It’s Too Soon to Celebrate the End of the Opioid Epidemic

Federal stats show that drug-overdose deaths are down. Shutterstock

Drug-overdose deaths have been down for six months, but it’s too early to know whether the good news will continue.

The good news is that deaths from drug overdoses in America have been falling slightly for the past six months, granting a reprieve from what seemed like an opioid epidemic with no end in sight. The bad news is that no one knows why, or if this trend will continue.

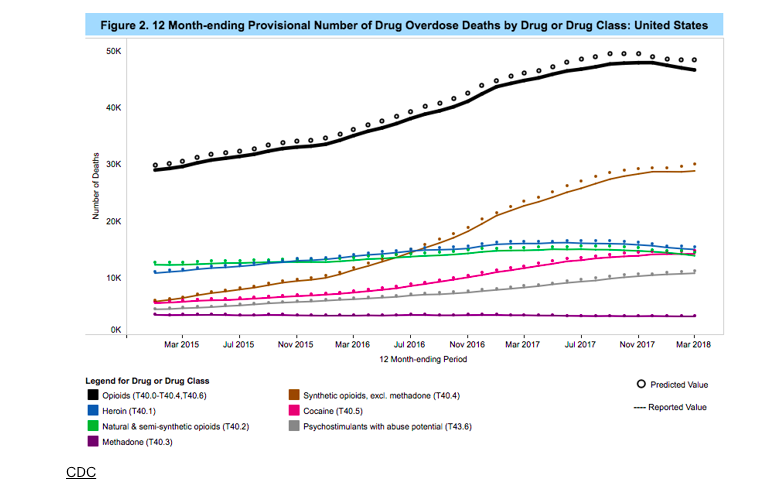

Preliminary figures reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention this week show that compared with the 12 months ending September 2017, opioid deaths are down 2.8 percent in the 12 months that ended March 2018, reflecting about 2,000 fewer people who have died of a drug overdose. But, as the Associated Press points out, the final numbers for this year won’t be available until the end of next year, so we don’t know if this downward trend has continued.

At an event this week, Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar called the decline not the end of the epidemic, but “perhaps the end of the beginning.”

While we don’t know why deaths have begun to fall, experts say there are a few likely reasons. Doctors are prescribing fewer painkillers. More states are making naloxone, which reverses opioid overdoses, widely available. And it’s possible that more addicts have started medication-assisted therapies like buprenorphine, which is how France solved its own opioid epidemic years ago. Indeed, the states with the biggest declines in overdose deaths were those like Vermont that have used evidence-based, comprehensive approaches to tackling opioid addiction.

Fentanyl and heroin addicts might also have become more careful about how they consume the drugs. “It is also plausible that there are behavioral adaptations by folks that use heroin that are leading to safer fentanyl use,” says Daniel Ciccarone, a professor of family and community medicine at the University of California at San Francisco. “These include sampling the drugs before consuming, going slower, getting information about potency from others.”

Still, it’s possible this is a “false dawn,” as Keith Humphreys, an addiction expert at Stanford University, put it to me. “Opioid-overdose deaths did not increase from 2011 to 2012, and many people declared that the tide was turning. But in 2013, they began racing up again,” he said. Deaths from synthetic opioids like fentanyl are still rising, as are those from methamphetamines.

In other words, we won’t know if this downturn in deaths is “real” for a few years. But “even if this is real, even if we are finally cresting, it’s hard to celebrate,” says Andrew Kolodny, a psychiatrist who studies addiction at Brandeis University. The lower numbers still reflect about 70,000 people dying of a drug overdose every year. And that’s not to mention all the babies born in withdrawal from heroin, all the kids in foster care, and all the people who still can’t get treatment and are using every day.

“There’s a lot more to this problem than just the deaths,” Kolodny says.

Olga Khazan is a staff writer at The Atlantic, where this article was originally published.

NEXT STORY: DHS Preps Extra Cyber Support for States with Close Midterm Races