This Utah Library System Will Distribute Overdose-Reversing Naloxone to Residents

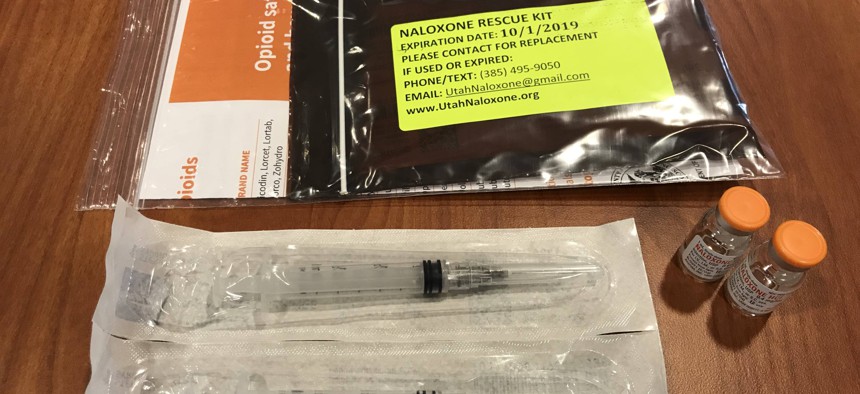

Each naloxone kit contains two syringes of the injectable overdose antidote, along with an information card. Salt Lake County Library

Connecting state and local government leaders

Distribution of the kits is an extension of a previous push to train library staff to spot the signs of an opioid overdose and administer naloxone directly to library patrons in distress.

Library patrons in Salt Lake County, Utah, can visit 18 branches to do research, check email or get a recommendation for the perfect beach read. As of this week, they can also stop by the county’s libraries to pick up a naloxone kit containing two injectable syringes of the opioid-overdose reversal drug—no questions asked.

Distribution of the kits, a partnership between the county libraries, the University of Utah and nonprofit Utah Naloxone, is an extension of a previous push to train library staff to spot the signs of an opioid overdose and administer naloxone nasal spray directly to library patrons in distress. Combined, the two initiatives aim to offer community members a safe, nonjudgmental space to seek help.

“The library is all about lifelong learning and providing a positive experience and a welcoming space,” Liz Sollis, a spokeswoman for the Salt Lake County Library system, told Route Fifty. “We are committed to the community and we want the community to know that we’re there for them, in any circumstance. I think it’s a great tool for us to have.”

Overdoses occur when opioids attach to receptors in the brain, sending signals that block pain, slow breathing and have a general calming, antidepressant effect. Because opioids affect parts of the brain that regulate breathing, high doses can cause respiratory distress and, in some cases, death. Naloxone reverses the overdose by blocking the opioids. It cannot be used to get high and won’t harm a person who is not experiencing an overdose.

To date, no one has overdosed at a Salt Lake County library, though the idea of training librarians to administer the overdose antidote is relatively common nationwide. (In the past year alone, librarians in Philadelphia, Denver, San Francisco and Maryland have used naloxone to reverse overdoses.) But even in the midst of a nationwide opioid crisis, it’s still rare for libraries to dispense overdose kits to the public, said Dr. Jennifer Plumb, co-founder of Utah Naloxone.

“The push to get librarians to respond to overdoses has been going on for awhile, but in terms of libraries being a dispersal point or a public-access point, I’m not aware of any others,” Plumb told Route Fifty. “I can envision that there might be a library here or there that would be an access point, but I have not heard of another major library system like this, with 18 branches all throughout this large county, doing it.”

The naloxone nasal spray was provided to the libraries by the Salt Lake County Health Department, and Utah Naloxone is supplying the injectable kits, which are available for free to members of the public (starting at a maximum of two kits per person per day). Each branch will have an initial supply of 20 kits, which will be replenished as needed. Patrons do not have to provide personal information or answer any questions to receive a kit.

Because of that, library staff won’t know why people are requesting kits. Some might be addicts who want the antidote around in case of an overdose. Others could be relatives or friends of people struggling with addiction. The opioid crisis doesn’t discriminate, Sollis said.

“If you look at the rates and the population impacted by unintentional overdose deaths, they’re people in your community, your neighbors. These are moms and dads,” she said. “And I think there are more people than people realize who know someone who is struggling with opioid addiction.”

Librarians and staff members are undergoing training this week to learn to administer the injectable naloxone. That step is crucial, Plumb said, so that they can educate members of the public on how to use the kits on their own.

“To teach someone to use something is different than teaching someone to teach someone else to do something, so the training this week is a review of the important bits we’ve covered before—here’s what an overdose looks like, here’s when you use naloxone,” she said. “Then we go through a training card, which is everything they need to be sure to pass onto the next person.”

In addition to encouraging access to naloxone in pharmacies, Utah Naloxone distributes kits via partnerships with a handful of first-responder organizations, including the Salt Lake City Fire Department. Supplying libraries with the kits provides another outlet for people in need of help who may be uncomfortable accessing the medication through more traditional means, Plumb said.

“The thought process was, ‘What is non-threatening? What’s a trusted entity? What’s present everywhere?’" she said. "And libraries are just kind of all of the above.”

The library partnership was relatively easy to set up, Plumb said, partly because Utah Naloxone is well-known within the community.

“Since leading up to this we already had partnerships with the fire department and the police, there had already been preemptive discussions with the county,” Plumb said. “So the city and county attorney—this wasn’t a new dialogue to them. It didn’t take a lot of red tape to actually make this happen, but I think that’s because it had been a bit preloaded with our other projects.”

It’s unclear what the demand for kits will look like, though Sollis said the libraries have already fielded questions and requests from residents in the wake of local media coverage.

“Our branches are interested, and so is the community. We’ve had people ask about it on social media,” she said. “There’s a perception that there are only certain people who become addicted to or misuse medications or drugs, and the reality is that it could be anybody.”

Kate Elizabeth Queram is a Staff Correspondent for Government Executive’s Route Fifty and is based in Washington, D.C.

NEXT STORY: Cities Form New Racial Equity Network With Private Sector