Forecasting How Policy Changes Could Affect Prison Populations

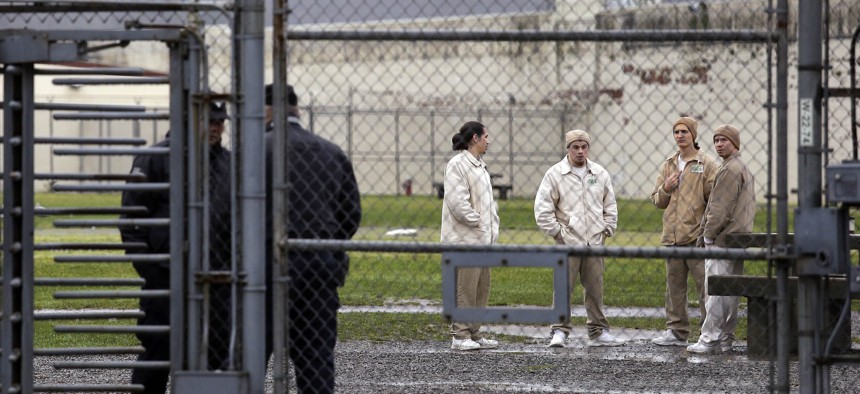

In this file photo taken Jan. 28, 2016, inmates mingle in a recreation yard in view of guards, left, at the Monroe Correctional Complex in Monroe, Wash. AP Photo/Elaine Thompson, File

A new online tool offers a look at how choices by states could raise or lower the number of people behind bars.

Estimates of how different policy changes could expand or reduce state prison populations are now available using a new online tool.

The Urban Institute released its Prison Population Forecaster on Wednesday. It lets people adjust prison admissions and sentence lengths for various types of crimes, and to see how these changes affect the number of people expected to be incarcerated in a state during future years.

It’s also possible to model what the different policy choices could mean in terms of racial disparities and costs.

“There’s a lot of, I think, excitement about the idea of correctional reform. But there’s also a lot of misinformation,” Bryce Peterson, an Urban Institute researcher who worked on the project, said by phone. “The tool here is to provide more context and more evidence.”

Peterson noted, for instance, that a common perception is that it is possible to dramatically reduce prison populations by focusing mainly on lower-level, or non-violent, offenders.

But the tool shows that this is not necessarily the case.

“What you might find is that it’s going to be really difficult to make substantial changes in most states, in their prison populations, if you don’t address more serious or violent crimes,” Peterson said, noting that neither he nor the Urban Institute are advocating for this.

That said, something else he pointed out is that the tool demonstrates how there is no one-size-fits-all approach for states seeking to cut down on the number of people in their prisons.

In every state, cutting the prison population, even by a significant amount, does little to reduce the proportion of the prison population made up of people of color, and in some cases would worsen the current racial disparities, according to the Urban Institute.

About 2 million people are detained in the U.S. criminal justice system, held in 1,719 state prisons, 102 federal prisons, 1,852 juvenile correctional facilities, 3,163 local jails and other facilities, such as Indian country jails and military prisons, according to a March report from the Prison Policy Initiative.

About 1.3 million of those people are convicted of crimes and held in state prisons, the report says.

The Vera Institute of Justice published figures last year showing that combined state prison expenditures across 45 states totaled nearly $43 billion in 2015.

In May, the U.S. House passed bipartisan legislation, the First Step Act, which includes changes to federal prison policies—such as bolstering educational and vocational programs—that are geared heavily toward rehabilitating prisoners and helping them transition back into society.

The bill did not include alterations to minimum sentencing requirements that some moderate and left-leaning lawmakers want to see. It also focuses on federal, not state, prisons.

Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Chuck Grassley, an Iowa Republican, said last month that President Trump had voiced support in an Aug. 23 meeting for prioritizing prison and sentencing reform soon after the November elections. Grassley also said that Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell indicated an openness to bringing up legislation on the issue this year.

The data that provide the foundation for the Urban Institute tool are reported by states to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Five states—Arkansas, Connecticut, Hawaii, Vermont and Idaho—are not included in the forecaster because they didn’t provide adequate data.

Funding for the project came from the American Civil Liberties Union, which is working on state-specific blueprints for prison reform.

Peterson described the results the tool produces as a rough assessment of what a policy change might do and said that the nature of such forecasts is that they are not entirely accurate.

But he also said that researchers checked the tool’s results against models that individual states produced for forecasting prison populations and found the results to be similar.

The forecaster is based on a similar, earlier tool that offered a more stripped down set of options for adjusting policies and only featured 15 states. Peterson said there are plans to update the data in the latest version as time goes on, but that it could depend on funding.

Bill Lucia is a Senior Reporter for Government Executive's Route Fifty and is based in Washington, D.C.

NEXT STORY: California Just Replaced Cash Bail With Algorithms