The Sudden, Shocking Growth of Hurricane Michael

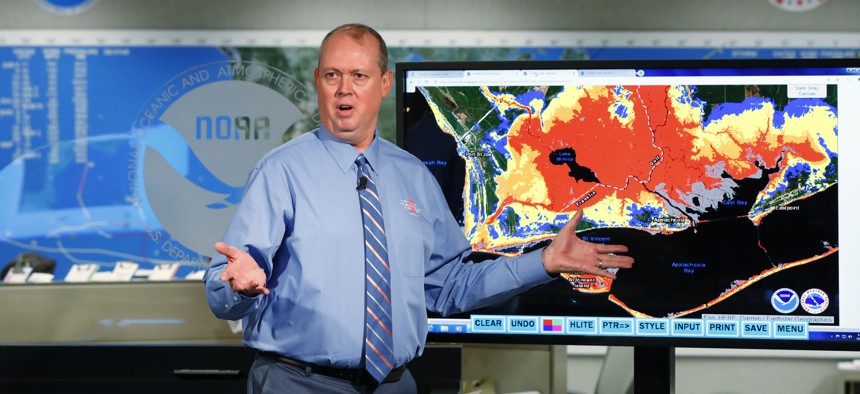

National Hurricane Center director Ken Graham, gestures as he talks about storm surge during a televised update on the status of Hurricane Michael, Tuesday, Oct. 9, 2018, at the Hurricane Center in Miami. Wilfredo Lee / AP Photo

In little more than a day, a Category 1 storm became a “worst-case scenario” Category 4.

The already bad 2018 hurricane season has gotten even worse.

On Wednesday afternoon, Hurricane Michael became the second major storm to make landfall this year. Michael is an incredibly dangerous, history-making storm, bringing catastrophic high winds and deadly storm surge to Florida’s Panhandle. It ranks among the most ferocious land-falling hurricanes in American history.

“THIS IS A WORST CASE SCENARIO for the Florida Panhandle!” said Louis Uccellini, the director of the National Weather Service, in a statement. Officials urged local residents who have not already evacuated to stay inside or find shelter on high ground.

Michael, which will churn across the Southeast over the next several days, has already broken records. As a powerful Category 4 storm on the Saffir-Simpson wind scale, Michael is the strongest hurricane ever recorded making landfall on Florida’s Panhandle. It is also the strongest October hurricane ever known to come ashore in the continental United States, according to the historian Philip Klotzbach.

And by one important measure, Michael is the third strongest storm ever to come ashore in the continental United States. Only the Labor Day Storm, in 1935, and Hurricane Camille, in 1969, had a lower barometric pressure than this storm.

This intensity could spell potential disaster for Florida’s Panhandle. On Wednesday morning, Air Force Hurricane Hunters measured sustained, minute-long winds of 150 miles per hour near Michael’s eye. Winds that strong are capable of snapping trees in half, sending telephone poles flying through the air, and tearing the roof off of well-built homes. Such powerful gales often leave the area “uninhabitable for weeks or months,” according to the National Hurricane Center.

Michael’s winds are also unusually dangerous because they extend far out from the eye of the storm. The National Weather Service warns that more than 160,000 Floridians could experience sustained wind gusts in excess of 130 miles per hour on Wednesday. The storm will then bring hurricane-force winds to southwestern Georgia and southeastern Alabama.

But winds will not be Michael’s most life-threatening quality. More than 150 miles of Florida’s coastline will be temporarily swallowed by the ocean, as storm surge between nine and 14 feet swamps the shore. Nine feet of storm surge—in other words, the minimum forecast for this storm—is enough to turn cars into floating battering rams and cover one-story buildings.

What sticks out about Hurricane Michael’s development is that it got very strong very quickly. If you don’t live in Florida, and you feel like you only started hearing about Michael right before it made landfall, that’s because … you did. Unlike Hurricane Florence, which idled across the Atlantic Ocean as a powerful storm for days, Michael spun through the stages of hurricane formation relatively quickly. It became a tropical storm on Sunday afternoon. Only on Tuesday did it intensify into a major hurricane, with winds above 111 miles per hour.

President Donald Trump was correct when, speaking from the Oval Office on Wednesday, he said the storm “grew into a monster.” Meteorologists have their own name for this worrying phenomenon: “rapid intensification.”

How did Michael grow so strong, so fast? It got lucky. To borrow the president’s analogy, you can think of a hurricane as an enormous monster that feeds off oceanic energy (that is, warm ocean water) and converts it into atmospheric energy (that is, howling winds and terrible storm surge). This beast can grow to be very powerful, but it’s also scared by the slightest disturbance: Smaller local storms, or blustery winds in the high atmosphere, can weaken a hurricane or limit its growth.

Essentially, everything went right for the monster that became Hurricane Michael. As it neared the Florida Panhandle, it found waters that were very warm: almost 4 degrees Fahrenheit above normal. At the same time, it entered a patch of air that was relatively calm and windless. With lots of watery energy to devour, and few breezes to disturb its feast, Michael could quickly swell into a colossus.

Meteorologists have lately seen a number of storms that acted like this. Last year, Hurricane Harvey rapidly intensified in the hours before it made landfallnear Houston. As the climate warms, more hurricanes are projected to undergo a similar process. Kerry Emanuel, a professor of meteorology at MIT, has worried that climate-addled rapid intensification will make hurricanes increasingly difficult to predict. This would present a major problem, as the National Hurricane Center has struggled to improve its forecasts of hurricane intensity over the past three decades. While the government’s forecasts of hurricane storm track—that is, where a storm is going—have significantly improved since 1990, its forecasts of hurricane strength have not improved much at all in that time.

Even this week, the National Hurricane Center did not predict that Michael would make landfall as a major hurricane until late on Monday morning, roughly 48 hours before the storm came ashore. Its track forecast came much earlier: It predicted that some kind of tropical storm would make landfall in the Panhandle on Saturday afternoon.

Scientists won’t formally know whether climate change played a role in Michael’s rapid intensification for several months. But local weather experts have already said Michael is exactly what they would expect to see in a climate-changed world. John Morales, the chief meteorologist for Miami’s NBC station, joked on Twitter that Florida was now “#RecordsRUs” because of climate change.

Global warming’s effect on hurricanes is “like changing the speed limit on a highway,” he said. “The highest possible wind-speed that can be attained in a tropical cyclone is increasing thanks to a change in the thermodynamics.”

Yet rapid intensification may not even be the most important way that Hurricane Michael presages our coming, climate-changed future. To understand the coming future, look to the storm’s social landscape: The storm has made landfall in one of Florida’s poorest regions. In fact, every Florida county currently in a state of emergency has a higher poverty rate than Florida overall. Many residents of those counties live in mobile homes, which are not built to sustain hurricane-force winds.

It is, of course, a matter of chance where a hurricane strikes, and Hurricane Michael did not seek out the state’s most underserved area. But that is the point. It is always difficult—and expensive—for even well-off families to recover from a destructive storm. Yet most families are not prepared for them: More than 60 percent of Americans don’t have enough savings to react to a $1,000 emergency. Without both federal generosity and an unusually successful recovery, some of Hurricane Michael’s survivors will spend years recovering financially from an underserved, random act of weather.

In the world of the 21st century, many different random acts of weather will become more frequent and more destructive. When looking at the aftermath of Hurricane Michael, we should see not only a stand-alone disaster, but the shape of the coming storm.

Robinson Meyer writes for The Atlantic, where this article was originally published.

NEXT STORY: Rent Control Gearing Up to Be One of California’s Biggest Ballot Measure Fights on Election Day