponding to the sex on their birth certificate in any public facilities. The law set off boycotts, protests, and acrimony, and is one reason Governor Pat McCrory, a Republican, lost his bid for reelection last month.

On Monday morning, with no advance warning, Charlotte’s city council convened and (reportedly) passed a repeal of the offending ordinance, contingent on the General Assembly repealing H.B. 2. Governor-elect Roy Cooper, a Democrat, issued a statement saying that the GOP leaders in the General Assembly had promised him they’d convene a special session on Tuesday to fully repeal H.B. 2. Cooper had reportedly also lobbied city-council members to repeal the ordinance.

It was a big gamble for the governor-elect: If he won, he would have his first major victory under his belt even before he was sworn in, slaying an unpopular law. But to do that, he had to rely on the same GOP leaders who had stealthily hatched a plan to strip Cooper of his gubernatorial powers the week before.

The first sign that Cooper’s gamble might be ill-advised came Monday afternoon, when Senate President Pro Tem Phil Berger and House Speaker Tim Moore issued a joint statement. “For months, we’ve said if Charlotte would repeal its bathroom ordinance that created the problem, we would take up the repeal of H.B. 2,” they said. “But Roy Cooper is not telling the truth about the legislature committing to call itself into session—we’ve always said that was Gov. McCrory’s decision, and if he calls us back, we will be prepared to act. For Cooper to say otherwise is a dishonest and disingenuous attempt to take credit.”

Though Cooper had initially said the General Assembly would meet Tuesday, the special session was pushed back to Wednesday. Even before the meeting occurred, pessimism began to well up. Republicans hold large majorities in both houses of the legislature, and it was not clear that there were GOP votes for repeal in both chambers—or even in either one. That meant leaders would either have to rely on Democratic votes or, more likely, caveat “full repeal” to win Republican votes.

There was trouble in Charlotte as well. First, the city council may have violated public-notice laws with its sudden meeting, which is one reason that it was not immediately apparent that rather than repeal the whole ordinance, the council had only repealed the bathroom provision. Second, the city risked arousing the legislature’s ire, both by making their repeal contingent on H.B. 2 repeal, and with a statement in which the council more or less promised to just pass the same ordinance again once H.B. 2 was gone. “The City of Charlotte is deeply dedicated to protecting the rights of all people from discrimination and, with House Bill 2 repealed, will be able to pursue that priority for our community,” members said in a statement. Members of the Durham city council also said they would quickly pass nondiscrimination bills as soon as H.B. 2 was repealed.

Christmas is also a time to celebrate faith, but by Wednesday, the only faith on hand was bad, with Charlotte distrustful of the General Assembly, and the General Assembly distrustful of Charlotte. Nonetheless, on Wednesday morning Charlotte’s city council met again and fully repealed the city’s ordinance, this time without a contingency clause.

By the time the General Assembly gaveled into session in Raleigh, tempers were high and hopes were sinking. It took quite some time for anyone to introduce a bill to actually repeal H.B. 2. A Republican legislator argued, apparently with a straight face, that the whole special session was unconstitutional, since they could just put the whole thing off until next month. He wasn’t wrong, but it was exactly the same argument that Democrats had made to object to the special session stripping Cooper’s powers last week.

Finally, Democrats introduced a simple bill that repealed H.B. 2. Republicans, with their large majority, ignored it and filed their own bill, which repealed H.B. 2 but also created a “cooling-off” period in which cities would not be allowed to pass any new ordinances on employment activities or public shower and bathroom accommodations.

Democrats were furious, saying the moratorium was a violation of the original deal, which was full repeal. What was even the point of repealing the law if cities still couldn’t pass the ordinances they wanted to? Debate on the Senate floor devolved into ad-hominem attacks. It started to appear that even with the moratorium, Republicans didn’t have the votes to pass the repeal. After all, many GOP members of the legislature still think H.B. 2 was a good idea.

Just before 7 p.m., Berger offered a last-ditch idea: He’d divide the bill into two parts, with separate votes on repeal and on the cooling-off period. But the senate soundly rejected the repeal part. That was the end of the road. The senate couldn’t pass anything, and the house adjourned without even voting.

It’s unclear what happens now. While some of North Carolina’s political embarrassments over the last year—from passing H.B. 2 to the stripping of gubernatorial powers—are clearly Republican affairs, Wednesday’s acrimonious saga ends with everyone looking bad. Cooper now limps toward his governorship looking weaker after his big push fell apart. The state remains saddled with a law that is unpopular with voters, economically costly, and nationally embarrassing. The failed special session will likely poison the well in any repeal attempt going forward. Perhaps Charlotte, bitter over the General Assembly reneging, will decide to re-enact its ordinance, even if it’s still superseded by state law.

This year in North Carolina politics has been especially cringeworthy: In addition to H.B. 2, there were federal court rulings that deemed a state voting law blatantly racist and a state redistricting plan unconstitutional; political rallies where protesters were punched; a bitter governor’s race that dragged on for nearly a month of pointless recounts; and then the special session to undermine Cooper. It only seems fitting that the state’s politicians should manage to squeeze in a final embarrassing fiasco before the year ended. There are still 10 days left, though, so there might be time for one more.

David A. Graham is a staff writer at The Atlantic, where this article was originally published.

NEXT STORY: New Evidence Says U.S. Sex-Offender Policies Are Actually Causing More Crime