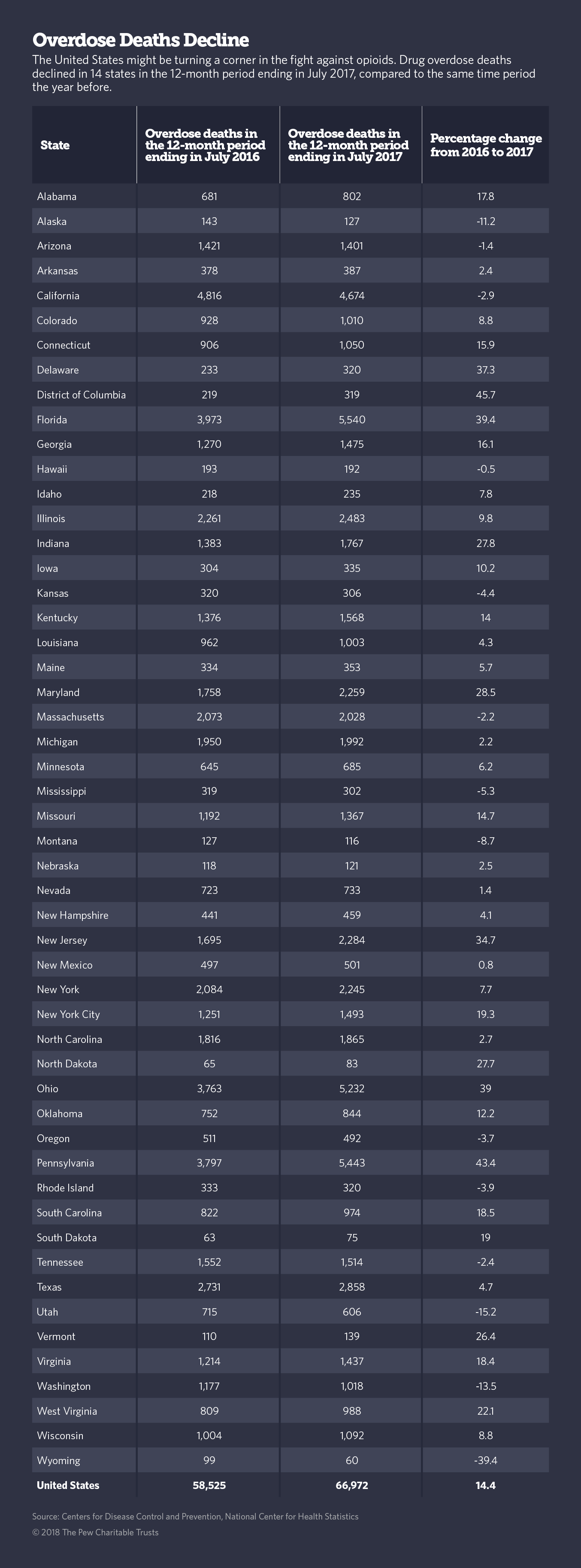

Good News: Overdose Deaths Fall in 14 States

Shutterstock

But the bad news: “But we’re still seeing rates of overdose that are leaps and bounds higher than what we were seeing a decade ago and far beyond any other country in the world.”

This article was originally published by Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts and was written by Christine Vestal.

New provisional data released this month by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows that drug overdose deaths declined in 14 states during the 12-month period that ended July 2017, a potentially hopeful sign that policies aimed at curbing the death toll may be working.

In an opioid epidemic that began in the late 1990s, drug deaths have been climbing steadily every year, in nearly every state. A break in that trend, even if limited to just 14 states, has prompted cautious optimism among some public health experts.

“It could be welcome news,” said Caleb Alexander, an epidemiologist and co-director of Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Drug Safety and Effectiveness.

“If we’re truly at a plateau or inflection point, it would be the best news all year,” he said. “But we’re still seeing rates of overdose that are leaps and bounds higher than what we were seeing a decade ago and far beyond any other country in the world.”

The reported drop in overdose deaths occurred in Wyoming, Utah, Washington, Alaska, Montana, Mississippi, Kansas, Rhode Island, Oregon, California, Tennessee, Massachusetts, Arizona and Hawaii. That compares with declines in only three states—Nebraska, Washington and Wyoming—reported for an earlier 12-month period that ended in January 2017.

But even as more states saw a drop in deaths, several saw death spikes of more than 30 percent, most likely due to the increasing presence of the deadly synthetic drug fentanyl in the illicit drug supply, drug experts say. Those are Delaware, Florida, New Jersey, Ohio and Pennsylvania, along with the District of Columbia.

Published monthly since August, the new CDC statistics are a compilation of death certificate data from all 50 states for a rolling 12-month period ending seven months prior to release of each report. The seven-month delay is roughly the amount of time it takes for states to complete death investigations and report causes of death, and for the CDC to compile the data.

Previously, the CDC only made death data available once a year and it was 12 to 14 months behind. In a fast-moving opioid scourge, epidemiologists say the increased frequency of overdose death reporting is a welcome improvement.

Farida Ahmad, a public health expert with the CDC, cautioned that the monthly provisional death numbers are subject to change because as many as 2 percent of death certificates for the time period have not been reported. A final death count for 2017 will not be available until November, she said.

Increased Volatility

In Alaska, where deaths declined more than 11 percent between the 12-month period ending July 2016 and the 12-month period ending July 2017, the state’s public health chief, Jay Butler, said the trend has been cause for some optimism.

The greatest portion of that decline was in prescription opioids, drugs such as OxyContin, Percocet and Vicodin, Butler said.

“And we may be seeing a plateauing, if not a decline, in overdose deaths from heroin,” he added. “The bad news is that we’re seeing more deaths from fentanyl.”

Indeed, fentanyl-related deaths spiked more than 70 percent nationwide in the 12-month period ending July 2017, according to the report.

“Using illicit drugs has always been a game of roulette,” Butler said. “There’s just more bullets in the chamber now.

“When the epidemic was driven primarily by prescription opioids, we saw a smoldering and chronically escalating problem,” he said. “Now we’re seeing outbreaks and clusters of death resulting from bad batches of heroin or counterfeit pills laced with fentanyl.”

Still Rising

The recent drop in opioid deaths in some states might be significant, experts say, but they caution it should be seen in the context of the worst drug death epidemic in U.S. history.

In 2016, the annual overdose death count reached nearly 64,000, more than three times as many as in 1999. It surpassed the number of fatalities from automobile crashes and homicides, becoming the No. 1 cause of death among Americans 50 and younger.

Aside from the 14 states seeing declines, there are few signs of relief ahead.

Nationwide, the death toll is still rising, although possibly at a lower rate than in the past two years. According to the CDC’s current provisional report, the total number of overdose deaths increased 14 percent in the 12-month period ending in July 2017, compared to a 21 percent increase in the 12- month period that ended in January 2017.

One reason could be a decline in the availability of prescription painkillers. Even as overdose deaths spiraled over the last five years, the rate of prescribed opioid consumption began to decline.

That could mean lower rates of heroin use, addiction and overdose deaths in the future, Alexander said. A vast majority —86 percent—of young, urban injection drug users started misusing prescription opioids before turning to heroin, according to surveys by the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Another likely reason for a tapering in death counts is the widespread use of the overdose antidote naloxone, public health experts say.

“It’s hard to imagine how high the death toll would be without naloxone,” said Michael Kilkenny, the Cabell-Huntington public health director in West Virginia.

“It’s a little too soon to tell,” he said, “but we may be seeing the beginning of a decline in the number of deaths in Huntington,” a small city that has the highest overdose death rate in West Virginia, the state with the highest overdose death rate in the country.