In Tide of Red Ink, Some States Show Surpluses

The Georgia State Capitol.

Connecting state and local government leaders

The budget winners avoided deep tax cuts and maintained robust rainy day funds.

This article was originally published at Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, and was written by Elaine S. Povich.

It’s shaping up to be a tough financial year for many states. At least 30 of them have budget shortfalls, and President Donald Trump’s promises to scrap the Affordable Care Act and overhaul the federal tax code have created fiscal uncertainty.

But whatever happens in Washington, some states will be well positioned to deal with it without raising taxes or making deep spending cuts.

California, Georgia, Idaho and Utah are among the states that have put themselves on a solid fiscal footing by avoiding deep tax cuts, enacting targeted tax increases, and diverting some surplus money into “rainy day” funds to be tapped in leaner times.

By taking those steps, and by forgoing the temptation to rely on a single revenue source, those states are in good financial shape heading into this year’s legislative sessions. Their strategies may be instructive for other states.

Elizabeth McNichol, a senior fellow at the left-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, said the key is “to plan ahead and have a rainy day fund, specifically tied to the volatility of your specific tax system.”

McNichol pointed to states like California and Massachusetts, which mandate that if a budget surplus is large enough, a portion of it must be added to the state’s rainy day fund. And it helps to be cautious in projecting how the economy will perform, the amount of revenue that will come in, and what the state will be able to afford to spend.

In California, for instance, Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown is proposing increasing his state’s rainy day fund to $7.9 billion from $6.7 billion, even though he projects a $1.6 billion shortfall in his proposed $179.5 billion budget. Instead of tapping reserves to close the gap, Brown wants to slow school spending growth and roll back a series of one-time expenses.

A cautious Brown is expecting a $5.8 billion downturn in revenue growth. And he’s bracing for the possibility that Trump and the Republican majority in Congress will cut federal income taxes deeply and scrap the Affordable Care Act.

“We can’t budget something that hasn’t happened yet,” Brown told reporters. “That’s why we have to hang on to our hat here.”

Another step states can take to avoid a budget crisis is to not cut taxes too deeply even when it appears economic times are good or getting better.

Take Georgia, for instance. It has a surplus. That’s partly because Georgia’s economy is growing faster than much of the rest of the nation.

But Georgia also resisted cutting taxes in recent years, while modestly projecting revenue and diverting excess amounts into the state’s rainy day fund, said Wesley Tharpe, research director at the progressive Georgia Budget and Policy Institute.

As a result, Republican Gov. Nathan Deal is proposing a record $25 billion budget for next year that is based on projected revenue growth of 3.6 percent. The budget calls for increases in spending for law enforcement personnel and educators, a couple of big-ticket infrastructure projects — and no tax increases.

“Even though no one enjoys paying taxes, the state does need a certain amount of revenue to meet the challenges” of education and transportation, Tharpe said.

In contrast, Kansas has faced recurring budget shortfalls after cutting income taxes in 2012 and 2013. Now Republican Gov. Sam Brownback is proposing increasing some excise taxes and scraping other funds, such as transportation, to cover a projected $342 million shortfall in its current budget and gaps in funding for existing programs totaling $1.1 billion through June 2019.

Shortfalls Predominate

According to MultiState Associates Inc., a lobbying firm that closely tracks state issues, at least 31 states are facing budget shortfalls in their current budgets. The gaps will have to be addressed at the same time that legislatures draft budgets for the next fiscal year or two.

The National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO) said tax revenue that finances states’ general funds slowed considerably in fiscal 2016, increasing just 1.8 percent overall. A dozen states saw a decline in revenue, 30 states saw growth up to 5 percent, and seven states had growth between 5 and 10 percent. Just one, Nevada, had growth above 10 percent.

NASBO estimates that revenue in fiscal 2017 will come in below projections in 24 states, on target in 16 states, and above forecast in only four states.

State finances are often buffeted by national and global economic conditions. Farm states and oil- and gas-producing states, for example, have been dented by the global drop in commodity prices. When oil and gas drilling slows or crop prices drop, the resulting job losses, lower income and less consumer spending translate into less tax revenue for states.

But the economies of other states, including California, Georgia, Idaho and Utah, have rebounded from the recession and weathered other fluctuations in the economy.

States’ economic conditions vary widely, said John Hicks, NASBO’s executive director.

“There are states in the West and the mid-Atlantic that are doing well. Their employment is up and their income is up,” he said. “Then there are states that have had continued fiscal stress. Should revenue shortfalls hit them on top of past difficulties, they are in a more difficult situation to resolve.”

Back-to-back years of weak economic growth also can affect states’ ability to sock away reserves in rainy day funds. Instead, they find themselves tapping them to make up for revenue shortfalls.

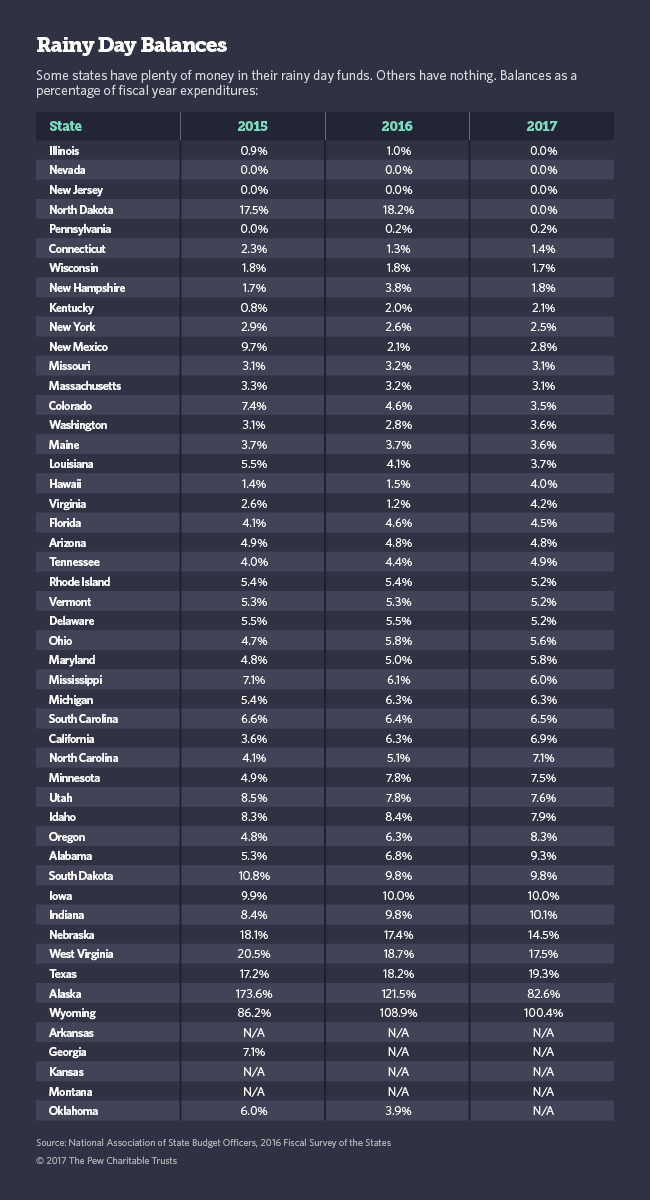

NASBO reports that 25 states project increases in their rainy day fund balances this year compared to 29 last year and 31 the year before that.

Some states, such as Alaska, are heavily dependent on severance tax revenue and depleted their rainy day funds during that time. This year, however, Alaska plans to stash more per capita than any other state.

States can take other steps to immunize themselves against the fluctuations of a national or global economy — such as diversifying their tax base so they aren’t too dependent on any one tax, such as an energy tax on oil and gas extraction or an income tax on capital gains, which usually is paid by high-income taxpayers, but is subject to the vagaries of the stock market.

“If you tax capital gains, when the stock market goes up that’s good, but when it goes down, it’s not so good,” said McNichol of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

She said states also can help themselves stay in the black by using extra revenue they have during flush times on one-time expenditures, such as repairs to infrastructure — rather than on ongoing government expenses.

It also helps to try to adapt to a changing economy. In the face of declining sales tax receipts caused by Americans shopping more online instead of in brick-and-mortar stores, some states are looking to adapt by taxing online sales, and by broadening the sales tax to apply to services like haircuts or even video streaming. But some of those taxes aren’t in place yet and their revenue may not make up all the revenue that is lost.

Demands on Surpluses

Utah is a low-tax state, whose economy has been growing and is expected to continue growing. It forecasts a budget increase of nearly $74 million.

Phil Dean, Utah’s state budget director and chief economist, said the state has a long-standing “culture of prudent fiscal management” that includes reassessing the condition of its rainy day fund every year.

The reassessment also includes what he calls “budget stress-testing,” which involves studying what effect various economic scenarios, such as a recession, would have on the state’s budget. Last year, he said, the state modeled three scenarios: a five-year forecast, a two-year forecast and a “stagflation” (recession coupled with inflation) forecast, and has budgeted accordingly.

Having the luxury of a surplus not only allows states to avoid the political pitfalls of having to raise taxes or cut spending on some services taxpayers may want, it allows them to address the needs they see.

However, it also increases the clamor to spend.

In Utah, the business community is pressuring Herbert and lawmakers to spend more on K-12 and post-secondary education because businesses locating to Utah increasingly need an educated workforce, according to Tim Chambless, professor at the University of Utah’s nonpartisan Hinckley Institute of Politics.

And when there’s a surplus, there’s always pressure to cut taxes rather than spend it on what others perceive as a need for more or better public services, including education.

Take nearby Idaho, another low-tax, black-ink state, which forecasts a surplus of $130.8 million.

Republican Gov. C. L. “Butch” Otter is proposing a 5.9 percent general fund spending increase for next year and wants to spend an extra $58 million to increase teachers’ pay to improve his state’s public education system. Some lawmakers, however, want to return much of the surplus to taxpayers in the form of tax cuts.

However, a poll by Boise State University released this month showed that 46 percent of those surveyed said the surplus should go to education, with only 9 percent favoring a tax cut. Some 24 percent wanted the surplus to go into the rainy day account, and 17 percent called for investments in roads and bridges.

“It’s fair to say that Idahoans are aware that schools have been cut and that’s something they value highly,” said Lauren Necochea, director of the centrist think tank Idaho Center for Fiscal Policy. “I don’t think anyone in Idaho wants to pay more taxes than necessary for good education. But they understand we are not where we want to be.”

NEXT STORY: ‘Zika Isn’t Gone, It’s Sleeping’