Multiple Cities Face Legal Challenges Over Anti-Panhandling Laws

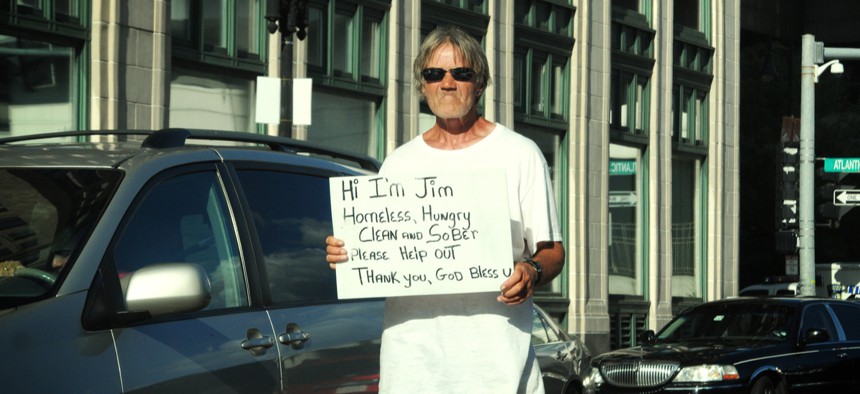

Shutterstock

“... [W]henever a new city does consider passing a new panhandling law where they didn’t have one before, they’re immediately either sued or they get a lot of pushback,” according to Cleveland State University law professor Joseph Mead.

Cities across the country may continue to reconsider ordinances regulating panhandling as multiple court cases successfully argue that the rules are unconstitutional.

“My sense is, having followed this pretty closely for the last year or two, that whenever a new city does consider passing a new panhandling law where they didn’t have one before, they’re immediately either sued or they get a lot of pushback from advocates,” Joseph Mead, a law professor at Cleveland State University who litigated several anti-panhandling cases on behalf of the American Civil Liberties Union, told Route Fifty in an interview. “I think that as the constitutional issues become more and more clear, cities are going to have no choice but to do something about the laws on the books.”

The argument that panhandling is constitutionally protected under the First Amendment stems largely from a 2015 U.S. Supreme Court case involving an Arizona church that rented space at an elementary school and placed signs around the area with details about its services.

City ordinances limited the size of temporary signs based on the messages they conveyed. Campaign signs, for example, could be as large as 32 square feet, could stay in place for months and were generally unlimited in number. But signs announcing church services and similar events could only be as large as 6 square feet, could be displayed only just before and after an event, and were limited to four per property, according to The New York Times.

The Supreme Court ruled 9-0 that a rule placing tougher regulations on certain types of signs than others could not be upheld under the constitution. In subsequent cases, lawyers with the ACLU have successfully expanded that argument to include panhandling as a protected class of speech, forcing cities from Sacramento to Oklahoma City to Slidell, Louisiana to reconsider existing ordinances banning or regulating the practice.

Other cities have changed ordinances without direct legal intervention. Officials in Columbus, Ohio, instructed police officers to stop enforcing existing panhandling ordinances last June over fears the city might potentially face legal challenges after lawsuits led Dayton, Cleveland, Akron and Toledo to repeal or revise their own panhandling ordinances, according to the Columbus Dispatch.

“Every time a city amends its law, there’s press coverage and that causes other cities to examine what they’re doing,” Mead said.

As a result of that process, some cities have gotten creative in their methods to attempt to curb panhandling. In Fayetteville, North Carolina, officials passed an ordinance granting police the authority to issue civil citations to people who give money to panhandlers through car window. A first offense garners a written warning, with a $25 fine for the second violation and $100 for the third, the Fayetteville Observer reported.

The city of Albuquerque instituted a similar law last year and was quickly challenged in court by the ACLU, Mead said. The fate of the ordinance remains unclear, but the city is not enforcing it while the lawsuit proceeds.

In Charleston, South Carolina, city officials last month passed an ordinance to ban sitting or lying on certain city sidewalks between 8 a.m. and 2 p.m. City Council members said the ban was necessary because the streets in question “were built in the eighteenth century and are narrow by current standards,” and the congestion “creates a safety hazard,” The State reported.

But the move is widely seen as an attempt to stop panhandling in popular tourist areas. Charleston tried to prohibit panhandling outright in 2014 but overturned the ban amid pressure from the ACLU. Because of that, the new ordinance has exceptions—sitting or lying is allowed in certain parts of town and in cases of medical emergency, disability and for children in strollers. It’s also permissible for people watching parades or participating in festivals, according to The State.

Though that ordinance is complex and thus far untested, there’s some precedent for similar laws being overturned in court.

In 2015, a federal judge ruled that cities must prove that laws are needed if they make panhandling more difficult to do--even if the laws don’t mention it specifically.

“Cities can say, ‘Well, we had to pass this law for safety reasons,’ but then it becomes a proof issue,” Mead said. “They have to prove that was the real reason behind the law, and that there’s no other way they could accomplish the same goal. It’s still vulnerable to challenge, it’s just a different type of argument that has to be made. If it doesn’t talk about panhandling directly, it can be harder.”

Kate Elizabeth Queram is a Staff Correspondent for Government Executive’s Route Fifty and is based in Washington, D.C.

NEXT STORY: Iowa Can Breathe a Sigh of Relief This Spring. At Least for Now.