Trump's Opioid Commission Calls for a State of Emergency

And for giving every police officer naloxone, the drug that reverses overdoses

A government opioid commission chaired by New Jersey Governor Chris Christie has called for President Trump to declare a state of emergency in dealing with the opioid epidemic, which now kills more than 100 Americans daily.

Such a declaration, which several states have already made, “would empower your cabinet to take bold steps and would force Congress to focus on funding and empowering the executive branch even further to deal with this loss of life,” the commission wrote in a report released Monday. The commission also includes Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker, North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper, former Congressman Patrick Kennedy, and the Harvard Medical School psychobiology professor Bertha Madras.

The report recommended a number of other reforms to opioid treatment and overdose prevention, many of which will make it easier for addicts to get treatment.

They recommend changes to law enforcement, such as arming all police officers with naloxone, a medication that reverses opioid overdoses, and improving the detection of fentanyl at the border.

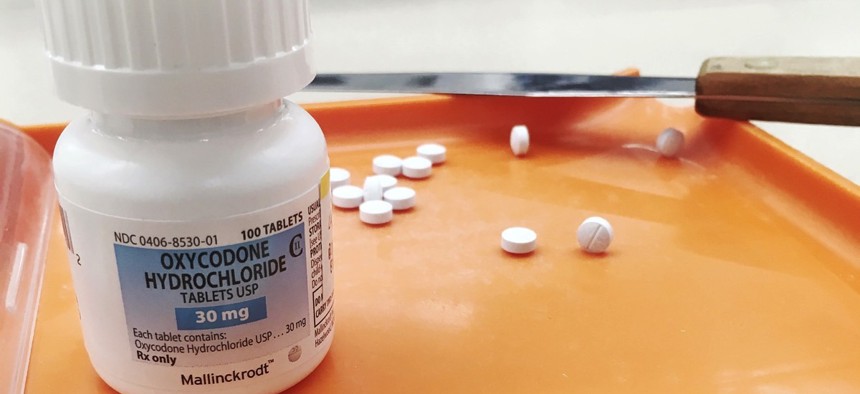

Because most heroin addicts start with prescription painkillers, they recommend improving training on painkiller prescribing for doctors and forcing state prescription-tracking programs to share their information by July 2018. (Forty-nine states have these so-called “prescription-drug monitoring programs,” but not all coordinate with each other, the report notes.)

Finally, the report urges the closing of several loopholes around medication-assisted recovery treatment for addicts. The report recommends that states be granted waivers to allow federal Medicaid funds to reimburse treatment in facilities with more than 16 beds, and that all treatment facilities offer medication-assisted treatment, such as buprenorphine. Some providers believe these drugs don’t constitute true recovery or sobriety.

Regulators, they write, should fine health plans that violate mental-health parity laws, meaning they illegally restrict mental-health or addiction benefits to a greater degree than physical health benefits. Finally, the commission suggests relaxing medical privacy laws so that the families of addicted patients can get updates on their relative’s medical status.

This interim report is expected to be followed with a final report in October. Before then, the commission says it will conduct “a full review of federal funding and programs and obstacles and opportunities for treatment.” Among other issues, it hopes to examine anti-drug programs aimed at kids and “satisfaction ratings” for doctors, which are considered to be a potential factor in the overprescribing of painkillers.

The commission is separate from the Office of National Drug Control Policy, though the ONDCP submits recommendations to the commission. It’s not clear how much of the commission’s report the White House will take up, if any. Trump established the commission through an executive order in March, but in May he proposed cutting 95 percent of the ONDCP’s budget. Reducing funding for Medicaid, as several of the Republican Obamacare-repeal health bills aimed to do, would also severely affect opioid addiction treatment. Medicaid pays for about a quarter of all opioid-addiction treatment prescriptions.

Olga Khazan is a staff writer for The Atlantic, where this article was originally published.

NEXT STORY: Trump's Opioid Commission Calls for a State of Emergency