New Industry Promises to Bring ‘Made in America’ Label to Fish

Belfast, Maine Shutterstock

Onshore fish farming in Maine moving ahead with support of local and state officials.

BELFAST, Maine — Here on the Penobscot Bay, an entirely new industry is offering the hope that the United States might become significantly less dependent on foreign sources to meet its huge appetite for seafood.

In Belfast, and further up the bay in Bucksport, investors are planning onshore farms to produce millions of salmon in processes that promise much less risk of disease and pollution than the offshore pens now used to grow much of the fish consumers purchase.

Regulatory questions surrounding the fish farms have preoccupied local governments here in Maine, and are also under consideration by state government and federal authorities. Local opponents, especially in Belfast, have raised all sorts of questions about the onshore technology, which has yet to be tested at the scale envisioned by proponents.

But the momentum seems with the onshore aquaculture entrepreneurs.

American consumers are eating 500,000 tons of salmon a year. That puts the fish in second place on the list of most consumed seafood species, with shrimp still holding a considerable lead. In third place is canned tuna, according to SeafoodSource. Nearly 95 percent of the salmon is imported from offshore farms in three countries: Norway, Chile and Canada.

Whole Oceans LLC, a Portland-based firm, announced in February 2017 that it would build a land-based aquaculture plant in Bucksport on a piece of the huge, abandoned Verso paper mill that once was at the center of the region’s economy. The company is ready to invest $75 million in its first phase and hopes to break ground about six months from now. The money will finance a large building fed by fresh and sea waters in which the young salmon will swim in circles for about three years as they grow to maturity.

Bucksport has welcomed the prospect of the salmon farm. It will provide a few dozen well-paying jobs and will be a large and welcome addition to the tax base in this town of 5,000 residents.

Whole Oceans plans to start with a facility capable of producing 5,000 tons of salmon a year. The company aspires to add capacity for another 20,000 tons in additional plants that could go in Bucksport and elsewhere in Maine. That would bring its investment up to $250 million, as Route Fifty reported last year. The company, said one of its executives, has a long-term, 20-year goal to move production in Maine all the way up to 50,000 tons, and thus to capture 10 percent of U.S. demand.

Belfast Debate

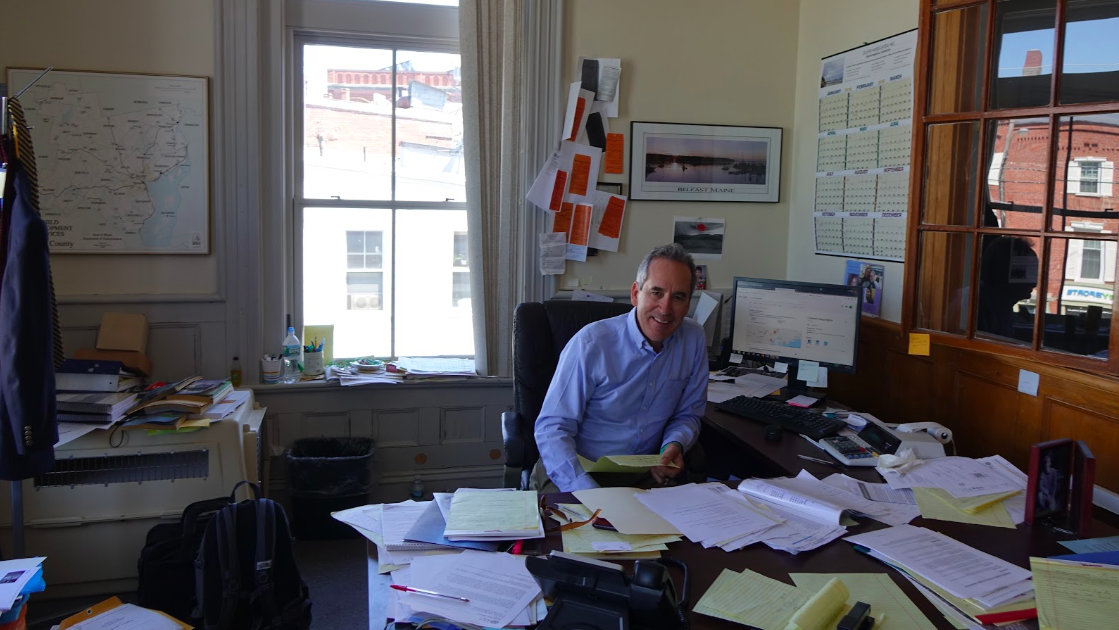

Downriver in Belfast, Nordic Aquafarms is encountering more opposition, even though the Belfast City Council in April unanimously approved a change in zoning to accommodate the plant—and City Manager Joseph J. Slocum is disinclined to accept opponents’ arguments. “We have heard them,” he said in a recent interview, “but we just disagree.”

Belfast has held three well-attended informational sessions at which company Eric Heim, chief executive officer of the Norwegian company, and others have described plans for the onshore salmon farm, and other experts have also weighed in. The last session, on June 12, “got a little heated,” Slocum observed.

Video of that session posted on the town’s website shows that more than half of the session was devoted to statements by experts from nonprofit institutions and by Heim. The Q&A portion of the meeting allowed critics to raise a variety of concerns about the project.

A recurring criticism has been that Belfast officials have not been open and transparent as they have moved to encourage Nordic Aquafarms to build its huge facility in their town. Officials conducted several months of talks with the company before publicly revealing that it wanted to locate in Belfast. The three evening public information sessions each lasted about two hours, but critics have complained that there’s not enough time to answer all the questions they have.

Slocum dismisses these questions about the procedures he and the city council have followed.

He said of the many private meetings his economic development team has held with companies interested in Belfast, “It’s like fishing. You can reel the fish to the side of the boat, but until you actually get him over the side, it’s not a catch.” The companies, he said, “want to get a feel for the town privately, without the glare of publicity, as they are conducting siting research.”

The town-sponsored public information sessions have informed citizens, and allowed them to comment—albeit not at much length or with much focus. Slocum emphasized that every concern about environmental, health and other effects of the fish farm will be addressed as Nordic Aquafarms applies for all the permits it needs from several state agencies. A disciplined public comment process, focused on individual aspects of the plant, will give the critics a chance to marshall their arguments as best they can, Slocum said, adding that “the biggest obligation of government is to have good processes.”

The company expects to file permit applications soon, it said in a “project update” in early June. The update added that “our aim is to commence construction in the spring of 2019.”

Slocum said the town has hired the Deloitte consultancy to study the Nordic Aquafarm’s record in Norway, where onshore fish farming is getting underway. But the city manager emphasized that he and the town council are strongly behind the project. The first phase, costing $150 million to build, would create 60 jobs. A second, larger phase, would create another 120 positions. Although direct employment is thus projected to be modest, the project will spawn a supply chain that will offer substantial opportunities to Maine entrepreneurs.

And Nordic Aquafarms would all of a sudden become the town’s biggest taxpayer. Slocum recited his careful analysis of the plant’s prospective contribution to the tax base. Even after accounting for various investment deductions and a reduction in state subventions for the local school district (because of the increase in local revenues), the plant’s first phase would add $877,000 a year to town receipts, Slocum calculates.

“You bet your life, I want that revenue,” Slocum said. “Everyone has a project that needs funding, and we can use the money.”

Unlike Bucksport, Belfast has not been dependent recently on a single large employer. Years ago, chicken farming was the big industry, and its byproducts polluted local waterways and made the harbor stink. But the chicken plants disappeared in the 1980s, and ever since Belfast has worked to attract more benign companies.

MBNA, once a leading credit card processing company, brought roughly 4,000 jobs to town in the 1990s. It was purchased in 2006 by Bank of America, which gradually moved many of the jobs to Atlanta but remains a significant employer, with 800 employees in the Belfast area. Front Street Shipyard, established in 2011, is another major employer with a yacht yard, marina and storage facility serving the needs of vessels ranging from small recreational boats to commercial vessels and superyachts. Aetna Health is another major employer, with more than 1,000 workers in the Belfast area.

These big businesses have rescued Belfast from the desolation of the chicken days, and have brought in their wake restaurants and small shops that attract a healthy tourist trade to the scenic town. Over the years, it seems, the town has developed an ethic, or a set of values, that may be at odds with the large-scale industrial ambitions of the salmon farming promoters.

The Opposition

That, at least, is the view of one key leader of the opposition, Eleanor Daniels. She is a committed environmentalist who has spent 25 years building up The Green Store, whose website says its “mission[is] to promote personal and planetary well-being, [and] to provide simple, practical products to help people live an environmentally sustainable lifestyle.” The store has become a storied local institution, as the Bangor Daily News observed in April.

In a recent interview, Daniels described Belfast as a community that promotes “small food economies, with small farms, biodiverse farms, and that has a large arts community and a thriving downtown with many owner-operated businesses.”

A walk through its historic downtown, and along its waterfront, confirms the small-town, historic feel Daniels said contributes to the town’s “branding” as a friendly destination.

Belfast has a history of fighting off proposals that might threaten this image: in the 1950s, it voted to fund a bypass that rerouted busy, north-south Route 1 away from the center of town, and in the 1990s it nixed a proposed Walmart by passing a referendum to limit the size of big box stores.

Daniels has started up a resistance movement called Local Citizens for SMART Growth: Salmon Farm. It has a list-serve with 250 subscribers, Daniels said. The group has been holding meetings, the last one of which, on July 8, developed a long list of actions to generate opposition to the salmon farm. Daniels and a co-plaintiff on July 11 filed a lawsuit in Waldo County Superior Court against the city of Belfast, the Belfast Water District and Nordic Aquafarms on procedural and other grounds.

Daniels ran through a litany of problems her group sees with the salmon farming facility. It will be a major consumer of fresh water, supplied by aquifers that might be at risk, opponents say. In a paper on the topic they note that Maine is one of only three states that has not repealed the 19th century “absolute dominion rule,” which allows major water users to draw as much water as they like without regard to effects on others using the aquifer.

The facility will also be a major user of energy, Daniels notes. Nordic Aquafarms has pledged to install solar panels to help power its operations, but Daniels has calculated that they will meet at most 10 percent of the energy needs, implying demands on the grid that would aggravate the state’s carbon footprint.

The plant will also be uncomfortably close to the Little River Trail. A 250-foot buffer zone between the river and the plant will preserve the walking trail and trees along it, but the issue remains controversial enough to have drawn a reporter for local publication The Republican Journal to examine the setbacks’ adequacy with an energetic video report.

Daniels has compiled four documents outlining the problems opponents see.

What seems now to be a small group of activist citizens could perhaps swing public opinion against the wishes of the Belfast city council and city manager. Formal permitting processes won’t begin until the fall.

Supporters and the Maine ‘Brand’

But it seems an uphill battle at the moment. The state’s two U.S. Senators and Gov. Paul LePage have been behind the onshore farming industry, among other proponents.

Onshore fish farming enjoys the support of the Atlantic Salmon Federation, which is dedicated to the conservation, protection and restoration of wild Atlantic salmon and the environment on which they depend. Andrew Goode, a vice president of the federation, recently posted a statement in support of the Bucksport and Belfast initiatives and their “race...to bring larger volumes of environmentally friendly, U.S.-based salmon to market.”

Goode noted that his group years ago expressed opposition to offshore salmon farming, saying that “wild salmon stocks and the health of our coast bays were being threatened by a sea-cage industry plagued by large escapes, increased densities of sea lice and diseases such as infectious salmon anemia.” Problems still remain with offshore salmon pens, he wrote. “Our conclusion,” he said, “is that land-based salmon farming is an innovative, sustainable alternative to sea-cage aquaculture. There is little if any impact on wild species or the environment, and salmon are not stressed by predators and parasites.”

The Bangor Daily News reprinted Goode’s statement on its June 12 op-ed page.

Support has also come from the Maine Lobster Marketing Collaborative, whose executive director, Matt Jacobson, was one of the experts recruited to speak at the most recent public information session in Belfast. In an interview with Route Fifty, Jacobson cited pollution from sea-cage farming as of concern to his industry, and also said that onshore salmon farming should help with the economics of lobstering.

The trimmings from onshore-farmed salmon will be free of sea lice and other problems, and thus should be perfect as bait for lobster traps, unlike the trimmings from sea-cage salmon. Lobstermen have large fixed costs—their boats, traps and other equipment, and two large variable costs: fuel and bait. Bait prices have gone through the roof of late, and the salmon scraps could end up costing half to a third of current levels, Jacobson said.

The onshore farm-raised salmon should benefit from a made-in-Maine label, Jacobson said. “People want to know that their fish is safe and raised in a clean environment,” he observed, and of course imports are unlikely to be as fresh as salmon produced close to and for major East Coast markets. The lobster industry, as well as retailers like L.L.Bean and Stonewall Kitchen, all play up their association with the Pine Tree State.

There’s a romance about Maine and the Maine brand,” Jacobson concludes.

Timothy B. Clark is Editor-at-Large at Government Executive's Route Fifty.

NEXT STORY: California Isn’t Expecting Policy Changes Under the New EPA Head