The Case Against Library Fines—According to the Head of The New York Public Library

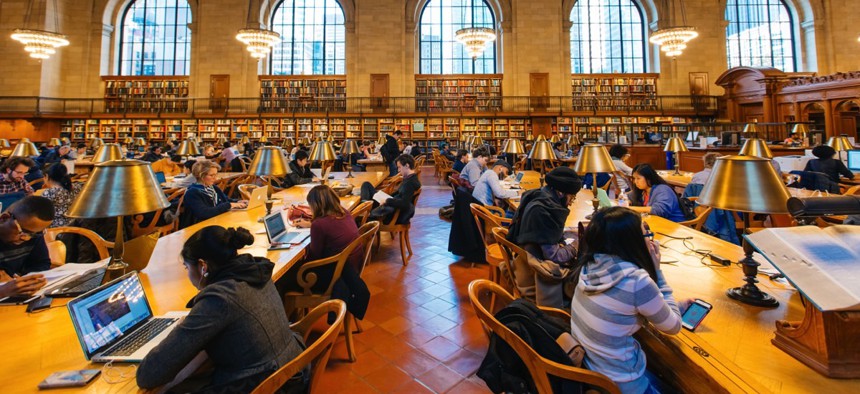

The New York Public Library.

Connecting state and local government leaders

For many families across the US, library fines are a true barrier to access.

There’s no doubt that we are currently living in a fractured world, one in which the divide between rich and poor is widening, opportunities for the disenfranchised are declining, and the lines between fact and fiction are increasingly blurred.

Public libraries are on the front lines every day, combatting these threats to our democracy. Whether loaning wi-fi hotspots to give patrons access to the internet and help close the digital divide, helping immigrants learn English, offering free citizenship classes, providing early literacy programs to close the reading gap, or simply loaning books (and, yes, people still read books—circulation at The New York Public Library went up 7% last year over the previous year), libraries ensure that no one—regardless of beliefs or background—faces barriers to learning, growing, and strengthening our communities.

It is because of this role, so crucial to our democracy of informed citizens, that I and many others at libraries across the country have been seriously evaluating the complex and long-standing issue of library fines – and whether to do away with them.

While relatively small library fines have been a punchline in pop culture over the years (Jerry Seinfeld’s “library cop” is an icon, for example), the fact is that for many families across the US, library fines are a true barrier to access. At The New York Public Library, $15 in accrued fines prohibits one from checking out materials. The reason for this policy may be obvious—it’s incentive to get books returned and back on our shelves—but is it really effective? For those who can afford the fines, paying a small late fee is no problem, so the fines are not a particularly strong incentive. On the other hand, for those who can’t afford the fines, they have a disproportionately negative impact.

At our 125th Street Library in Harlem, for instance, a young mother tried to check out a wi-fi hotspot so her daughter could do her homework. Homeless, the family couldn’t afford broadband internet, and her daughter’s grades suffered. Unfortunately, her library card was blocked, not because the family was irresponsible, but because one night, they were abruptly moved from one shelter to another, and in their haste to leave, they left behind a library book and DVD. The fines accumulated quickly, and without any way to pay them, their only hope for internet access was no longer available.

Our branch managers have the authority to use their good judgment to waive fines, and in this case, that’s exactly what happened. But that piecemeal, personal approach isn’t a solution.

In October, The New York Public Library, along with the Brooklyn Public Library and Queens Library, took a step in the right direction, offering a one-time fine amnesty for kids and teens. All students got a fresh start, no questions asked, hopefully prompting them to return and use our array of free resources.

One month in, we saw successes. About 41,000 kids and teens, or 10% of those who previously had fines, used their library cards to access library resources. Of those 41,000, 11,000 had blocked cards or a lapsed relationship with the library, meaning they hadn’t used the library for at least a year. So we know 11,000 kids and teens have rekindled their relationship with reading, learning, and libraries one month after we offered the amnesty. We will continue to monitor this, as we expect numbers to continue to increase as we continue to get the word out about the program.

While I am proud of this initiative, it is a one-time solution to a problem that is not going away. Before the fine forgiveness program, at The New York Public Library, 20% of our 400,000 juvenile and young adult patrons had blocked library cards; nearly half of those were concentrated in the poorest quartile of our branches. In addition, we know the heartbreaking truth: that there are families who refuse to even use the library for fear of accumulating fines.

These realities have prompted several library systems to experiment with fine elimination over the last few years. The relatively small Stark County District Library system in Ohio, as one example, waived fines in 2014, and one year in, saw positive results – an 11% increase in circulation, an increase in items checked out, and no significant increase in lost items, those never returned. The Columbus Metropolitan Library announced a fine-free 2017. Just this month, the Yankton Community Library in South Dakota—inspired by our efforts in New York—decided to experiment with fine-free borrowing. And the Omaha Public Library recently announced that is exploring the possibility of fine free borrowing in its system.

In 2011, The New York Public Library launched a program called MyLibraryNYC to provide fine-free borrowing to students at eligible NYC public schools. Kids in the program borrow 37% more materials than kids who are not in the program; teens 35% more. At the same time, the number of lost items represents a small percentage of all items checked out as part of the program, showing that kids are indeed bringing the books back. Positive test cases like this show that fine-free lending is an experiment worth broadening. I would like to lead the way, but for large urban systems, the lost revenue would be significant, and a serious issue that must be addressed before we can move forward. While library systems have many sources of funding, the fact is fines do contribute (sometimes millions of dollars) and that needs to be addressed.

Over the next year, I plan to meet with my counterparts at library systems across the US to discuss this issue, and develop innovative ideas that would allow systems big and small to eliminate this barrier to access. I hope that we can count on our partners in government and on the private side—those who support early literacy, the end of the digital divide, and opportunity for all—to work with us, perhaps to help libraries recoup lost revenue and examine eliminating library fines. Support from the JPB Foundation, which works to improve quality of life for low-income people, is what allowed us to do New York City’s one-time amnesty. Innovative, consistent support could ensure that financial hardships do not prohibit a family from taking advantage of a public resource built to help them.

I understand there are some who will balk at this experiment, wondering if the elimination of fines poses a “moral hazard”? To be clear, I’m not advocating a system with zero accountability. Patrons would need to return their items before checking out new ones, and still pay for lost items. I’m advocating a system in which a family does not need to choose between dinner and using the public library.

And so I must ask—what is truly the greater moral hazard? Having fines or not having fines? In my view, teaching kids that the library is not an option for the poorest among them is absolutely unacceptable.

Anthony W. Marx is the president and CEO of The New York Public Library system. This article was originally published by Quartz.

NEXT STORY: Congress Won’t Act; Now Community Health Centers Weigh Closures