The Charter-School Teachers’ Strike in Chicago Was ‘Inevitable’

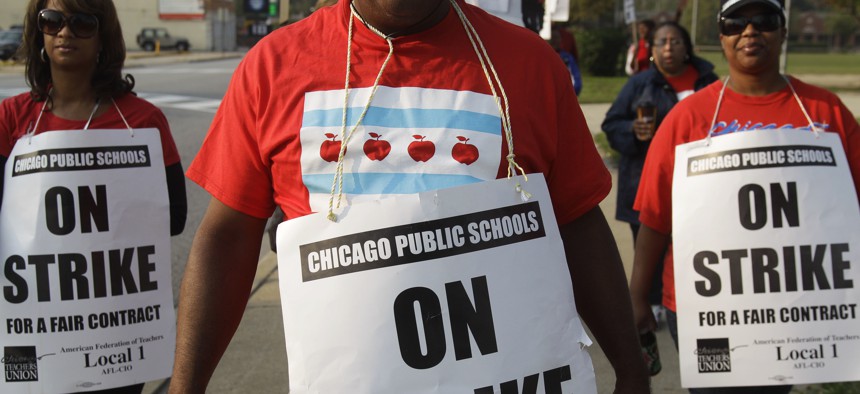

In this Sept. 17, 2016, file photo, teachers picket outside Morgan Park High School in Chicago. AP Photo

Connecting state and local government leaders

The move could signal a shift in the long, contentious relationship between teachers’ unions and these privately run schools.

Teachers’ strikes have been a constant across the country in 2018, popping up in six states, from West Virginia to Oklahoma. But so far, the wave of activism has been limited to educators at traditional public schools. That is, until earlier this week, when unionized teachers from one of Chicago’s largest charter-school networks, Acero Schools, took to the picket line. The strike is the first of its kind in U.S. history; although other charter-school teachers have unionized—collective bargaining is a requirement for charters in Hawaii and Maryland—these teachers are the first in the country to actually stage a walkout.

Teachers from all 15 Acero schools—which range from elementary to high school—resorted to a strike after failing to arrive at an agreement with Acero on Monday night over the terms of a new contract, in which they had requested higher salaries and smaller class sizes.

While teachers’ unions such as the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) had been gearing up for a possible strike for weeks, this decision to walk out is unprecedented: For decades, charter schools have championed themselves as a radical experiment in education that eschews the constraints of unions and traditional-public-school bureaucracy in favor of the flexibility to innovate. Now, at least in Chicago, the mentality seems to be shifting—and charter-school advocates fear it’s a sign that teachers’ unions, in a desperate effort to retain their clout, are co-opting charters for their own political reasons. Concurrently, the head of Chicago Public Schools, Janice Jackson, recommended on Monday that the city stop accepting proposals for new charter schools, a moratorium also supported by J. B. Pritzker, the governor-elect of Illinois.

“Ten years ago, that would have been a pretty unimaginable stance to be taken in this city,” says Elizabeth Todd-Breland, a historian at the University of Illinois at Chicago who studies education reform in the city. However, as a close watcher of Chicago charter schools, she long considered a strike like this to be “inevitable.” For several years, charter-school teachers have been joining the Chicago Alliance of Charter Teachers and Staff union, which recently merged with the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU)—an organization that is affiliated with the AFT and has historically opposed including charter-school teachers, Todd-Breland says. “I think after a number of conversations [among charter-school and traditional-public-school teachers’ unions], they came to the conclusion that they had common concerns as teachers,” she says, “and they had common concerns for students that made it make sense for them to come together.”

It’s impossible to separate all of this from the broader landscape of public education in Chicago. According to a recent analysis by the public-radio station WBEZ, around 200 public schools have been “radically shaken up” or closed altogether since 2002. The majority of the 70,000 affected students are black, while a substantial number are Latino. The majority-Latino population of Acero’s schools, then, is noteworthy—these students and families are, as WBEZ has put it, part of “the school-closing generation.” And teachers now on strike have highlighted the specific vulnerabilities of these students, with union negotiators citing the need for Acero to take the official position that the schools are “sanctuary schools,” for example.

Animosity has long existed between charter schools and teachers’ unions—even though the man who conceived of the idea of charter schools in the late 1980s was Al Shanker, AFT’s then-president. Such schools were envisioned, says Randi Weingarten, AFT’s current president, as “being an incubator of ideas” while still being “accountable, transparent, and [committed to] the mission of equity.” But it wasn’t long before Shanker and other labor leaders abandoned the idea, spurning the model as too beholden to the privately managed companies seeking to run the schools.

That antagonism has only intensified in the months since President Donald Trump tapped Betsy DeVos—a billionaire who has long advocated for charter schools—to be the country’s education secretary. The partisan divide in public opinion on charters and so-called school choice has subsequently widened. According to a 2018 poll conducted by Education Next, 44 percent of Americans support charter schools, a 5 percent increase from the previous year that was driven mostly by a boost in support among Republicans.

This heightened partisan tug-of-war over charter schools can in part be attributed to the idea that their role as so-called innovation laboratories is predicated on them being free from the constraints imposed by collective bargaining. And that’s a major reason this strike is historic: It’s the most conspicuous sign to date that teachers’ unions are succeeding at recruiting charter educators to the world of collective bargaining. “This certainly debunks a lot of myths,” Weingarten says. “Charter-school teachers are starting to recognize more and more that they need the union as a vehicle to create the power to have, at the very least, conversations” about pay and conditions

But Andrew Broy, the president of the Illinois Network of Charter Schools, argues that the strike is less of a myth buster and more of an underhanded ploy by the CTU to advance its own political interests at a time when teachers’ unions are scrambling to reorient their lobbying tactics and public relations.

“This was a long time coming,” Broy says, describing CTU’s efforts to recruit charter-school teachers as an “aggressive movement” that traces back six or so years. This endeavor, he argues, was a “political calculation” to limit the power of charters in the city, as the number of Chicago families sending their children to a neighborhood public school has declined in recent years, by subjecting charter schools to the same restrictive labor contract under which their public-school counterparts operate. In turn, this could undermine the competitive advantage of charter schools as unique educational entities with their own rules. “You can’t have that robust array of options if you just have a single contract,” Broy says.

But there’s another reason CTU likely ticked its organizing up a notch earlier this year, and it has to do with the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Janus v. American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees Council 31, which declared that the First Amendment prohibits labor unions from collecting membership dues from nonmembers. The ruling has, and will continue to have, major implications for teachers’ unions, says Martin West, a Harvard professor of education who studies charter schools and teachers’ unions. Hamstrung by their inability to rely on dues from nonmembers, West says, unions are “doing everything they can to organize as many members as possible”—fervently touting the benefits of union representation, for example, and marketing collective bargaining’s goals as focused on broader educational goals. So while the relationship may be strange, that traditional teachers’ unions and charter-school educators are becoming bedfellows is “hardly surprising,” West says.

It’s tempting to lump the charter-school strike in Chicago together with the recent spate of teacher walkouts across the country. And while there certainly are parallels, West cites the target of the charter-school teachers’ strike—Acero, a private organization—as the key distinction. The teachers who had been on strike earlier this year directed their demands at the government because the onus was on state politicians to pass legislation aimed at increasing school funding and improving their work conditions. Citing his own recent polling data, West says the notable increases in support for teacher pay and strikes are evidence that the teachers won in the court of public opinion; other surveys demonstrate similar shifts. But organizations like Acero are funded by the government, which in a sense means that they, too, “are the victim of a funding system,” West says. By striking against Acero, charter-school teachers are focusing on how the organization distributes the governmental funding it receives.

For Weingarten, such differences are secondary to the shared aspirations of teachers, whatever their school type. “As charters go from infancy to adolescence, those who want to succeed for the long haul have to have a stable, vibrant teaching force,” she says. “And that stable, vibrant teaching force wants a voice and agency.”

Regardless, experts predict that the Chicago development is a harbinger for more collective-bargaining alliances between charter-school and traditional-public-school teachers across the country. And similarly highlighting the distinction between the Acero strike and the statewide walkouts elsewhere in the country that kicked off in the spring, Broy points to politics. The strikes earlier this year took place in red-leaning states, most of which have long been skeptical of unions. It’s a different story in places like Chicago, where there’s broad public support for such organizing. And it’s in similarly big, left-leaning cities where Broy expects future developments like this one to surface.

Alia Wong is a staff writer and Natalie Escobar is an editorial fellow at The Atlantic, which originally published this article.

NEXT STORY: ‘Crowdsourcing for Health Care’ Raises Spirits—and Concerns