As Surrogacy Surges, New Parents Seek Legal Protections

Connecting state and local government leaders

As more couples turn to surrogates to carry their child, some states are considering further protections for the intended parents, many of whom are gay, by handling custody issues before a child is born.

This article was originally published at Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, and was written by Rebecca Beitsch.

When Brad Hoylman and his husband wanted to start a family, they looked to a woman nearly 3,000 miles away to carry their child.

The two Manhattanites turned to a surrogate in California, a state with a robust commercial surrogacy industry, because the practice is banned in New York.

The advent of gay marriage, advances in reproductive technology, and the fact that more people are waiting longer to start families have fueled a surge in the surrogacy industry.

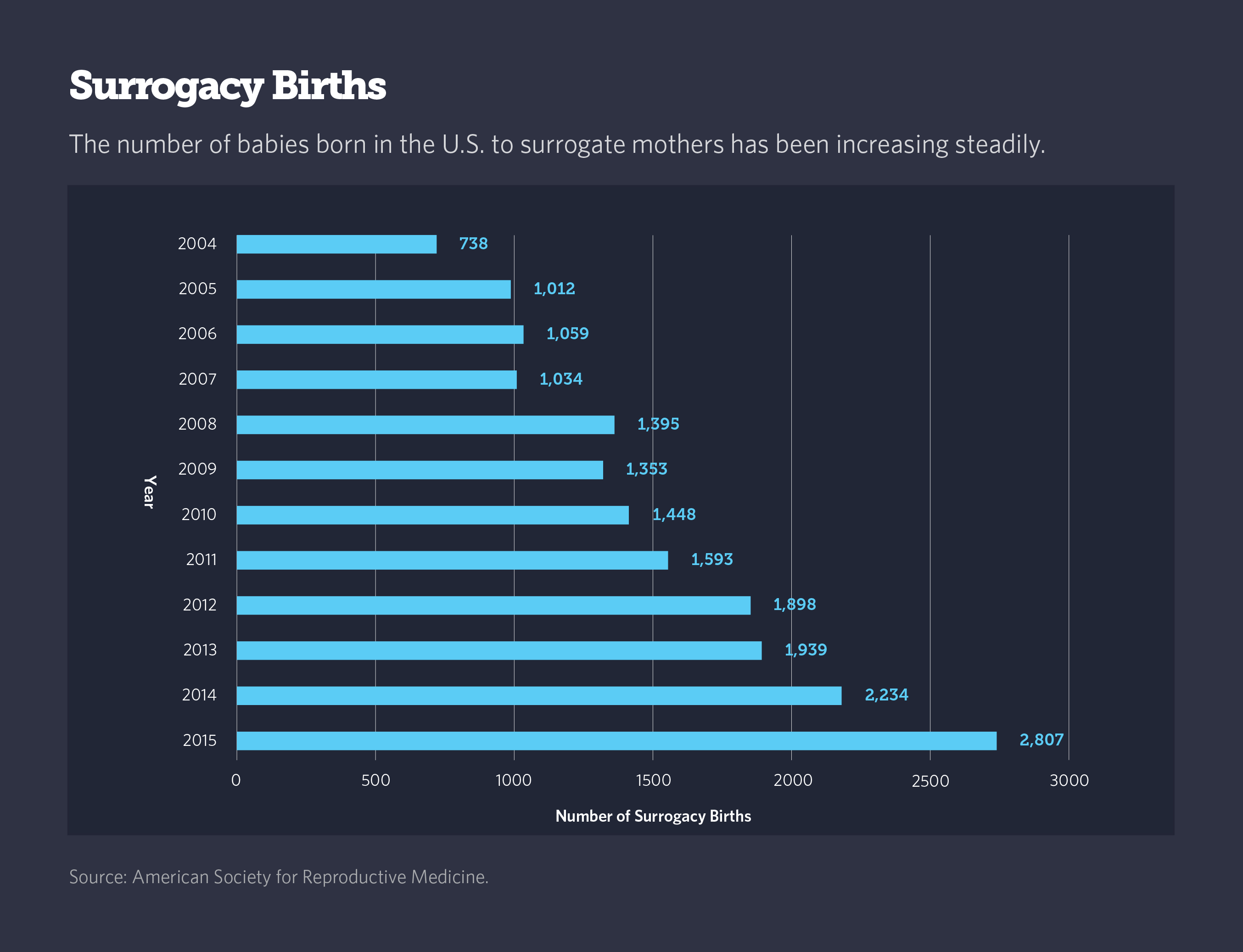

In 2015, 2,807 babies were born through surrogacy in the U.S., up from 738 in 2004, according to the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Women are often paid at least $30,000 to carry a baby created from the egg and sperm of others.

But in many places, once the baby arrives, outdated state laws fail to answer an important question: Who are the parents?

In many states the law is murky or even silent on surrogacy. The industry is free to operate but the contracts signed between surrogates and intended parents may not be legally binding. The baby may be born in a state that views the woman who gave birth as its mother, even if she has no genetic connection to the child.

The legal uncertainty is particularly concerning to the intended parents, who usually spend about $100,000 (including payments to a surrogate and the company she works with as well as doctors and lawyers) and risk ending up without the child they counted on. Gay male couples have an additional fear: that they might be discriminated against if they are embroiled in a legal fight over custody.

In states that ban commercial surrogacy and those with no laws at all, legislators are pushing bills that would legalize the practice, determine parentage before a child arrives, and ensure that contracts are enforceable and followed by all parties. In many cases, they would require surrogates to be at least 21, to have already given birth to their own children, and to undergo medical and psychiatric evaluations before signing a contract.

Hoylman, a state senator from New York, introduced a bill this year that would legalize surrogacy in his state and establish the legal framework of intended parentage.

Surrogacy became legal in Washington, D.C., in April, and lawmakers in Minnesota and Massachusetts debated bills this year but didn’t approve them. In New Jersey, state lawmakers passed similar bills in 2012 and in 2015, but Republican Gov. Chris Christie vetoed them. The Senate passed another bill this week.

Women and Babies as Commodities?

Critics of surrogacy, including both religious conservatives and some feminists, object to what they view as the commodification of both women and children. Opponents point to numerous European countries that have banned the practice and say states should be wary of letting American women be used by others, including foreigners searching for surrogates beyond their borders.

For many, the financial aspect of surrogacy is most troubling.

“Women will be exploited by wealthy people,” said Jason Adkins, executive director of Minnesota’s Catholic Conference. “We see all kinds of Hollywood stars contracting with surrogates, but we don’t see any Hollywood stars serving as surrogates for their nannies and maids.”

Surrogacy companies prefer to work with women they consider financially stable in order to avoid women who may be acting out of financial desperation. Medicaid does not cover surrogacy costs, and women who are enrolled in the program would risk losing coverage for themselves and their families if they carry a surrogate baby.

Hoylman, and even some surrogacy critics, say having no rules puts surrogates and intended parents at risk.

Two married men in Virginia nearly lost their child who was born through a surrogate in Wisconsin after a judge there declared the baby an orphan rather than turn it over to either the parents or the surrogate. The couple later won custody, and the judge resigned.

Hoylman and his husband turned to a surrogate in California six years ago to avoid such trouble. They plan to return to the state in August for the birth of their second child.

In California, and in most of the other 11 states and Washington, D.C., that permit commercial surrogacy, the intended parents are able to get pre-birth orders that name them as parents before a child even arrives.

Only Indiana, Nebraska, New Jersey, Michigan and Washington share New York’s ban on commercial surrogacy. By lifting the ban, Hoylman hopes New Yorkers would no longer be forced to go to nearby states, where their parental rights may not be recognized.

“I don’t want to send New Yorkers to other states especially where laws aren’t even written. It’s dangerous. I can picture the image of a judge in some rural part of the country, on the bench, looking down his nose at a gay couple and their surrogate and trying to determine just who the parent of this child is,” he said. “That’s my worst-case scenario.”

The Supreme Court’s 2015 decision to allow same-sex marriage in all 50 states has further opened the door to surrogacy for gay couples, as five states allow the process only for married couples. But not all have created a welcoming environment for gay couples: Louisiana limits surrogacy to heterosexual couples by requiring that the intended parents supply both the sperm and egg used in the process.

Multiple Steps in Minnesota

Minnesota has no laws on the books governing surrogacy, yet it has a robust industry. A number of surrogacy companies in the state match women with couples who are frequently gay and often come from countries where surrogacy is prohibited.

Because the state has no laws on the books governing surrogacy, couples often go through a multistep process to obtain custody, said Steve Snyder, a lawyer who owns a surrogacy company and represents intended parents in court. The process is especially fraught for gay male couples who fear they may not get the necessary judicial approval.

If a surrogate is married, Minnesota law presumes her husband to be the father of the child. In the case of two gay men, the genetic father must file a paternity suit to remove the surrogate’s husband from the child’s birth certificate. The surrogate and genetic father are then listed as the child’s parents. Once the surrogate waives her parental rights, the genetic father’s spouse is free to adopt the child.

Surrogates who work with Snyder’s agency sign a contract saying they will not visit Michigan, New York, Nebraska, New Jersey or Washington during the pregnancy for fear that if they delivered there, it could be difficult to transfer custody to the intended parents.

State Rep. John Lesch, a Democrat who sponsored legislation that would allow commercial surrogacy and establish the process to obtain a pre-birth order, said Minnesota’s current process leaves gay couples facing too much risk that they will be discriminated against during the legal process. He doesn’t want parents fighting judges for custody like the couple in Wisconsin.

“Very few parents are going to want to enter into a legal minefield with knowing most judges are pretty good,” he said. “They’re going to want to know the law is on their side.”

Famous cases like the 1988 “Baby M” case, in which a New Jersey surrogate attempted to keep the baby she delivered, helped spur bans on surrogacy in that state and others. But such instances are quite rare, Snyder said, and proponents of surrogacy laws seem to be more worried about what actions judges or intended parents might take.

Pre-birth orders would solve the problem of disputed parentage. Because the contracts would be enforceable, surrogates would be required to give up the child and the new parents would be required to take it.

Many surrogates say they want legal protection to ensure the intended parents take the baby, regardless of any birth defects or a change in their own life situations.

“Both sides are taking an emotional risk. We’re taking on more of a physical risk; [intended parents] are taking on more of a financial and legal risk,” said Traci Woolard, 44, a Minnesota woman who has delivered five babies as a surrogate after having four children of her own.

Woolard’s fear is that a judge could decide to leave her with a baby. “My family’s done. It’s complete, and I do not want to have any more children.”

NEXT STORY: U.S. House Committee OKs Brownfields Legislation