This State Could Outlaw Ballot Collection Efforts

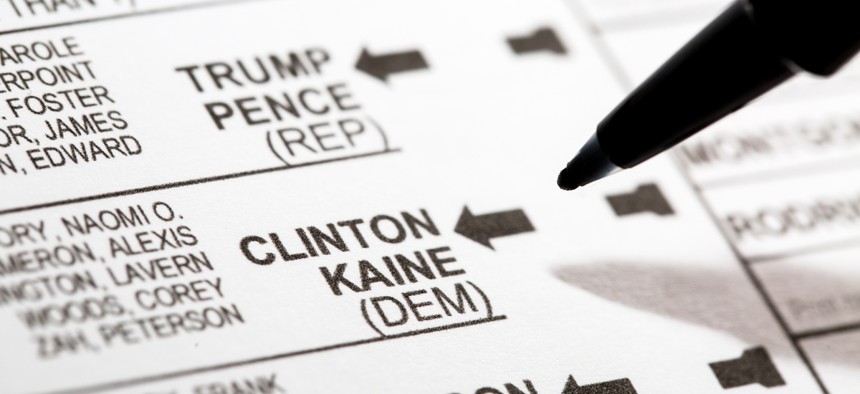

A proposal before voters in Montana this November could make it harder for people to vote absentee and have somebody else deliver their ballot. Shutterstock

In Montana, many voters, including Native Americans, rely on volunteers to collect and deliver their absentee ballots. But a referendum next month would end the practice.

This article was originally published by Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, and was written by Matt Vasilogambros.

In the months leading up to this week’s registration deadline, Renee LaPlant has registered voters in the Blackfeet Nation in northwest Montana wherever she can: at grocery stores, public events or even at people’s homes on the Native American reservation. Each time she registers new voters, she asks whether they will want her to collect their completed ballot and turn it in to their local county clerk and recorder’s office or courthouse.

For many of these would-be voters, simple things such as getting stamps, fixing a flat tire or filling up enough gas to make it across this reservation—which is larger than Delaware—may be difficult, since more than a third of Blackfeet live below the poverty line.

“People are focused on keeping their lights on, keeping their heat on, and voting can take up their time,” said LaPlant, an organizer for Western Native Voice, a local nonpartisan social justice group. “If you’re worried about it, I can take care of that process for them.”

Western Native Voice has collected hundreds of absentee ballots statewide every election year in tribal areas, said Alissa Snow, the group’s field director. But it’s not just groups like hers that collect ballots. Voters across the state, she said, will at times trust others to deliver their ballots, especially voters with disabilities and who live in rural areas.

This practice, however, could end if a legislative referendum on the November ballot passes, making it a crime for groups to collect absentee ballots. Montana would become one of 16 states to regulate ballot collecting in some way—from outright bans to defining who can or cannot turn in another person’s ballot, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

As more states and counties adopt vote-by-mail systems and absentee voting, there are more ballots outside the control of election officials, said Wendy Underhill, NCSL’s director of elections and redistricting. Measures like banning “ballot harvesting” are among the many that lawmakers now consider fine-tuning procedures, Underhill said. But the debate over such bans has grown heated.

Matthew Harper, a California Republican assemblyman who authored a proposed ban on ballot harvesting that died in committee earlier this year, said he’s not concerned about family members returning absentee ballots. He is, however, concerned that groups like labor unions might collect unsealed ballots or intimidate voters into voting a certain way.

“The way I see it, it turns all elections into a union card-check election,” Harper said. “They might go house to house, person to person, and there’s no secret ballot. They can see if you voted the right way.”

Ballot harvesting took center stage in at least one election this year: in Texas, where a March lawsuit claimed a local election judge was paid to gather ballots in a judicial election decided by one vote. A special election followed in July, which the candidate who had sued, Tracy Booker Gray, won by more than 400 votes.

Bans on ballot collection have stood up in federal court. In 2016, Arizona passed a law banning anyone except a family member, household member or caregiver from returning another person’s ballot. People who pick up ballots in violation of the law could face a $150,000 fine and a year in prison.

State Democrats opposing the ban said the law was an attempt to keep some voters from the polls, especially Latinos who rely on friends and neighbors to help them through the voting process, according to The Arizona Republic. Last month, however, a federal appeals court upheld the ban, finding Republicans did not need to prove claims that ballot collecting leads to voter fraud.

‘It Matters to Vote’

In 2012, a problem with ballot harvesting led to voter fraud in Arizona, said Patty Hansen, the recorder in Coconino County, Arizona. An advocacy group not affiliated with a political campaign in Flagstaff, Arizona, had staff members pretend to be from the county’s election office when they collected ballots, she said. But when she found out, she asked the group to stop the practice and warned that she would report them to the county attorney if they repeated it.

Hansen said she doesn’t support groups collecting ballots, but she thinks the law is not enforceable.

“I can’t understand why anyone would give their ballot to a stranger,” she said. “But if someone brings 100 ballots to my counter, I’m going to accept them. I’m not going to disenfranchise 100 people’s votes. I have no enforcement authority; I’m not going to say I’m going to arrest you.”

Montana’s referendum narrowly made it on the ballot by a thin vote in the Legislature with the support of most Republicans and only one Democrat. Seth Berglee, a Republican state representative, said the measure would prevent organizations and political parties from intimidating voters, while still allowing family and friends to help a voter in need.

“We had some issues in Montana during the last election where people were going door to door, asking who they voted for and picking up their ballots,” he said, referring to 2016 news reports. “People called the police. That raises issues with voter integrity. I don’t think wholesale ballot collection is the way to go.”

While Montana’s measure bans the collection of ballots, it has several exceptions, including for acquaintances, caregivers, family members and household members. But according to Jordan Thompson, an attorney for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, those exceptions aren’t enough.

“Our definition of family is a lot broader than the Western definition of families,” he said. “Just in the way our communities are structured, how our families are so extended, it doesn’t make sense. This could stand in the way of the Native voice getting to the ballot box.”

It’s already a challenge to get Native Americans to participate in the political process, he said. Indeed, American Indians and Alaska Natives vote less than other racial or ethnic groups, in part, as Stateline reported, because of strict state voter ID laws and county policies that may negatively affect ballot access.

Just this week, the U.S. Supreme Court allowed a strict voter ID law in North Dakota to go into effect. Critics claim the Republican-passed law targeted Native American voters who played a pivotal role in electing Democratic Sen. Heidi Heitkamp in 2012. This could make her reelection effort this November even harder.

It’s unclear whether the Montana referendum will pass. There has not been any major polling on the issue. Many Democrats have criticized it. Roy Loewenstein, the communications director for the Montana Democratic Party, called it “a blatant attempt at voter suppression by a small group of out-of-touch politicians.”

Even some Montana Republicans, who in other states have largely backed these bans, think the referendum is unnecessary. Republican state Rep. Geraldine Custer, who voted against putting the referendum on the ballot, said proponents of the referendum are “trying to put a black eye on the election” by claiming there’s voter fraud.

“This is about neighbor helping neighbor,” said Custer, who served as the Rosebud County clerk and recorder for nearly 40 years. “This is what rural America is all about. If you get cancer and can’t run your cropping equipment, your neighbor helps out.”

Forrest Mandeville, another Republican state representative, still supports the legislative referendum, despite concerns from Native Americans about the lack of access to distant post offices and the cost of postage.

“You don’t have to vote by mail if you don’t want to,” Mandeville said. “The big deal is ballot security and making sure there’s a minimal number of hands on the ballot when it gets processed.”

Absentee ballots will be sent to voters across Montana on Oct. 12. For now, LaPlant has her list of 60 people who asked her to pick their ballots up, as she has for the past four years she’s been an organizer at Western Native Voice.

“A lot of them are voting for the first time in their lives because of the issues we’re up against,” she said. “They know it matters to vote.”

She just doesn’t know if she’ll be able to help them again after November.