While Most Small Towns Languish, Some Flourish

Connecting state and local government leaders

Small towns in some Western and Southern states are booming, as fast-growing metro areas start to swallow up outlying towns.

This article was originally published at Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, and was written by Tim Henderson.

By now, the demise of the American small town is a common tale. But even as most of them continue to lose residents, a few are adding them at a rapid clip.

In several Western and Southern states, small towns are growing quickly as fast-growing metro areas swallow up more outlying towns, according to a Stateline analysis of census estimates.

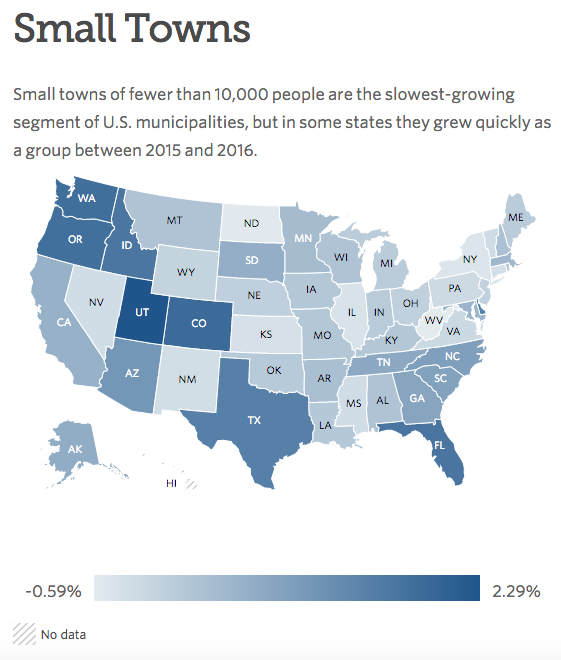

Between 2015 and 2016, the growth was particularly strong in small towns in Utah, Colorado, Washington, Oregon, Florida, Idaho, Delaware, Texas, Arizona, North Carolina and South Carolina, where small towns grew around 1 percent or more.

During the same period, 54 percent of small towns across the U.S. lost population, and most others saw only limited growth. (For purposes of the analysis, Stateline defined “small towns” as those having fewer than 10,000 residents, a common standard.)

Copyright © 1996-2017 The Pew Charitable Trusts. All rights reserved.

The analysis shows there’s no single way of looking at the fate of small-town America, said Brookings Institution demographer William Frey. “It seems to be tied to the economic and demographic success, or lack thereof, of the larger region,” he said.

The reasons for growth can be varied, according to Frey and other demographers. Jobs in booming cities can draw new residents to nearby small towns, where quiet streets and good schools can be especially appealing to millennials ready to raise children. In some states, urban gentrification has pushed the poor and immigrants further into outlying towns, where housing is less expensive.

The growth may portend a renewed interest in faraway suburbs, which was tamped down during the recession, Frey said.

“The more successful parts of the country may be poised to experience a renewed ‘exurbanization’ as the economy picks up,” Frey said, referring to people who choose to live in rural areas while commuting into the city for work. The trend could lead to continued growth of small towns in states like Colorado, Oregon and Utah.

Small Towns Shine

Some of the fastest-growing small towns are being swallowed up by surrounding metro areas. Among them: the former farming community of Vineyard, Utah, where a massive new housing and retail development fed by new highways has pushed the population from 139 in 2010 to almost 4,000 last year.

Vineyard is part of a rapidly growing area between Provo and Salt Lake City that demographer Pamela Perlich of the University of Utah compared to “twin cities” like Dallas and Fort Worth in Texas.

“The area between those two is the most rapidly growing in a rapidly growing state,” Perlich said.

Utah County, which includes Provo and Vineyard, gained jobs at the highest rate — about 5 percent — of any large county in the nation last year, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data. The area around Salt Lake City has earned the nickname “Silicon Slopes” for its combination of high-tech enterprises, including the nearby National Security Agency’s Utah Data Center, and ski resorts a short plane ride from California’s Silicon Valley.

Washington state, where the small-town population grew by almost 2 percent last year, trailing only Utah and Colorado, has seen more of its residents moving to outlying areas as a tech boom has driven up housing prices near Seattle.

“I would love to tell you that people love the quieter small-town lifestyle,” said Mayor Daryl Eidinger of Edgewood, a town 27 miles south of Seattle whose population grew 9 percent last year, from 9,810 to 10,734. “But I attribute our growth to the high cost of housing to the north of us, in Seattle,” Eidinger said, adding that he expects another 10 percent growth to be recorded this year. “It will never be as quiet as it was 20 years ago,” he added.

In some areas, gentrification is leading to a new small-town life for those seeking affordability and diversity.

Lincolnville, South Carolina, was founded after the Civil War by freed slaves looking for a respite from racial discrimination in nearby Charleston. Today it is now about half white and 40 percent black.

The town’s population grew by 700 last year, to 1,971, mostly because its borders expanded to include an apartment building with 320 units, Mayor Charles Duberry said. But it was growing before that, by about 6 percent between 2010 and 2015, as more people who grew up there bought land and built their own houses.

“When people come here they feel welcome, and that makes a big difference,” Duberry said. Many residents, including Duberry, work in local shipyards.

Partly because of the growth, the town is planning to bring back its local police department, which disbanded in 2012.

The small-town population in Texas grew by 30,791 last year, the biggest increase of any state. As in Utah, many of those small towns are “in the path of economic growth” near expanding cities, said Lloyd Potter, Texas’s state demographer.

“Those small towns are in the midst of fairly dramatic economic and population growth because they’re close to areas where a lot of jobs are being created,” said Potter.

The fastest growing small town in Texas is Fulshear, outside Houston, which has been growing by more than 1,000 residents annually since 2013 and now has almost 8,000 residents. The population of Dripping Springs, west of Austin, grew 26 percent last year, to 3,140.

But some northwestern parts of the state have generally been left out, with some small towns shrinking as aging residents move toward cities where their children now live, Potter said.

Scenic Beauty

Small-town population shrank in 16 states, with Illinois, New York and Pennsylvania each shedding more than 10,000 small-town residents. Small towns in New York lost 16,903 residents, making it the state with the largest decline.

Since 2010, the number of rural areas, including small towns, in the eastern U.S. that are shrinking has increased dramatically, said John Cromartie, a geographer for the U.S. Department of Agriculture who tracks changes in rural areas.

Some small towns in New York are bucking the trend and growing — either because they’re drawing affluent millennial commuters ready to have children in a leafy suburb, or because new immigrants and other low-skilled workers are fleeing gentrification, said E.J. McMahon, research director for the conservative Empire Center for Public Policy in New York.

Both groups accept longer commutes as the price of more affordable housing and better schools, said McMahon, who has written about recent declines in upstate rural population.

Some areas known for scenic beauty and recreation are also doing well, Cromartie said. He pointed to Waterford, New York, south of Saratoga Springs, which was the fastest-growing small town in New York last year, up 6 percent to 2,167 residents.

Scenic destinations like the Saratoga area were hit hard by the housing crisis and recession but showed a lot of improvement nationwide between 2015 and 2016, Cromartie said.

But even natural beauty is no guarantee of small-town success. Maurice River Township, New Jersey, has the Delaware Bay and its namesake river, but the town’s population has shrunk to less than 6,600 in 2016, down 7 percent from 2015 and 18 percent from 2010.

The town adopted an ordinance in April requiring owners of vacant houses to register and pay an escalating annual fee, which Mayor Patricia Gross said would cover some of the costs of decreased property values and extra maintenance.

NEXT STORY: New Ecological Disaster for Chesapeake Bay Watershed May Be Just 3 Years Away