Volunteer disaster response websites grow up

Code for America's disaster response websites get spun up faster with each storm season.

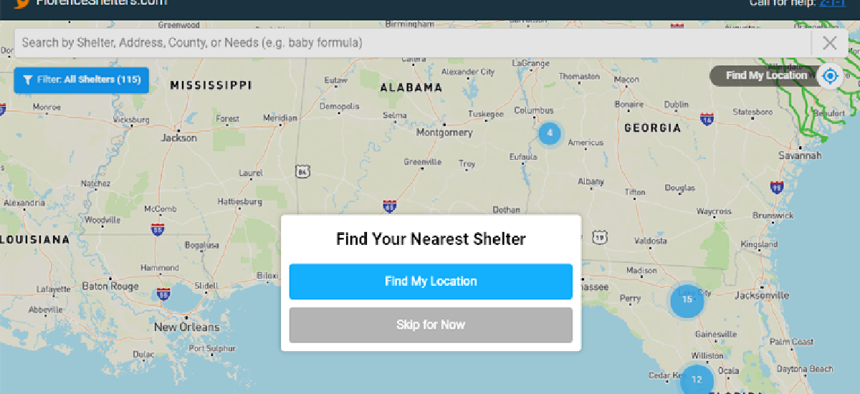

To help with preparation, response and outreach as hurricanes Florence and Michael barreled toward North Carolina and Florida earlier this year, Code for America (CfA) brigades in those areas spun up websites within 24 hours that included interactive maps of shelter locations and links to resources. The code was also posted on GitHub.

One reason for CfA's quick response was experience. After Hurricane Harvey caused extensive flooding in Houston in August 2017, people needed help finding shelter. Harveyneeds.org “sprang up out of necessity to share where shelters were and what was available immediately and what people might need,” said Michael Bishop, part of Code for Tampa Bay, Fla.

The brigades sprang into action again as Hurricane Irma made landfall the next month in Florida, and this year brigade members were able to use the Harveyneeds.org website as a template of sorts to stand up Florenceresponse.org in less than 24 hours. Michaelresponse.org went up even faster because teams were still in place from Florence.

“Since Michael happened so quickly after Florence, there wasn’t really a ramp-down period, so everyone was there, all the resources were in place,” said Christopher Whitaker, brigade program manager at CfA. “It was just basically moving things over and starting another instance.”

Another reason the sites spun up so quickly and stayed updated even during the storms is that brigades outside the affected areas stepped in to help. “There were people in Cleveland and New Jersey that were calling shelters at the height of the storm updating information,” said Chris Mathews of the Open Raleigh Brigade in North Carolina. “There were probably 40 to 50 people at the peak of the storm in Florence doing things.”

The backend of the websites features an application programming interface built with a Ruby on Rails application deployed on the Heroku cloud platform. The front end is a GitHub-hosted Jekyll site with a Javascript driving the map.

CfA members work with state, local and federal partners to get the data and information they need for the sites. For instance, Mathews said that Raleigh offered the site as another resource for residents through its social media posts on Twitter and Facebook. “I work in county government, so when we have [a government partner], we actually begin publishing the information through the normal information cycle our emergency operations centers use,” he added.

At the federal level, CfA participated in the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s crowdsourcing coordination calls, which the agency first orchestrated with digital volunteer networks during the 2017 hurricane season. That helped the brigade learn what others, such as the Crowd Emergency Disaster Response Digital Corps, which also grew out of Harvey response efforts, were doing.

“Particularly for Florence, we depended on CEDR Digital Corps to get some of our early information,” Whitaker said. “For Michael, [we worked] with the Red Cross in order to make sure we had the correct data.”

Florenceresponse.org differs from Harveyneeds.org in that “we limited the amount of information we were sharing on preparing for storms,” Bishop said. “There were great state and federal resources for those, so we didn’t really focus on anything that was necessary for that. We focused strictly on the shelter availability.”

The newer site has a textbot that provides the locations of the nearest shelters after users text a ZIP code to a specific number. In general, the codebase grows with each iteration, and the API now lets users download data as a CSV file.

Each new site has also grown the effort’s legitimacy, Bishop said. For instance, officials at North Carolina’s emergency operations center have told him they want the brigade to be a partner the next time a storm threatens the state.

“At the beginning of the Florence response, the county was a little skeptical: Everyone wants to help," but officials wonder if "the partners really going to be there long-term,” Bishop said. “By the end of the storm, by the second or third day, there was actually a change in the attitude in certain people at the county level and at the state level that Code for America’s response was being much more of a legitimate partner as opposed to a hindrance.”

At CfA’s 2018 Brigade Congress in Charlotte, N.C., Whitaker led a discussion on the future of these types of websites. The consensus is that they will continue and could be applied in other emergency situations, too. For instance, the brigade in Anchorage, Alaska, has already reached out to Bishop about adapting the site for its earthquake planning.

“Being networked together provides us both flexibility and capacity to respond not only to situations like natural disasters but other problems as well,” Whitaker said. “One of the advantages of being in a network as large ours -- right now we’re in 77 cities -- is that we through the network have a platform to share not only our code base, but lessons learned, our skills across the country.”

CfA has already started mapping out a 3.0 milestone of the API backend that will allow for additional features and make it more of a permanent solution, as opposed to spinning it up for each new storm.

Out of the four disaster response websites, only the one for Irma has been deactivated. The others will shutter once Houston, the Carolinas and Florida have ramped down their shelters and FEMA distribution centers, Whitaker said.