Even Healthy-Looking Suburbs Are Dying From Drugs

Shutterstock

Some communities are much sicker than they look, according to an analysis of CDC data and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s new county health rankings.

Full of historic suburban towns on Boston’s outskirts, Essex County, Massachusetts, does not look sick on paper. It is not plagued by obesity, diabetes, or heart disease. Folks get a fair amount of exercise. Most are insured. Judging by social factors that influence health, it should actually be in better-than-average shape: Nearly 38 percent of the population is college-educated. Only 11 percent live in poverty.

Yet all is not well in Essex County. Drugs are claiming lives at a growing rate. In 2010, drugs were responsible for the deaths of roughly 11 out of 100,000 people countywide—a rate that nearly tripled to 31 by 2015, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Essex County’s lethal spike—driven by heroin and prescription painkillers—speaks to a national opioid addiction that’s been growing for years. It is also a poster child for the emerging geographic dimension of this crisis: Larger, suburban counties outside of major metros—in some cases, places that “should” be healthy by other standards—are where drugs are claiming the most lives.

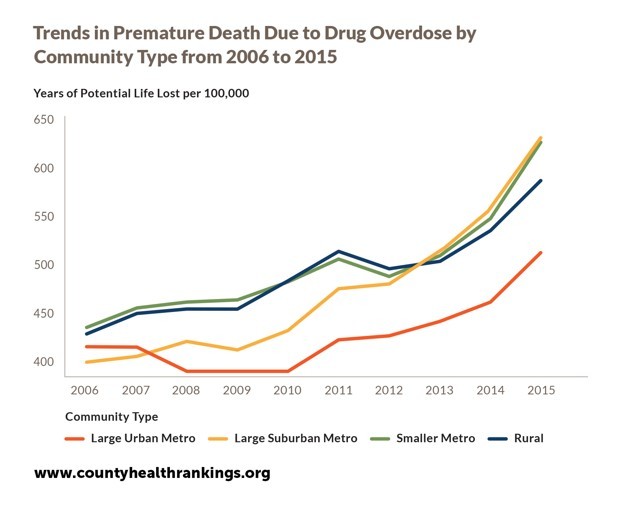

Released Wednesday, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s 2017 County Health Rankings and an accompanying report analyze county-level data from all 50 states on more than 30 public health outcomes and behaviors. The report finds there’s been a clear flip in the geography of addiction: One decade ago, large suburban areas experienced the lowest rates of premature deaths due to drug overdoses. In 2015, they had the highest.

The Johnson Foundation’s analysis doesn’t pinpoint which counties experienced the most dramatic gains in drug-induced death. What it does is rank every county in the U.S., by state, using data that reflects local health conditions, such as diabetes and obesity, as well as measures that can predict health outcomes, including teen birth, smoking rates, and grocery store access.

Some composite information about drug-related deaths is included in the Johnson Foundations’ county “report cards,” but it’s not factored into each county’s overall ranking. To understand the kinds of suburbs experiencing spikes in overdoses, I analyzed CDC mortality data online.

Comparing those numbers to the Johnson Foundation report, I found startling disconnects between deadly drug problems and places that have an otherwise fairly “healthy” facade. For example, Essex County ranks sixth out of the 14 counties in the Bay State by the new report—middle-of-the-road when it comes to the chronic health conditions that normally wave red flags for public health researchers. Yet it’s increasingly afflicted by drug-related deaths.

On the fringes of Cincinnati, Boone County, Kentucky, ranks first out of 120 across its state on all other health rankings. As in Essex County, rates of diabetes, smoking, and teen births are relatively low; poverty is suppressed, and employment is solid. Yet a look at CDC data shows county saw its drug-related death rate leap from 26 in 2010 to nearly 46 in 2015. Ranked smack in the middle of Ohio’s 88 counties and also included in the Cincinnati metro area, Clermont County saw a similar leap. Another example: Clay County, part of the Jacksonville, Florida, metro area, is 11th of the Sunshine State’s 67 counties. But drug-related deaths increased from 14 in 2010 to 23 in 2015.

Some suburbs appear to making improvements: for example, Paulding County, Georgia, on the edges of Atlanta, saw its yearly rate drop from roughly 27 to 16 from 2010 to 2015.

That said, the Johnson Foundation report states that premature deaths related to drug overdoses rose across all community types—suburban, urban, and rural. Though healthy-looking counties are watching opioids claim an alarming number of too-young lives, the very highest rates are still found in some of the poorest, sickest parts of the country. In 2015, McDowell County, West Virginia, experienced a narcotics-induced death rate of 141—just about the highest in the nation. It also clocked in last out of the Mountain State’s rankings. (West Virginia has been ground zero in the nation’s opioid epidemic, largely due to a tragic confluence of economic factors.)

Drug mortality rates are notoriously shifty; according to the CDC, they’re likely undercounted in many counties, due to unresolved cases and misclassification. But the national trend is clear: Americans are dying too young from addiction—even in communities that otherwise appear healthy.

Laura Bliss is a staff writer for CityLab where this article was originally published.

NEXT STORY: N.M. Ranch Owner on Mexico Border Has Tough Message for Trump