A DNA Database With 2% of The Population Can Be Used to Find Almost Anyone

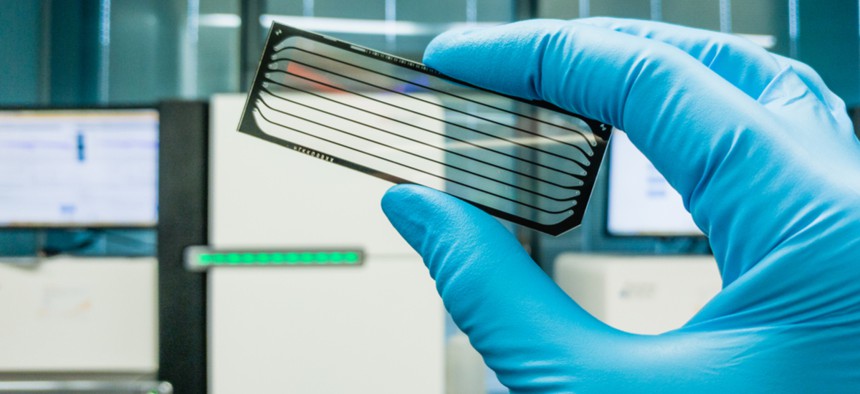

A new study found that a genetic database needs to cover only 2% of the target population to provide a third-cousin match to nearly any person. Shutterstock

Familial DNA testing has opened up a powerful new technique for identifying people.

Joseph James DeAngelo, who authorities believe to be the “Golden State Killer” responsible for 12 homicides and 51 rapes across California between 1974 and 1986, was arrested in April at the age of 72 at a point when the case was so old that many believed the killer would never be caught. DeAngelo was arrested using some pretty novel DNA techniques.

Investigators used DNA recovered from one of the crime scenes to find the suspect’s great-great-great grandparents, who lived in the early 1800s. A team of five created about 25 family trees containing thousands of relatives using available public data—using “census records, newspaper obituaries, gravesite locaters, and police and commercial databases,” according to the Washington Post—from that era until now. One branch included DeAngelo.

The technique they used is called familial DNA testing. In past forms of DNA testing, a suspect were caught if their DNA was a perfect match to samples found at the crime scene. Familial DNA testing looks for partial matches, which can provide leads to make arrests. A new piece of research published in Science shows just how powerful that technique can be.

Researchers from Columbia University, the New York Genome Center, and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem conducted a statistical analysis of 1.28 million individuals, mostly from the MyHeritage database. They concluded that a genetic database needs to cover only 2% of the target population to provide a third-cousin match to nearly any person. In the case of the US, that would equate to a database of 3 million US individuals of European descent, which they believe is quite likely to exist soon given the increasing popularity of at-home genetic testing kits and ancestral databases.

“We project that about 60% of the searches for individuals of European-descent will result in a third cousin or closer match, which can allow their identification using demographic identifiers,” the researchers concluded. “Moreover, the technique could implicate nearly any US-individual of European-descent in the near future.”

While this might be wonderful to help catch killers in cold cases—as familial DNA testing already seems to be doing—the researchers noted that there are some strong ethical issues that need to be considered.

“While policymakers and the general public may be in favor of such enhanced forensic capabilities for solving crimes, it relies on databases and services that are open to everyone,” they wrote. “Thus, the same technique could also be exploited for harmful purposes, such as re-identification of research subjects from their genetic data.”

There is a wealth of data about each of us online already, publicly available for all to see. Perhaps we should think hard about whether we want our actual DNA to be a part of that.

Kabir Chibber is a business editor at Quartz, which originally published this article.

NEXT STORY: ‘Marsy’s Law’ Protections for Crime Victims Sound Great, but Could Cause Problems