Draining More Than 1,000 Swamps in D.C. and Beyond the Beltway

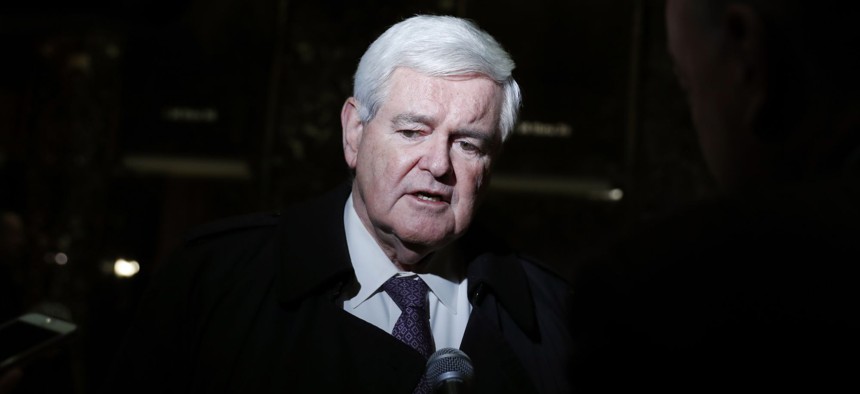

Former House Speaker Newt Gingrich speaks to the media at Trump Tower, Monday, Nov. 21, 2016 in New York. Carolyn Kaster / AP Photo

Connecting state and local government leaders

Newt Gingrich sees an era of ‘extraordinary decentralization’ as regulatory reformers set their sights on 50 state capitals and 1,000 city halls and county seats.

WASHINGTON — As the last speaker in a long morning of presentations on regulatory reform on Wednesday, former U.S. House Speaker Newt Gingrich could hardly be expected to add yet another modest proposal on taming the federal bureaucracy.

So it was not a surprise when Gingrich, always attracted to the truly big and incendiary idea, addressed the conference on a higher plane. The meeting at Covington & Burling LLP’s Washington, D.C., offices was titled “Drain the Swamp? Regulatory Reform Under President Trump.” Gingrich took it up a step, predicting policies that would radically decentralize decision-making toward lower levels of government while at the same time drastically shrinking the federal bureaucracy.

Gingrich’s five-minute talk, a blend of of his own ideas and a few predictions about the tone of the incoming team, was hyperbolically provocative—and perhaps prescient about the Trump’s approach to governing.

He began by observing that the Cabinet has fewer lawyers than any in recent memory. Its members are used to “hiring lawyers to find a way to yes,” he said, in contrast to “government lawyers whose job is to explain why it won’t be possible.”

The choice of Gen. James Mattis as Defense secretary, for instance, could not be done without a “waiver” of a law preventing such an appointment for seven years after conclusion of military service. “So you waive the law,” he said. “Trump understands that. His whole career was built on waiving the law—sometimes county law, sometimes city laws, sometimes zoning board regulations.”

Trump, Gingrich said, “is a roll-out quarterback who throws deep. If you’re that kind of a player, you’re going to throw interceptions. But he’ll get a lot more touchdowns than interceptions.”

Gingrich said the Pentagon was built in the “days of typewriters and carbon paper” and remained in that mindset even as communications technologies have advanced. He said “a minimum, conservative goal should be to reduce the Pentagon to a triangle, shrink it by 40 percent.”

The former House Speaker and current Trump confidant made this prognostication:

The great crisis of the Trump administration will be about 90 days in—when they will have a meeting of the Cabinet and will realize that in fact that the bureaucracy is massively denser than we thought it was and its capacity to resist us is massively denser than we thought it was. And there we will have two Marine four-star generals, a series of CEOs who are used to winning, the longest-serving governor in history of Texas, a Senator, a world-class neurosurgeon and they are going to say, ‘Okay, are they going to beat us or are we going to taken them apart? There will be no choice.’”

Speaking of regulation and management of federal programs, Gingrich predicted “extraordinary decentralization” to achieve a 21st century model focused on “output not inputs.” “You will have just liberated the whole country to experiment,” he said, mentioning governors, mayors, counties, school boards and companies. The new model, Gingrich added, “allows us to decentralize without abdicating” key federal responsibilities.

A Lot of Ideas

With 20 other speakers on the three-hour agenda, it was inevitable that, as one participant put it, that the conference as a whole seemed “a mile wide and an inch deep.” Nonetheless, its organizers—Common Good and Covington—attracted a roster of speakers whose knowledge of the topic was extensive, and whose ideas, if offered in only five minutes, were backed up by experience and research.

The first speaker was a swamp-dweller who might be a candidate for draining--were he not in a key regulatory reform post. He was Richard G. Kidd IV, the chairman of the new Federal Permitting Improvement Steering Council. Kidd described the substantial agenda of regulatory reform that was included in last year’s FAST Act—an agenda that has extended permitting improvement processes pioneered by the U.S. Department of Transportation to many other federal agencies. The council’s background and work was detailed in this Route Fifty article published last month.

Kidd views his position as that of an advocate in the White House for permitting improvement, and he said the new president should commit both to the position and to spending $30 million to capitalize a permitting improvement fund authorized by the FAST Act. The law gives deputy secretaries of the departments responsibilities for permitting improvement, and Kidd said that Trump should hold them accountable for these duties. But he emphasized that federal permitting work is concentrated in the bowels of many agencies and he advocated better training for those who do it.

Criticism of federal procedures was voiced by E. Donald Elliott, a Covington partner who also teaches at Yale Law School. Getting important projects rolling is a priority for governors in the 50 states, he said, but agencies like the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission take a more lackadaisical view, waiting to start their processes until the states have signed off. And, of course, multiple federal agencies often need to approve projects, a problem that has engendered continuing calls for appointment of a “lead” agency for each project from reformers such as Philip K. Howard, founder of Common Good, a sponsor of yesterday’s event. Elliott advanced the improbable idea that the 7,000 members of the federal Senior Executive Service should be limited to 6-year terms subject to confirmation, or firing, by Congress.

Christopher DeMuth, for many years president of the American Enterprise Institute and now a fellow at the Hudson Institute, was among several speakers who called for a larger role for Congress in approving key regulations. Last August, a bipartisan majority in the House passed the Regulations From the Executive in Need of Scrutiny Act of 2015 (the REINS Act). It would require any regulation with an annual economic impact of $100 million or more to come before Congress for an up-or-down vote before taking effect. This should be enacted, DeMuth said, but he observed that it would not address the problem of very old statutes that need updating. Among them is the Clean Air Act, which has not been amended in the past 26 years.

Congressional capability for review of regulations has diminished thanks to heavy turnover among members and staff in recent years. So several of the experts at the Common Good gathering advocated creation of a new institution, analogous to the Congressional Budget Office, to give the legislative branch the expertise to oversee the regulatory state. Phillip A. Wallach of the Brookings Institution, would call it the Congressional Regulation Office, while Susan Dudley of George Washington University proposed an Office of Regulatory Review and Analysis. Wallach’s paper on the issue was published in National Affairs this fall.

At the same time, the regulatory review capability of the White House has diminished, as the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, part of the Office of Management and Budget, has atrophied in recent years. Its staff, close to 100 after its creation in 1980, now has only about 50 members, while the number of regulatory staff in federal agencies has exploded from 146,000 in 1980 to 278,00 in 2016, according to Paul Noe, who oversaw regulatory agencies on Congressional staffs before joining the American Forest and Paper Association, a speaker at the event. Several speakers said OIRA’s staff should be substantially enlarged.

Thousands of Swamps to Drain?

While much of the conference focused on federal regulation, one speaker in particular called out state and local regulatory obstacles to economic growth.

Brink Lindsey of the libertarian Cato Institute asserted that “there are 50 other swamps—and 1,000 more swamps at the municipal level—silent killers of growth that are off the media grid.” Zoning regulations that have impeded housing development, particularly in coastal urban centers, are one obvious example. Resulting high prices of renting or owning have kept talented people away from these centers of creativity—shaving perhaps 10 percent from the nation’s potential economic output, Lindsey said. States’ licensing of occupations is another economic retardant, he observed, since it drives up the cost of many services—medical care, haircutting, beekeeping included. In 1970, 10 percent of occupations required licensing. Today, the share is 30 percent.

Federal action could preempt anticompetitive state licensing practices, Lindsey suggested. And the federal government could also offer financial incentives to encourage big cities and their suburbs to loosen zoning restrictions so as to encourage creation of more housing units.

Excitement About Change

These and other ideas stand a better chance of serious consideration, many at the conference believed. “It’s an exciting time,” said Philip Howard as he closed the meeting.

And perhaps we are, as Gingrich argued, at a “watershed moment” in the history of the American public sector.

Timothy B. Clark is Editor at Large at Government Executive's Route Fifty.

NEXT STORY: Case Study: How Norfolk Streamlined Construction Management