Testing Out Faster and Flexible Ways to Deploy Homeless Shelters and Services

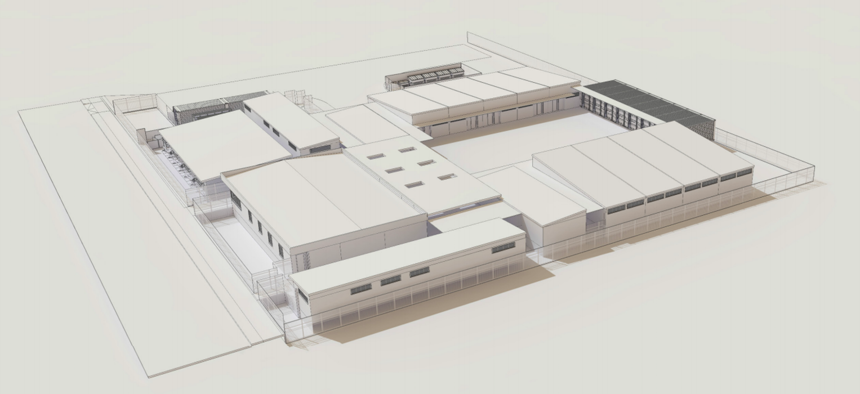

A rendering of a "modular congregate shelter" King County is planning to build on county-owned land in Seattle. Courtesy King County, Wasington

Connecting state and local government leaders

Modular housing pilot projects in King County, Washington aim to create flexible and replicable prototypes of how to expand the number of beds and provide 24/7 case management.

SEATTLE — When marshaling resources to respond to a local homelessness emergency, there can be a lot of roadblocks in deploying badly needed new shelter space and support facilities. Getting necessary approvals and neighborhood resistance can cause various delays, but the actual construction process—whether it involves renovating an existing building or building a new one—can also push back or complicate timelines.

But what if some of those traditional construction delays could be avoided?

The King County government, working with various local cross-sector partners in and around Seattle, recently announced a new pilot project aimed at building new shelter spaces with new types of modular housing that can be delivered much more quickly and assembled in different configurations that also allow 24/7 on-site support services and case management. Two of the pilot locations are scheduled to open by this time next year.

Looking for creative—and in the case of modular housing, flexible—solutions is a necessity in the Seattle area where “we have a tremendous constraint when it comes to land,” King County Executive Dow Constantine told Route Fifty in a recent interview. That’s an understatement in a region where a booming economy, an influx of new residents and limited areas designated to accommodate growth, makes it expensive for governments to acquire new property.

For the first of the three pilot locations, located along Elliott Avenue in Seattle, King County will be using county-owned land to build a “modular congregate shelter” campus featuring nine dormitory units—eight beds per unit—that can house 72 people who are surrounded with 24/7 case management provided by Catholic Community Services. Every unit will come with storage lockers and the campus will include full kitchen, laundry and bathroom facilities. The county is spending $4.5 million on the facility, which includes $2.7 million to purchase the modular units and make improvements to the host site.

There are “different ways to configure use,” Constantine said. And that’s important when delivering services for the homeless.

The Elliott Avenue site will be geared to those with behavioral health needs and people preparing to exit homelessness, including singles, couples and people with pets.

“If we’re able to use land for a limited period to address the need of getting [people] off the street and into long-term stability,” Constantine said, the more likely the region will be to deal with its homelessness crisis and work collaboratively toward a “shared goal of secure housing and self-sufficiency.”

The units at the Elliott Avenue site are designed to last at least 20 years are scheduled to be ready for use in August 2019. But “when the time comes, we can pick them up and move them elsewhere,” Constantine said.

For a second pilot location, King County has partnered with the city of Shoreline, a suburban community north of Seattle, where the county will install 80-100 units of modular housing, including studios and one bedrooms, on a city-owned property. Through a competitive selection process, the Community Psychiatric Clinic will provide services while Catholic Housing Services is serving as a development consultant. The county is tapping $4.5 million in funding from a levy for veterans, seniors and human services for the Shoreline project.

“Shoreline is doing its part to tackle the regional housing crisis. We continue to work with our partners on better and cheaper ways to provide housing for those in our community and in our region who are most in need,” Shoreline Mayor Will Hall said in the county’s announcement.

King County will test a third configuration, a cluster of stacked “modular micro dwelling units” designed for a more urban setting that also allows enough room on-site for 24/7 support services, in this case, provided by the Downtown Emergency Service Center.

Although a host site has not yet been identified, the county has ordered 20 prototype units, each one costing approximately $150,000. People with behavioral health needs and those exiting homelessness will be the first applicants, but the configuration is also an option for people in need of affordable housing. The county has committing $3 million to that pilot project, including $1.8 million to purchase the modules, which will feature fire suppression systems plus air conditioning and heating. Like the modular congregate shelter, the micro dwellings are being manufactured by Whitley Evergreen, a Marysville, Washington-based company under a $4.5 million contract with the county. The Washington state government is kicking in $1.5 million, too.

Constantine said the projects are designed to fit into the landscape of the areas neighboring the temporary shelter locations.

King County’s pilot projects are also expected to show their potential temporary use on privately owned land, like a vacant lot that a developer may use in the future to develop a new apartment building or a faith-based organization looking to leverage its property to serve the needs of the homeless.

Constantine said King County’s new pilot projects will bring an “expanded palette of options” for the local response and when they’re up and running next year, will also provide local officials in King County with models for how homeless shelters and services can be configured and deployed efficiently when they’re needed. Each pilot location has certain things that will be used to test things like the speed and reliability of construction and ability to be replicated on other sites.

And while disaster recovery wasn’t necessarily designed as part of the testing, King County’s modular housing pilot projects will provide important insights into the potential of deploying similar temporary housing clusters following the region’s next major earthquake, whether that’s the dreaded future magnitude 9.0 Cascadia Subduction Zone megaquake or something more local, like a magnitude 7.0 quake along the Seattle Fault, both scenarios that are expected to create an acute regional housing crisis and displacement as infrastructure is rebuilt.

Constantine acknowledged that following the Seattle region’s next major disaster, when tens of thousands of people will suddenly find themselves homeless, “the simple issue of housing will be daunting” for a recovering region. “We have to be ready to house people.”

Successfully providing homeless services in the near term will, hopefully, make tackling that looming and especially difficult challenge somewhat easier.

Michael Grass is Executive Editor of Government Executive’s Route Fifty and is based in Seattle.

NEXT STORY: Back-to-School Time Means Kids Are Back to Breathing Their Parents’ Auto Exhaust