California’s Record on Climate Change Is a Stark Rebuttal to Trump

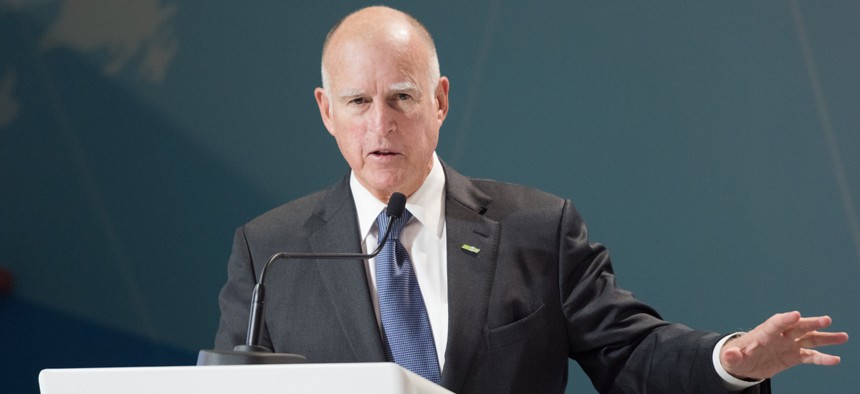

California Gov. Jerry Brown speaking at the 2015 United Nations conference on climate change near Paris. Shutterstock

Connecting state and local government leaders

Governor Jerry Brown is pushing the boundaries of what a single state can do to combat the threat, which grows more tangible with each record wildfire and hurricane.

It’s just a coincidence that as another hurricane turbocharged by unusually warm waters slams into the East Coast, California Governor Jerry Brown is convening a global summit on fighting climate change on the West Coast. But it’s still revealing.

On climate, Brown, a former Jesuit seminarian, has become America’s most insistent apostle for action, the antithesis to President Donald Trump. While Trump is systematically dismantling any federal response to the challenge, Brown’s California is pushing the envelope on what a single state can do to combat what he recently called “the existential threat of climate change.” That threat is growing more tangible seemingly by the week, measured in risks from record wildfires and hurricanes, like the approaching Florence, that draw more destructive power from ocean waters warming as the climate shifts.

Brown, now 80 years old, has been innovating on climate, energy, and the environment for a very long time. During his first term as California governor, back in the mid-1970s, he faced pressure to approve a new nuclear power plant to close a projected gap between the state’s electricity demand and supply. On the advice of Art Rosenfeld, a brilliant particle physicist serving on the state’s then-new energy commission, Brown instead imposed the nation’s first energy-efficiency standards for refrigerators and freezers (followed quickly by rules for air conditioners). That reduced projected demand enough that Brown didn’t need to authorize the nuclear plant.

That choice marked a turning point for California. Under Democratic and Republican governors in the decades since, the state has approved pace-setting policies to require utilities to generate more of their electricity from renewable sources like solar and wind, promote electric vehicles and lower-carbon fuels, encourage conservation by “decoupling” utility profits from the amount of power they sell, and reduce total carbon emissions by 2020 to their level in 1990.

Brown is now finishing his fourth and final term as governor with a flourish. (He was elected in 2010 and 2014 after initially serving from 1975 through 1982.) Earlier this summer, the state announced it had met its 2020 carbon-reduction goal four years early. (He’s already signed legislation mandating another 40 percent reduction by 2030.) This week, Brown signed breakthrough legislation—authored by Kevin de Leon, the state Senate Democratic leader who is challenging Dianne Feinstein for a U.S. Senate seat—that commits the state to generating all of its electricity from carbon-free sources by 2045. He also signed a bill that attempts to block Trump’s plan opening six areas off the California coast to offshore oil drilling. And beginning Wednesday, he’s hosting government, business, and grassroots activists from around the world for a climate summit in San Francisco.

“We have a real program here that’s viable, difficult, but it’s very practical [and] very realizable,” Brown told me in an interview this week. “This is not about trying to get on a horse and flaunt whatever achievements we’ve got [in California]. We’ve got too far to go to be complacent or look backward.”

Yet looking backward is one way California can point the way forward: As Trump and his allies portray climate action as an economic threat, California’s record remains perhaps the most powerful rebuttal. “California is showing that climate policy can be … compatible with economic growth,” says Ann Carlson, a law professor at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Next 10, a nonprofit San Francisco–based research group, recently quantified the gains in its annual California Green Innovation Index report. From 2006 through 2016, the group reported, the state’s economy grew 16 percent and its population expanded by more than 9 percent. Yet over that same period, California cut its carbon emissions by 11 percent. Even as it squeezed emissions, California passed the United Kingdom to become the world’s fifth-largest economy.

California has succeeded most in transforming its electric-power sector. Reflecting its commitment to efficiency, the state’s per-person electricity use is down more than 7 percent since 1990 (while it’s increased more than 8 percent in the rest of America). Solar, wind, geothermal, and other renewables now account for about 30 percent of that electricity’s generation; the bill Brown signed this week commits the state to doubling that share by 2030, en route to carbon-free power by 2045. “California is showing that the transition can happen faster and cheaper than anyone thought possible,” Carlson said.

But transportation, which accounts for two-fifths of the state’s carbon emissions, has proved much tougher. Though down nearly 10 percent since 2000, those emissions have increased in each of the past four years as Californians drive more miles (partly because the state’s housing-affordability crunch is forcing many people to live further from their work). Compounding the challenge, public-transportation ridership has fallen in four of the state’s five largest metro areas.

Brown is betting heavily on electric vehicles to close the gap: He’s set a goal to have 1.5 million of them on the road by 2025, with 5 million on the road by 2030, up from about 400,000 today. But the state has 32 million vehicles in operation, which slows the pace of change. “We have come a long way, but given the fact that we have so much embedded infrastructure, we [will] need a lot of help from the federal government and we need the auto companies to step up,” Brown says.

Instead, the federal government is fighting California’s efforts. The Trump administration has proposed repealing the improvements in automotive mileage that former President Barack Obama mandated on auto companies and revoking the waiver Obama granted allowing California to set its own tougher standards (which 13 other states have adopted, too). Simultaneously, Trump has moved to eviscerate Obama’s plan for reducing carbon emissions from power plants. This week, Trump also proposed revoking Obama’s regulation limiting leaks of methane, another powerful greenhouse gas—a decision Brown calls “a disgrace bordering on criminality.”

Brown expressed optimism that California and its allies can block Trump’s proposed climate rollbacks in court through 2020. But Brown conceded that “if he takes a second term … all bets are off.”

In the transition to a lower-carbon world that reduces the risk of catastrophic climate change, California has made landmark gains, many of which reflect Brown’s commitments stretching back decades. But meeting its 2030 carbon goals will require the state to reduce emissions more than three times as fast as it has already. Even as he convenes a global array of like-minded allies this week, Brown has no illusions of how hard that will be, especially under a president who refuses to act—even as the signs of growing danger are literally blowing in the (hurricane) wind around him. “Sooner rather than later we need an ally in the White House,” Brown says, “not an enemy."

Ronald Brownstein is Atlantic Media's editorial director for strategic partnerships. This article was originally published in The Atlantic.

NEXT STORY: California Legislation Would Mandate List of Quake-Vulnerable Buildings