Trump Budget Plan Calls for States to Pay About 25% of Food Stamp Benefits by 2023

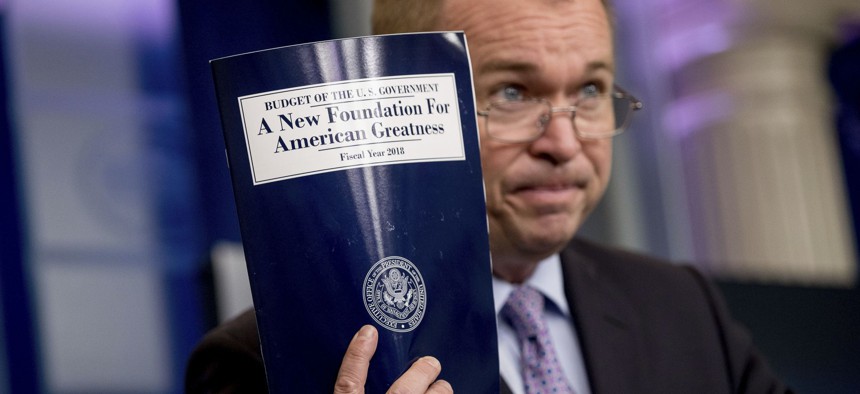

Budget Director Mick Mulvaney holds up a copy of President Donald Trump's proposed fiscal 2018 federal budget. Andrew Harnik / AP Photo

Connecting state and local government leaders

A cost-sharing arrangement the administration has proposed would mark a major financial restructuring of the SNAP program, which covered $66 billion in benefits last year.

WASHINGTON — President Trump’s budget proposal would dramatically alter the way states and the federal government divvy up the cost of providing food stamp benefits to low-income Americans in the years ahead.

The proposed shift would confront states with significant new costs at a time when some of them are already facing financial pressure. And there are worries that the president’s plan, if enacted, could lead to poor households losing access to assistance they use to buy groceries.

Currently, the federal government pays all of the benefit costs for the food stamp program, known formally as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP.

But the White House spending plan for fiscal year 2018 released on Tuesday calls for state governments to pitch in matching funds. The phased-in state match would start at a national average of 10 percent in 2020 and rise to an average of 25 percent in 2023.

Trump’s budget estimates that the matching program along with other changes to SNAP would lead to nearly $191 billion in federal savings over a decade.

Food stamp benefits cost about $66 billion during 2016.

A 10 percent share of that total would have been about $6.6 billion.

"States in general are having tight margins right now,” John Hicks, the executive director of the National Association of State Budget Officers, said by phone on Tuesday. “If you're talking about something on the order of $7 billion, generally, as a new obligation, that's a real number.”

Trump’s budget says that the match program would rely on a formula that incorporates economic indicators to determine the share of SNAP benefits that individual states would contribute.

States do currently pay a portion of the administrative costs for SNAP. But these costs are minor compared to the bill the federal government foots for benefits. The administrative costs fall into a category of expenses that totalled about $4.3 billion last year.

Melissa Boteach, vice president of the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center for American Progress, a liberal advocacy group, criticized the proposed cost sharing arrangement for benefits.

“This is a big deal and it will hurt a lot of struggling families,” she said.

An average of about 44 million people participated in the SNAP program each month during 2016.

“When you shift costs to states in that way, in some cases they won’t step up and in other cases they may step up there, but end up cutting other funding,” Boteach said.

The White House budget plan notes that the food stamp cost-sharing proposal would allow states “to determine their level of SNAP benefits” and that “it is fairly and reasonably designed and gives States options that can mitigate the effects of the funding shift.”

Boteach said a Center for American Progress analysis found that the Trump plan could lead to eight million households losing SNAP benefits over the coming decade.

White House Budget Director Mick Mulvaney said on Monday that the proposed cost-sharing arrangement was meant to set up a dynamic where states have some “skin in the game.”

The administration is also seeking to tighten work requirements for the food stamp program for able-bodied adults without children.

“Look, if there’s 44 million people on there, eight years from the end of the recession, maybe, maybe it's reasonable to ask if there are folks who are on there who shouldn’t be,” Mulvaney said at a press briefing on Tuesday, referring to the Great Recession.

“That is a reasonable question to ask,” he added. “I would even suggest to you it's a compassionate question to ask.”

In 2007, the number of monthly SNAP participants averaged around 26 million. But, since 2010, the figure has hovered between 40 million and 48 million.

“Part of this is that corporations are not paying their workers enough to afford food,” Boteach said. “People are turning to SNAP because their wages are too low, or because they’re searching for work, or because they’re a child, or a person with a disability, or a senior.”

From a state budget perspective, some of the factors currently posing challenges include sluggish tax revenues, pension costs for retired public workers and maintaining school systems. Low oil and natural gas prices are added difficulties in states with economies closely linked to those commodities.

Hicks was not aware of any robust dialogue between the Trump administration and state officials about the prospect of transitioning to the state match program for SNAP.

“That’s why I would say this is going to be a surprise to states,” he said. “It wasn't preceded with a notable set of conversations.”

Bill Lucia is a Senior Reporter for Government Executive’s Route Fifty and is based in Washington, D.C.

NEXT STORY: Sanctuary Cities an Afterthought Among DOJ Priorities in Trump Budget Proposal