The Long History of Black Officers Reforming Policing From Within

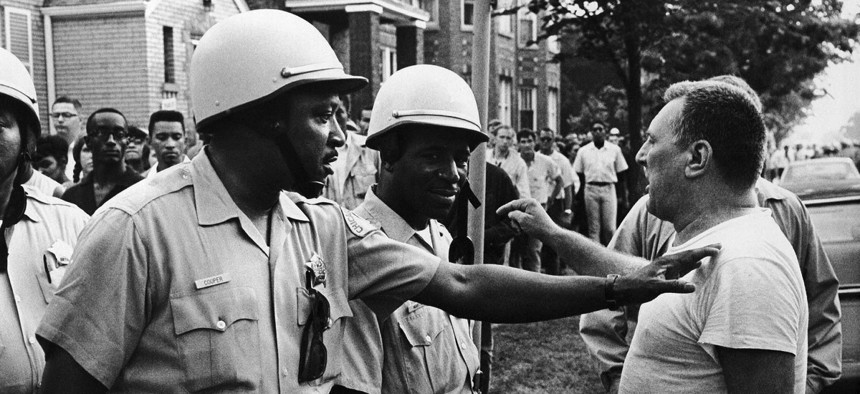

Chicago Policeman Eddie Cooper (left), places his hand on the shoulder in a restraining action of an unidentified man who protested a civil rights march in the Chicago area, Aug. 22, 1966. (AP Photo)

Black Lives Matter and Donald Trump’s agenda are inspiring some police to more vocal advocacy. But their project—ending racial bias in the profession—is a decades-old one.

When it comes to law enforcement in America, there are two culture wars under way.

One has been championed at the federal level by the Trump administration: an effort to rigorously defend police and shift public policy away from punishing officer misconduct. But the second, less visible—and, in some ways, opposite—war has been ongoing at the local level for over a half-century, with African American officers working to mitigate racial bias and abuse of power from within the profession.

President Trump and other tough-on-crime advocates argue they are “backing the blue.” This obscures the fact that many law-enforcement leaders openly share activists’ concerns. Although not all black officers back criminal-justice reform, and many who do are not black, African Americans have a long history of advocating for change in their own departments. Despite the current cultural and governmental challenges facing policing reform, some of the biggest obstacles are not particular to the Trump era, leaders told me. Rather, they are much older conflicts that aren’t easily influenced by federal politics.

After decades of being ineligible for top positions, some black law-enforcement leaders today try to shape how officers think about racism and inequality. The history of black Americans’ integration into law enforcement shows how this internal resistance has developed over time. Historian W. Marvin Dulaney details this progression in cities across the country in his book Black Police in America.During slavery and Reconstruction, a few cities and states in the South hired black officers to fill undesirable positions or increase departments’ size, but their brief tenures often ended in backlash from white citizens. (During slavery, the officers were freedmen.) In the North and Midwest, newly elected mayors appointed some of the first African American police as a reward for black votes in the late 1800s and early 1900s. States in the Deep South that had previously outlawed black police officers during Reconstruction didn’t hire them again until the 1930s or 1940s, after protests from African American communities.

Across the country, more black officers joined during the Jim Crow era, and they were commonly assigned to patrol only black neighborhoods. “They were often denied promotions and transfers to other divisions. In some cases they were not allowed to wear their uniform to or from work for fear of some altercation that could occur with a white citizen,” said Alan Thompson, a University of Southern Mississippi criminal-justice professor.

Their treatment of minorities was shaped by social norms and growing up in segregated communities; through the early 1900s, black officers were often aggressive toward minorities. But by the 1930s and 1940s, there were new cohorts of black police who actively adopted a more respectful posture toward people of color and began building ties to black community organizations like the NAACP. Some of them were energized by the community outcry that led to their hiring, others by their growing numbers.

Despite pushback from white leadership, local black police unions began popping up in cities across the country, and their members sometimes criticized policies that harmed minorities. Thompson said that in the social upheaval of the 1960s—as departments had to “back away from explicit practices” segregating police—some started relying on black officers to deescalate tensions between police and black communities, and to improve their own reputations. As the first black mayors of major cities were elected in the late 1960s and early 1970s, some of them appointed their cities’ first black police chiefs.

Still, their ascendancy didn’t always translate to more progressive departments: Black chiefs who avoided battles over minority representation in their hiring practices, for example, were celebrated by white colleagues for having an evenhanded approach. Some of the first black officers integrated into majority-white precincts found that openly calling out racial bias could threaten their careers. Donald Jackson, a sergeant within the Los Angeles Police Department, told The New York Times in 1988 that a “fellow officer, who was white, [told] me that if he calls blacks ‘niggers,’ it shouldn’t offend me because I’m blue, not black.” Jackson said that when he spoke out against such slurs, he was ostracized within his department.

Former New York homicide detective, Bernard Edwards, started his career in 1956 as one of four black officers patrolling Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood. He told me the work was “sometimes … very frustrating”:

Black people never fully understood black cops were looking out for them because we didn’t advertise it. You had to be impartial. I wouldn’t say, “I don’t like the way you treated that black guy.” I would say “I don’t like the way you treated Harry Brown.” But cops are smart and they’ll put two and two together. … Everybody who comes into the department wants to advance. Before you go anywhere, someone’s going to ask your sergeant, “What kind of guy is that?”

Now, black police leaders can be more forthcoming on race in policing, though African Americans are still a distinct minority in the field, representing just 9 percent of officers in 1987 and 12 percent in 2013. Some I spoke with told me they’ve felt more motivated to advocate for reform since the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement and since Trump’s inauguration.

“I think we can’t make changes if we’re not part of the system,” said Jefferson County Sheriff Zena Stephens, the first African American female sheriff elected in Texas. “If I have a skillset that can prevent this misunderstanding or this trainwreck that seems to be happening in society, then I think I have a responsibility to do so.”

Officers are still targeted for being black. Last year, as Stephens was standing outside her campaign headquarters, a man drove by and shot into its glass front door. Almost 20 years before, Orange County Sheriff Jerry Demings, the president of the Florida Sheriffs Association, was sent threatening letters when he became the first African American chief in Orlando in 1998. His “white colleagues have different priorities as leaders,” he told me, “but some of us can’t shift away” from the way some minorities feel about police.

At the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation’s annual conference in September, a panel of black sheriffs and police chiefs was asked who they identify with more after incidents where a police officer has shot a black person. Patrisse Andrews, the chief in Morrisville, North Carolina, described her thought process:

“Every time I see any shooting, I’m a mother first. … Second, I identify as being a black woman, daughter of a civil-rights pioneer. I physically weep before I go to work. And then as I drive to work, I say, “Pull yourself together, because you’re chief. You can’t be walking in there teary-eyed.” And then I may break down when I get there and my officers see me weep. And I’m okay with that because they see that I’m human. … The way I get through it is, I own it. I’m a mom and a proud black woman, and I’ll never trade any of those things for law enforcement. Never, ever.”

In some cases, colleagues’ racial biases motivated officials to pursue leadership positions. Mitchell Davis, the police chief in Hazel Crest County outside of Chicago, gave me an example from early in his career. During his initial training, when a higher-ranking officer shadowed him on a night shift, Davis stopped a white drunk driver and was instructed to call the offender’s relative to pick him up. He later stopped a black drunk driver and was instructed to tow his car and arrest him. “Now, I was in training, so I couldn’t not do it. But it was a gesture saying, ‘I’m going to show you how we treat these people,’” Davis said. “I’ve seen instance after instance where these things happen.”

As part of reforming their organizations’ culture, some officials have tried to de-stigmatize the Black Lives Matter movement. At the CBC panel, Andrews said she’s sympathetic to the activist group, in part, because her daughter identifies with it. “When I posted [a photo] on Facebook about being proud of my daughter, I didn’t even realize she was wearing a Black Lives Matter shirt and I was wearing a police shirt,” Andrews said. She tells her colleagues to avoid belittling the movement as a passing phase and encourages them to “take a seat at the table.”

Multiple officials I spoke with share some of the same grievances as Black Lives Matter. For example, they unanimously disapprove of police unions protecting officers who are fired for misconduct. Indeed, “we’ve all been sued [by police unions],” Davis said, referring to cases where he’s been challenged for firing employees he alleged behaved unfairly toward minorities.

The Fraternal Order of Police, the largest police union in the United States, promotes a defend-at-all-costs culture, some suggested. “When something controversial goes on with the police in Chicago, the media interviews the union president—who’s not even part of the administration of the police department,” Davis lamented. In recent years, the FOP has offended some of its black members by investing in the defense fund for Darren Wilson, the Ferguson, Missouri, officer who shot Michael Brown in 2014; hiring Jason Van Dyke, the Chicago officer who was fired for shooting Laquan Mcdonald 16 times in 2014; and endorsing Trump’s candidacy.

Police unions’ opposition to reform well predates Trump; as a New Yorker writer noted last year, “most of them were formed as a reaction against public demands in the 1960s and 1970s for more civilian oversight of the police.” In that sense, the administration doesn’t change what has never given way. During the Obama administration, the FOP butted heads with members of the Presidential Task Force on 21st Century Policing and publicly opposed measures like Barack Obama’s executive order curtailing police access to military weapons. In August, the FOP cheered as Attorney General Sessions announced Trump would nullify the directive.

And policing at the local level is not as tied to the federal government’s agenda as a layperson might think. The officials suggested the law-and-order Trump era has put a strain on their personal relationships with white colleagues, but insist it doesn’t affect their leadership strategies. For example, the president making it easier for police to acquire military-grade weapons doesn’t mean each chief or sheriff will choose to do so.

Police leaders have varying degrees of autonomy, but none are directly beholden to the White House or the Justice Department. It’s local officials that matter most. “The Orlando Police Department was a community-policing agency before I became chief, and my goal was to take it to the next level,” Demings said. “Having the mayor and city council support me in my endeavors was monumental because all of these things have a price tag.” Trump’s “policies haven’t caused any problems for me yet,” Stephens said. “The people who work for me know my mindset and my expectations.”

While African Americans in law enforcement have gained a considerable amount of traction in the short time they’ve had access to the profession’s higher ranks, they still bump up against their colleagues’ discriminatory practices and points of view. That’s just the essence of the “chess game” black officers play as they try to influence how policing is done, as Demings put it at the CBC panel. And that’ll continue into the next administration, too. “Day to day, [black law-enforcement leaders] are putting out fires. But those with a long-term vision are trying to do what others did for them, which is bring along the next generation,” Thompson said. “They’re slowly chipping away at the stone.”

Taylor Hosking is an editorial fellow at The Atlantic, where this article was originally published as part of the part of “The Presence of Justice” project, which is supported by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge.

NEXT STORY: Santa Ana Winds Fuel Quickly Moving Fire in Southern California