The Looming Consequences of Breathing Mold

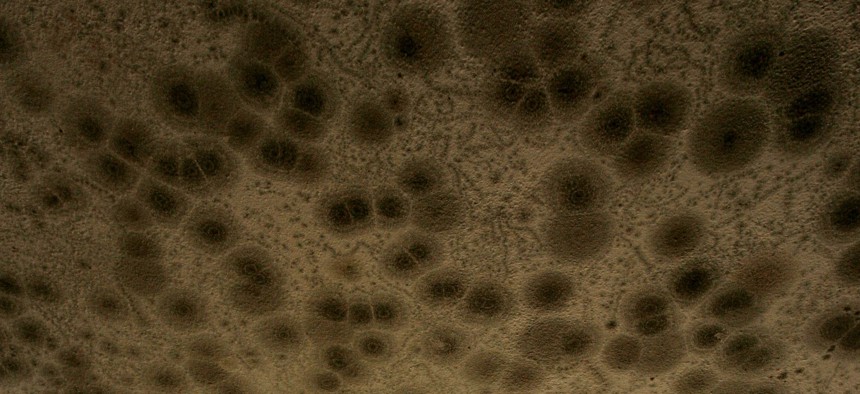

Don Ryan / AP File Photo Mold creates interesting patterns on the ceiling and walls of a flood damaged house in New Orleans, La., Saturday, Oct. 8, 2005.

Flooding means health issues that unfold for years.

The flooding of Houston is a health catastrophe unfolding publicly in slow motion. Much of the country is watching as 50 inches of water rise around the chairs of residents in nursing homes and submerge semitrucks. Some 20 trillion gallons of water are pouring onto the urban plain, where developers have paved over the wetlands that would drain the water.

The toll on human life and health so far has been small relative to what the images suggest. Authorities have cited thirty known deaths as of Tuesday night, while 13,000 people have been rescued. President Donald Trump—who this month undid an Obama-era requirement that infrastructure projects be constructed to endure rising sea levels—offered swift reassurance on Twitter: “Major rescue operations underway!” and “Spirit of the people is incredible. Thanks!”

But the impact of hurricanes on health is not captured in the mortality and morbidity numbers in the days after the rain. This is typified by the inglorious problem of mold.

Submerging a city means introducing a new ecosystem of fungal growth that will change the health of the population in ways we are only beginning to understand. The same infrastructure and geography that have kept this water from dissipating created a uniquely prolonged period for fungal overgrowth to take hold, which can mean health effects that will bear out over years and lifetimes.

The documented dangers of excessive mold exposure are many. Guidelines issued by the World Health Organization note that living or working amid mold is associated with respiratory symptoms, allergies, asthma, and immunological reactions. The document cites a wide array of “inflammatory and toxic responses after exposure to microorganisms isolated from damp buildings, including their spores, metabolites, and components,” as well as evidence that mold exposure can increase risks of rare conditions like hypersensitivity pneumonitis, allergic alveolitis, and chronic sinusitis.

Twelve years ago in New Orleans, Katrina similarly rendered most homes unlivable, and it created a breeding ground for mosquitoes and the diseases they carry, and caused a shortage of potable water and food. But long after these threats to human health were addressed, the mold exposure, in low-income neighborhoods in particular, continued.

The same is true in parts of Brooklyn, where mold overgrowth has reportedly worsened in the years since Hurricane Sandy. In the Red Hook neighborhood, a community report last October found that a still-growing number of residents were living in moldy apartments.

The highly publicized “toxic mold”—meaning the varieties that send mycotoxins into the air, the inhaling of which can acutely sicken anyone—causes most concern right after a flood. In the wake of Hurricane Matthew in South Carolina last year, sludge stood feet deep in homes for days. As it receded, toxic black mold grew. In one small community, Nichols, it was more the mold than the water itself that left the town’s 261 homes uninhabitable for months.

Researchers from the Natural Resources Defense Council held a press conference after Katrina about dangerously high levels of mold spores in the air. The group accused the Environmental Protection Agency of focusing only on exposures like arsenic, lead, asbestos, and pollutants such as those found in gasoline, while ignoring mold exposure.

The overwhelmed EPA did at the time issue radio announcements and distribute brochures encouraging people to wear respirators when reentering flooded buildings, particularly when cleaning and ripping out drywall. These are occupational exposures that fall mainly on manual laborers.

The more insidious and ubiquitous molds, though, produce no acutely dangerous mycotoxins but can still trigger inflammatory reactions, allergies, and asthma. The degree of impact from these exposure in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina is still being studied.

Molds also emit volatile chemicals that some experts believe could affect the human nervous system. Among them is Joan Bennett, a distinguished professor of plant biology and pathology at Rutgers University, who has devoted her career to the study of fungal toxins. She was living in New Orleans during the storm, and she recalls that while some health experts were worried about heavy-metal poisoning or cholera, she was worried about fungus.

“I’m still surprised it didn’t receive more attention from the scientific community, she said in a recent interview. “The city was rife with mold; everything organic decayed. A few people did some very superficial spore counts and they were off the scale, but at the time almost no one studied it because the focus was elsewhere. So I did my own study.”

The smell of the fungi in her house got so strong after the flooding that it gave her headaches and made her nauseated. As she evacuated, wearing a mask and gloves, she took samples of the mold along with her valued possessions. Her lab at Rutgers went on to report that the volatile organic compounds emitted by the mold, known as mushroom alcohol, had some bizarre effects on fruit flies. For one, they affected genes involved in handling and transporting dopamine in a way that mimicked the pathology of Parkinson’s disease in humans.

“More biologists ought to be looking at gas-phase compounds, because I’m quite certain we’ll find a lot of unexpected effects that we’ve been ignoring,” said Bennett.

This is where Trump’s words in support of Houston ring hollow.

Under his administration, the funding of science to better understand the health consequences of mold exposure stands to be slashed. Meanwhile, the significance of mold in human lives is expected to increase with rising sea levels and catastrophic weather events. The perennial intensification of severe weather patterns over the Gulf Coast has made flooding increasingly common, at least partly due to the warming of the ocean.

The Environmental Protection Agency, which would typically be tasked with mitigating the health effects of mold in Houston, is currently uprooting the regulations intended to reduce carbon emissions that raise the likelihood of severe weather events. The agency stands only less equipped now to deal with environmental mold contamination than it did in New Orleans.

In Houston, short-term rescue funding is essential to saving lives, and supporting it is politically necessary. But most of the looming threats to human wellbeing will outlast the immediate displays of concern. They will play out when the water and the cameras are gone, and when emergency funds allocated to Houston are exhausted. Mold will mark the divide between people who can afford to escape it and people for whom the storm doesn’t end.

James Hamblin, MD is a senior editor at The Atlantic, where this article was originally published.

NEXT STORY: Charlottesville Mayor Apologizes to Council, Will Surrender ‘Some of His Assumed Autonomy’