How States are Trying to Reduce Suicide Deaths

Kellie Johnston, 11, lost her father to suicide three years ago. Now, she’s telling her story to thousands of people to raise awareness and understanding of suicide. The Pew Charitable Trusts

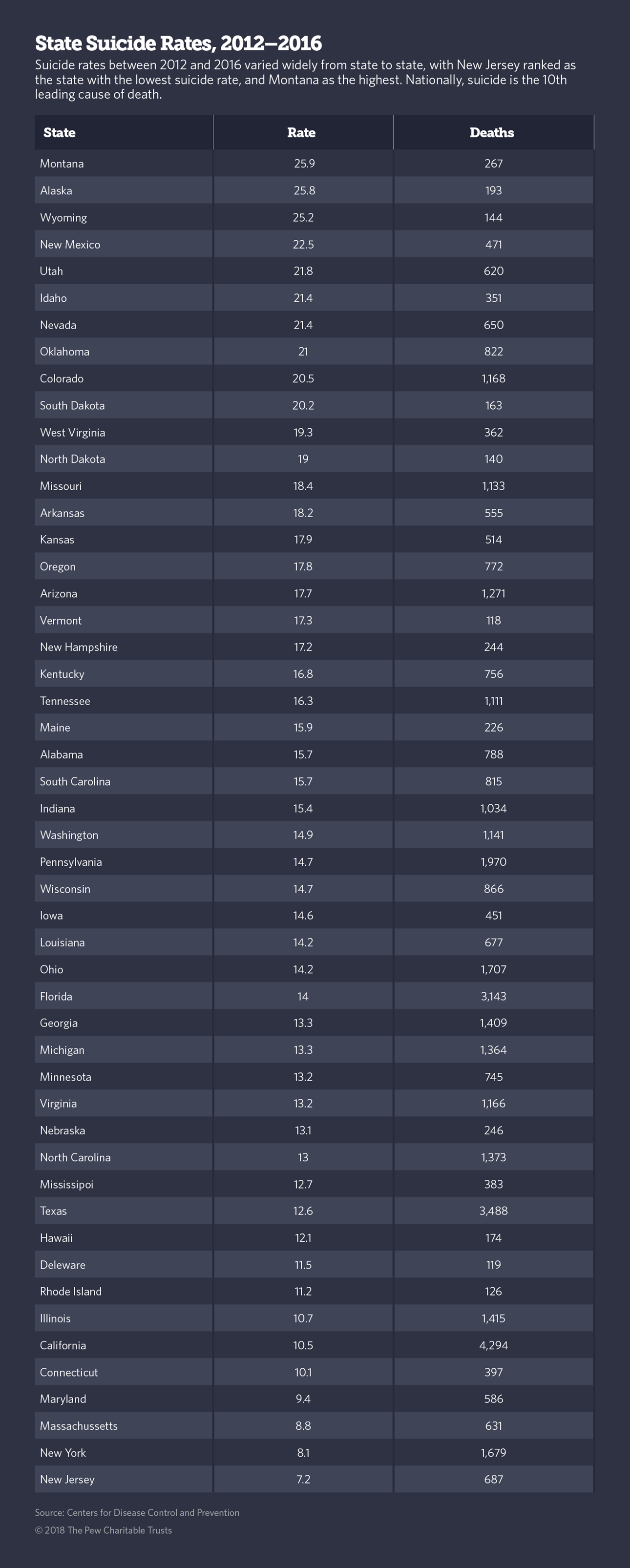

Nationwide, more than 47,000 Americans died by suicide last year, an increase of almost 5 percent over 2016.

Editors’ note: If you or a loved one is in distress, you can call 1-800-273-8255 (1-800-273-TALK). This story was originally published by Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts.

PORTLAND — For Portland resident Stephen Canova, thoughts of suicide came unexpectedly one December night. Then 20, a sophomore in college, unhappy and disconnected from his tightknit home community, he tried to kill himself.

“I had no idea I had it in me,” Canova said. “I don’t remember a lot about that night. But I do know this — when I tried to kill myself, I didn’t want to die. I just wanted the pain to go away. I wanted out.”

Nationwide, more than 47,000 Americans died by suicide last year, according to data released this week by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s a nearly 5 percent increase over 2016, when close to 45,000 people died. And it’s a continuation of a nearly 20-year rise in suicide rates that, along with drug overdose deaths, has been a leading factor in an ongoing decline in the average American life expectancy.

The 10th-leading cause of death among people of all ages, suicide is the second-leading cause of death among people 10 to 24, CDC numbers show.

Although youths aged 10 to 24 kill themselves at a lower rate than older people, youth suicides are climbing faster than suicides in other age groups. And the CDC says many suicide deaths could be avoided if more people knew how to recognize the signs of an imminent suicide attempt and the best ways to intervene.

In Canova’s case, 17 years ago, he said he had been separated from his family and community for the first time, and “just fell through the cracks.” After he attempted to kill himself, his roommate alerted his sister, who drove for an hour and showed up in time to get Canova to an emergency room and save his life.

Only 1 in 25 suicide attempts results in death. Research shows that most are preceded by warning signs such as extreme agitation or calm, withdrawal, and excessive drinking or drug use. Many people will talk about wanting to end their lives, say goodbye to others and give away belongings.

But if no one notices these signals or knows what to do about them, the results can be deadly.

That’s why Oregon and a handful of other states have started initiatives aimed at training medical professionals on suicide prevention so that family doctors, emergency room practitioners and other medical professionals who care for young people can be on the lookout for those at risk of suicide and intervene.

In addition, states are requiring teachers and other school personnel to learn suicide prevention skills, as well as teach students ways of coping with stress and detecting signs of suicide risk in themselves and others.

Many states also have laws outlining what to do if a suicide is attempted on school grounds, with some states requiring schools to develop a plan for dealing with the aftermath of suicides by students, teachers and other school personnel.

This year, at least 10 states—California, Colorado, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Kentucky, Maine, Rhode Island, Utah and Washington state—strengthened existing school-based suicide prevention laws, in most cases providing additional funding for mental health resources.

Next year, Oregon lawmakers are expected to consider a comprehensive new schools-based suicide prevention measure, as well as increased funding for mental health services in schools.

“We’ve seen incredible momentum in states to legislate on this issue,” said Nicole Gibson, state policy director for the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, a national suicide advocacy group with chapters in Oregon and other states.

“I think if we can promote suicide prevention in schools,” she said, “it will go a long way to support students who are at risk by making sure they get connected to mental health support and by creating a culture in schools that it’s a sign of strength to seek help.”

Follow-Up Care

Canova, now 36, is helping other youths who survive the crisis of a suicide attempt to make sure they get the treatment they need to avoid trying it again.

As follow-up services coordinator at Portland-based nonprofit Lines for Life, which works to prevent suicide and substance abuse, Canova says his own near-death experience helps him relate to people recovering from a suicide crisis. He and his team work with a group of local hospitals to ensure that patients who are discharged after a suicide attempt receive the care they need.

Suicide can affect anyone at any time of life, but research shows that people who survive a suicide attempt are at substantially higher risk of completing a subsequent suicide than those who have never tried it.

And in the weeks and months following release from a hospital after a suicide attempt or a visit to a doctor seeking help with thoughts of suicide, individuals are at high risk of killing themselves, said Jerry Rosenbaum, psychiatrist-in-chief at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Starting this month, Oregon will require all hospitals to provide follow-up services and referrals to mental health care for patients who are released after a suicide crisis.

Canova was lucky. When he was released from the hospital back in 2001, his sister and mother took him home and he received intensive therapy for six weeks before returning to college. He said he’s still using the coping skills he learned in those counseling sessions and hasn’t had suicidal thoughts since.

“I say to my friends, ‘I’m never going to do that again.’ But we all hit incredibly vulnerable moments in our lives when we feel like we’re a burden and our pain is too much,” he said. “Who’s to say that won’t happen again to me.”

Coping With Stress

Oregon’s suicide rate is higher than the national average, and the numbers are climbing. Last year, the number of suicide deaths in Oregon jumped 7 percent, compared to a 5 percent increase nationally.

“Every day, two people die by suicide in Oregon, and nobody knows about it,” said Dwight Holton, CEO of Lines for Life. “We don’t talk about it.”

“The stress teens feel about their grades and relationships is physiologically the same as the stress we adults feel about our jobs, our mortgages and our marriages, except that teens don’t have the coping skills most of us have developed over the decades,” Holton said.

Most young people know something about suicide, either from news reports of celebrity deaths or through social media and the experiences of friends and family. A recent young adult novel and Netflix series — “13 Reasons Why” — that features teen suicide has made the topic even more popular on social media and has been criticized for glamorizing suicide.

It’s highly unlikely that any youth today hasn’t heard something about suicide, Holton said. Still, many parents, teachers and other adults are wary of broaching the subject because of a misplaced fear that they might plant the idea of suicide and cause a young person to act on it, he said.

As a result, most youths have a limited understanding of how to detect warning signs, how to cope with their own suicidal thoughts or how to intervene if a friend or family member is showing signs of suicide risk.

And since teens are often reluctant to talk to their parents or teachers about their relationship problems and suicidal thoughts, the result can be deadly.

To make it easier for teens to talk about suicide, Lines for Life started a youth hotline that recruits high-school volunteers, puts them through more than 50 hours of training, and supervises them as they respond to mostly texts, chats and some phone calls from peers who may be grappling with depression and suicidal thoughts.

Called YouthLine, it provides crisis support and mental health referrals and is answered by young volunteers daily from 4 to 10 p.m. Pacific Time at (877) 968-8491, or by texting “teen2teen” to 839863. The service fielded more than 12,000 calls last year.

Amy Sloan, a senior at Woodrow Wilson High School here in Portland, has been responding to calls and messages after school for four hours, four days a week plus six-and-a-half hours once a week for two years now. She said she appreciates knowing how to talk to people about depression and suicide and may decide to study some type of behavioral health in college.

“Some people reach out to us because they’ve been struggling with depression and relapsed. I hate that there’s so much guilt and shame attached to relapse,” Sloan said. “I tell them that progress isn’t always linear and they can get better.”

Research shows that at least half of all people who have thoughts of suicide, whether they act on them or not, get better and stop thinking about ending their lives within one to three years, according to Harvard University research scientist Matthew Nock.

Loss Survivors

With the prevalence of suicide increasing, the number of children and young people affected by the loss of a parent, friend or other family member is also growing. As many as 32 people are affected by every suicide, according to the CDC. At 47,000 suicides in 2017, that’s more than 1.5 million people.

Public health officials are working to support this vulnerable population by making counseling more available in schools and the community.

Kellie Johnston was 8 years old when her father died by suicide three years ago. Her parents were divorced at the time and her father was living nearby. After her mother and older brother found out what happened, she said they told her he died because “his brain was sick.”

Later, Kellie, who spoke with Stateline alongside her mother, recalled, “They told me it was depression. And they told me depression was when someone was really, really sad. It confused me because I knew that you couldn’t die because you’re sad.”

Kellie and the rest of her family went to therapy right after her father died, and at 11, Kellie is still seeing her therapist once a week. She lives with her mother and brother, and her grandparents live nearby, just over the Columbia River from Portland in Vancouver, Washington.

She says she figured out what happened to her father by looking up the word “suicide” in the dictionary. “I had heard the word before and one day after school, I found it in the dictionary,” she said. “The definition had related words. It said depression. And I remember thinking that’s what happened to my dad. I was more relieved than sad.

“I understand why my mom didn’t want to tell me what happened to my dad. I was too young,” she said. “It makes sense.”

But the year after her father died, Kellie decided she wanted to help other kids who may have lost a loved one to suicide and those who may be depressed and thinking about suicide themselves.

With the help of her counselor, she put together a brief presentation and asked her middle-school principal if she could tell her story to the school. The principal declined her request, but the Oregon chapter of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention invited her to speak at a major rally in Portland in 2017.

This year she presented to an even bigger crowd of more than 2,000 demonstrators in Salem, speaking on the importance of talking about suicide. And she’s spoken twice to social work students at Lewis & Clark College in Portland.

Now that Kellie knows more about suicide, she said, the signs were all there with her dad. “He changed. He didn’t want to take care of himself. He had a more mellow voice and he was calmer than usual in his last month.”

In her speeches, Kellie said, “the most important thing I tell people, especially people who struggle with depression and may feel they’ll be judged if they ask for help, is that ‘it’s OK to ask for help.’”

NEXT STORY: What’s Really Happening to Retail?