Lawmakers dig deeper into Hawaii's false missile alert

Connecting state and local government leaders

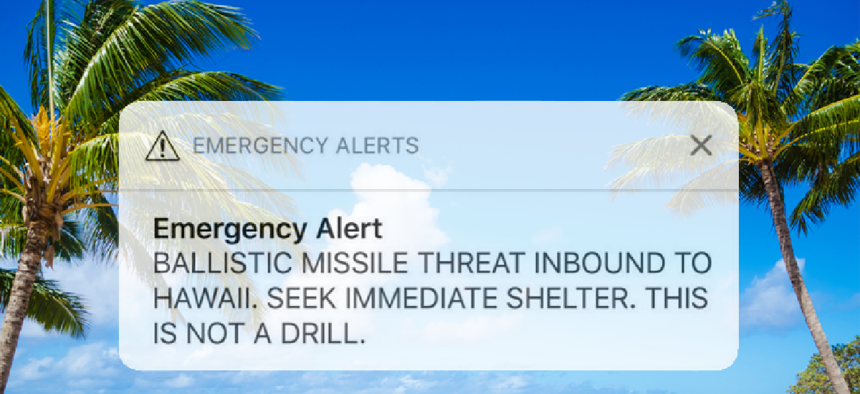

During a April 5 field hearing federal officials questioned whether the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency was ready to roll out a system to alert residents of an incoming missile attack.

At a April 5 field hearing in Honolulu, federal officials questioned whether the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency was ready to roll out a system to alert residents of an incoming missile attack after an errant warning sent on Jan. 13.

Adm. Harry Harris Jr., a Navy Commander within the U.S. Pacific Command, laid out the timeline for how the events unfolded. At 8:07 a.m. the alert was sent by HI-EMA, which led to a half an hour's worth of clarifications by state officials on social media to let people know there was no threat. A false alarm notification was finally sent at 8:45 a.m. Lawmakers focused on this 30 minute window in their statements and questions.

“There were serious failures at the point of alert origination -- the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency. These errors were human and operational,” Federal Communications Commission Commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel testified during the hearing, which was held by the Senate Commerce Committee's Subcommittee on Communications, Technology, Innovation and the Internet.

The state agency said it is taking steps to improve its processes.

After apologizing for the false alarm -- “especially the 30-minute delay in correcting the message error” -- HI-EMA Director Maj. Gen. Arthur Logan assured lawmakers that “we have taken immediate steps to guard against a false alert and to ensure that such an event will not happen again.”

These steps include working with the vendor that provides the connection to the warning system to ensure the software has “color differences between test and real world alert icons to click on.” Hi-EMA is also working on implementing two-factor authentication that would be required to send certain warnings, such as a missile alert, he said in testimony.

The ability to be notified of an incoming missile is especially important for Hawaii because of North Korea's escalating threats to America and its expanding nuclear capabilities, Logan said.

“The experts tell us that the flight time of an ICBM from North Korea to the State of Hawaii is approximately 20 minutes,” he said in his testimony.

"Because time is of the essence with ballistic missile preparedness," Logan said, the state began a preparedness campaign plan, "well before we completed a tangible Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, and High Explosive (CBRNE) response Annex to Hawaii’s 2014 Catastrophic Plan."

But lawmakers questioned whether the state was really ready to launch the mass notification system.

“Was that premature?” asked Rep. Colleen Hanabusa (D-Hawaii).

HI-EMA did begin using of the system before all the plans and procedures were in place, Logan admitted, but he said that was necessary because of the threats and missile tests coming from North Korea.

“I felt it was imperative that we do something rather than just wait for a launch and then try and react,” Logan said.

This campaign has been suspended as a result of January’s false alarm.

Sending a missile alert is not a responsibility state-level agencies should be tasked with, Sen. Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii) said in the hearing.

“If we are at war, there is no reason not to inform every American citizen,” Schatz said. “The idea that there should be a regional alert about an incoming ICBM is preposterous.”

Schatz has introduced the Authenticating Local Emergencies and Real Threats (ALERT) Act, which would give the federal government the primary responsibility of notifying the public of a missile threat. The Reliable Emergency Alert Distribution Improvement (READI) Act, introduced April 5, would update the broadband and mobile phone systems that deliver these messages ensure they don’t fall behind as technology progresses, he explained in the hearing.

Schatz also pushed Antwane Johnson, the director of continuity communications for the Federal Emergency Management Agency, on the lack of best practices for state and local agencies to follow when it comes to missile alerts.

“How is any state going to follow an example is there are no examples to be followed?” Schatz asked.

Johnson acknowledged that several states reached out to FEMA looking for guidance in this area after HI-EMA’s mistake and said a number of best practices have evolved over the last few years for emergency alerts in general. He did not expand on what these best practices are.

NEXT STORY: LinkNWK lands on New Jersey sidewalks