The Homeless Get Sick; ‘Street Medicine’ Is There for Them

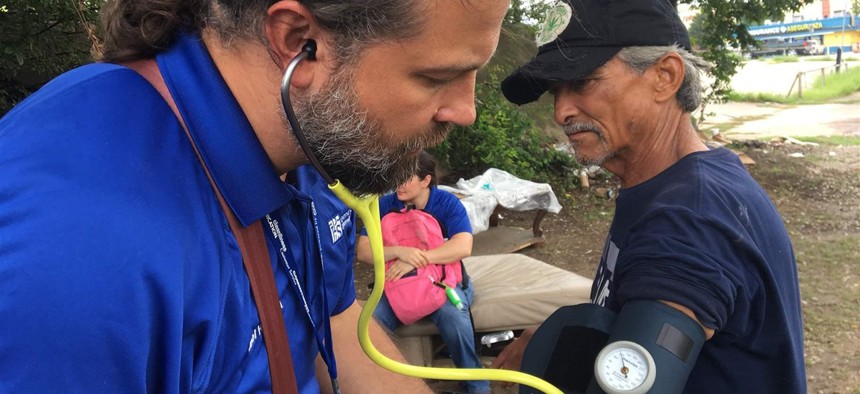

Physician assistant Joel Hunt treats Raul Reyes, 59, at a homeless encampment outside of downtown Fort Worth, Texas. The Pew Charitable Trusts

“Street medicine,” which had only a few resolute practitioners when it got its start in the mid-1980s, has surged within the past decade, growing into a network of programs in over 85 cities and in 15 countries.

This article was originally published by Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, and was written by David Montgomery.

FORT WORTH, Texas — Toting a huge olive-green backpack stuffed with medical supplies, physician assistant Joel Hunt pushes through a dense cluster of woods less than two miles from downtown Fort Worth. He approaches a suspended tarp that serves as a makeshift tent, peeking inside at an elderly woman who was evicted from her home nearly eight months ago.

“So how have you been doing?” Hunt asks. The woman, who is lying on her back, warms up to Hunt’s gentle questioning. She says she is out of medicine for her back pain, and was “kicked out” of her residence in January. Hunt invites her to his clinic for a back-pain referral, then extends his hand in a fist-bump gesture. The woman reaches out and pats his wrist.

“Honestly, her biggest issue that we need to address is getting her out from underneath a tarp by the railroad tracks,” said Hunt, a stocky 41-year-old with a salt-and-pepper beard and dark brown hair tied in a ponytail.

“This is not a friendly place. Some bad actors come through here, and they don’t necessarily have to have a reason to hurt you. It’s a hard life.”

That description—“a hard life”—could easily apply to the entire caseload of homeless patients served by the still-emerging field of street medicine.

“Street medicine,” which had only a few resolute practitioners when it got its start in the mid-1980s, has surged within the past decade, growing into a network of programs in over 85 cities and in 15 countries. In the United States, street medicine programs are operating in more than 20 states and at least 45 cities, including New York, Chicago, Atlanta, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, Detroit and Washington, D.C.

Advocates attribute much of the growth to organized efforts by street medicine supporters to expand awareness and create new programs. The first street medicine symposium was held in 2005 in Pittsburgh, followed by the creation of the Street Medicine Institute four years later. A 2017 symposium in Allentown, Pennsylvania, drew more than 500 international participants, compared with a handful at the Pittsburgh gathering.

So-called point-in-time estimates by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development placed the number of homeless people at 553,742 in 2017. Two-thirds, or 360,867, were in emergency shelters or transitional housing. The remaining third, or 192,875, were in unsheltered locations—making them most vulnerable to threatening diseases and physical abuse.

Homelessness declined by 14 percent—93,516 people—over a 10-year period starting in 2007, but it increased by 1 percent between 2016 and 2017, according to HUD.

In some areas of the country, such as California and Hawaii, soaring housing prices are fueling a more rapid increase. One recent study found that eight of the 10 states with the highest rates of homelessness also were among the 10 states with the highest median housing prices.

Hunt’s Fort Worth-based street medicine program, sponsored by the JPS Health Network, Tarrant County’s safety-net public health provider, is one of the few in the country to be operated by a tax-funded health system instead of a nonprofit.

A primary goal of the JPS program is to cut down on emergency room visits by the homeless. Some patients treated by Hunt’s team visit the emergency room more than 50 times a year, according to JPS. Public and private hospitals alike are prohibited by federal law from turning away patients.

“Homelessness is hazardous to one’s health, and homelessness kills,” said G. Robert “Bobby” Watts, CEO of the Nashville-based National Health Care for the Homeless Council, which advocates for policies to combat homelessness, including comprehensive health care and expanded access to housing.

Lacking shelter, showers and adequate nutrition, homeless people living outdoors are more likely to suffer from a range of illnesses, including high blood pressure, diabetes, frostbite, heat stroke and other maladies. Many have mental illness and addiction problems.

In Search of Patients

Street medicine practitioners must search for their patients, often traveling into high-crime neighborhoods and secluded homeless camps in wooded vacant lots and alongside rivers and creeks. Many of those who take up the challenge are often driven by a deep-seated commitment to serve the less fortunate.

After addressing immediate health needs, street medicine teams try to connect the homeless with follow-up services through clinics and nonprofits. The goal is to get the homeless into transitional shelter as quickly as possible, and then to connect them with jobs and permanent housing.

“When you devote the resources, especially housing resources, you can help end homelessness,” Watts said.

An early practitioner, Dr. Jim Withers, used to dress in tattered clothes and rub dirt in his hair to blend in with his homeless patients on the sidewalks of Pittsburgh in the early 1990s. Withers, 60, who serves as medical director of Pittsburgh Mercy’s Operation Safety Net, traces the roots of his involvement to his childhood, when he often accompanied his physician father on house calls.

“There was just something about those house calls that never left me,” he recalled. “I really wanted to get out of the hospital and really embed myself with people who were not being served.

“When I first started going out, I was just amazed with the number of people tucked into nooks and crannies and along river banks and how many had medical problems that weren’t receiving any care.”

Withers, along with James O’Connell, who founded the Boston Health Care for the Homeless program in 1985, is one of the physicians whose legendary stature in the homeless medicine world influenced Hunt, a former Army medic from Houston.

Hunt’s service in the Army from 1998 to 2004 included being assigned to an unconventional warfare surgical team in Colombia to support the 7th Special Forces Group, which was in the country to assist and train the Colombian Army in counter-insurgency operations. Hunt described it as a “bare-bones operation” to treat U.S. and Colombian Army personnel, as well as civilians in danger of losing life, limb or eyesight.

After getting his master’s degree as a physician assistant at the University of Utah in 2008, Hunt became medical outreach director for the Fourth Street Clinic in Salt Lake City and started the homeless clinic’s street medicine program in 2009. He was hired to head the Fort Worth outreach team in 2014.

As director of the eight-member JPS Care Connections team, Hunt is based in the JPS Medical Home clinic at True Worth Place, a resource center located near Interstate 35 in the heart of Fort Worth’s homeless community. It is surrounded by four homeless shelters and, on any given day, serves as a magnet for throngs of homeless people who begin arriving early in the morning.

Hunt’s team includes five community health workers, a social worker and a nurse. Hunt sees patients at the clinic, but he mostly ventures onto the streets to search for homeless patients.

“We’re not trying to be an ambulance that sees you once and leaves and never comes back,” Hunt said as he set out earlier this month. “We try to keep a handle on the folks that we do see. It’s easier said than done.”

Dignity and Hope

His first stop was an overgrown vacant lot across the street from a convenience store. Several men and a woman sat under a large tree, greeting Hunt and his colleagues, behavioral science specialist Candace Barton and community health worker Rachel Stovall, with an obvious familiarity.

Discarded remnants of middle-class life, including an old coffee table and part of a sectional couch recovered from a curb, served as furnishings for the outdoor residents. As Hunt took their blood pressure and checked for other vital signs, some talked matter-of-factly about a rootless life and struggles with alcoholism.

Robert “Gizmo” Huerta said he served 15 1/2 years in prison for a motor vehicle burglary before being released in 2008. He’s been living at the encampment for about a year. He wears thrift store clothing, sleeps on cardboard and relies on odd jobs for income. His arms are laced with tattoos from his prison days.

“It’s a lot better than being locked up,” said Huerta, who turned 47 in August. “I’d rather be hungry and homeless than be locked up.”

Brandi Jones, 40, brushed back tears as Hunt checked her hands, took her blood pressure and asked about her overall health. “Last night, I could feel my whole heart beat,” she said, telling the PA that she felt “more depressed than anxious.” After Hunt asked what was worrying her, she told him, “Stupid stuff.”

“It’s not stupid if it’s making you anxious,” Hunt told her.

Jones, who was born in Oklahoma, said she spent her early years in foster care. “It’s a long story and I really couldn’t get into it.” She said she is still married to her husband of 23 years, but hasn’t seen him or her children since around 2010.

Raul Reyes, 59, originally from El Paso, said he has been homeless for more than a year, since losing a $732 monthly federal disability payment because of what he described as a paperwork issue. He said he was plagued by back problems and high blood pressure, which Hunt said could be helped with medicine. Team members also advised Reyes that he could possibly get the clinic to help restore his disability payments.

Hunt’s backpack is filled with dressings, wound care kits, iodine, toenail trimming equipment, colon cancer screening cards, condoms, suture removal kits and other items. A smaller yellow bag that he carries over his shoulder contains a blood pressure kit, stethoscope, thermometer and one of his “most powerful” tools, a small laptop that can link him to health network data.

The father of four said street medicine sends a powerful message to the people it serves.

“They’re not talked about in a fond, kind of normal, humanizing way,” he said. “Having somebody check in on them because they’re human goes a long way to adding dignity, adding hope.”