Can Congress Void a Tribal Treaty Without Telling Anyone?

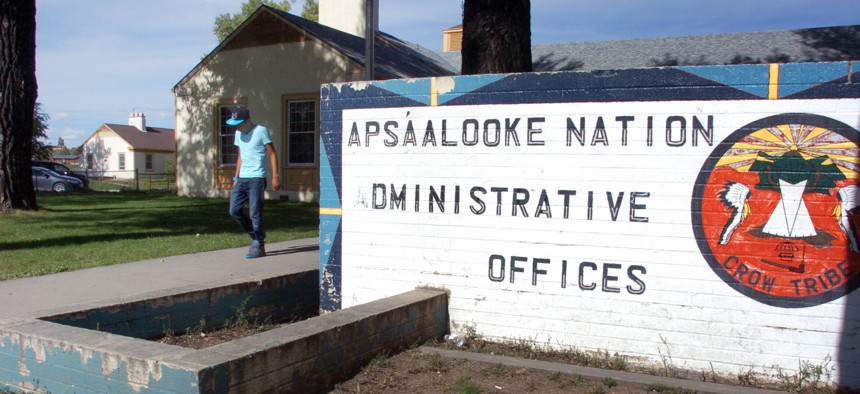

A boy is seen walking past the Crow Tribe's administrative offices in Crow Agency, Montana, Oct. 2, 2013. AP Photo

ANALYSIS | What’s at issue in Herrera v. Wyoming.

Herrera v. Wyoming, an Indian treaty-rights case argued in the Supreme Court last Tuesday, revolves around a basic of federal Indian law: No promise to Indian people actually binds the United States. Congress can unilaterally void any treaty or agreement. The only limit on this power so far has been a requirement that Congress say it is doing so. It is not supposed to act by “implication.” Whether that rules holds true will likely depend on the attitudes of the Court’s two newest justices.

The formal issue in Herrera is the conviction of a Crow tribal member for hunting elk out of season. The underlying issue is whether a treaty with the Crow tribe of Montana remains in force, or whether Congress junked it without telling anyone.

Clayvin Herrera was part of a group of Crow people who in January 2014 trailed a small herd of elk from the Crow reservation in southern Montana across the Wyoming state line into the federal Big Horn National Forest. They shot three elk and took the meat home for food. Wyoming officials, learning of the hunt, crossed into Montana and onto the Crow reservation to cite Herrera on misdemeanor charges of hunting out of season. (Even though Big Horn is federal land, the state has the power to regulate conservation matters there.)

Herrera and the tribe argue that the hunt was legal, because the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie guarantees the Crow “the right to hunt on the unoccupied lands of the United States so long as game may be found thereon, and as long as peace subsists among the whites and Indians on the borders of the hunting districts.” When Herrera was brought to trial, however, the state court refused to hear his argument. The treaty, the court said, was invalid under a 120-year-old Supreme Court case. He received a one-year suspended sentence, and three years’ suspension of all hunting privileges in Wyoming.

Who’s right about the treaty? Let’s take a quick look at the erratic history of federal Indian policy.

In the early Republic, the federal government made treaties of friendship with Indian tribes east of the Mississippi. In the 1830s, it stopped feeling friendly and removed the eastern Indians to the West. It set up reservations for eastern and western tribes and solemnly promised in treaties that the land would be theirs forever. In 1871, Congress decided there would be no more treaties, because Indian nations were no longer sovereigns; the courts soon confirmed that Congress could void any treaty without the consent of the tribes that had signed it. Next, from the 1880s until the 1930s, came the “allotment era.” The government decided to break up the reservations and “allot” much of the land to individuals, who could sell them. By the 1930s tribes had lost 60 percent of their previous land base. The New Deal was a brief respite: allotment ended and tribes were allowed to re-form their governments. Then in 1953 came the “termination era,” when Congress decided that the federal government would no longer provide services to tribes, or deal with their governments. It sold off some tribes’ reservation lands and proclaimed that those tribes no longer existed.

Not until the Nixon administration did Congress and the executive branch decide to deal again with tribes as genuine governments. (The famed Native writer Vine Deloria Jr. in 1971 hailed Nixon’s as “the best administration in American history” for its responsiveness to tribal concerns.) Since then, tribal governments have gained in strength and organization. In 1978, the high court made explicit the rule that tribal rights can’t disappear without “clear indications of legislative intent.”

State governments and tribes, however, have been ceaselessly at each other’s throats since the 19th century, fighting bitterly over issues of natural resources, fish, game, and wildlife management, taxation, and law enforcement.

Here’s how that history shook out in the case of the Crow. In 1890, Wyoming became a state. By 1896, in Ward v. Race Horse, the new state was asking the Supreme Court to void Indian treaty rights. Race Horse involved the elk-hunting rights of a member of the Bannock tribe of Idaho, under a treaty whose language was almost identical to that of the Crow. The high court held, 7-1, that the admission of Wyoming had silently voided all tribal hunting rights there. Because Wyoming had been admitted on an “equal footing” with other states, its powers over fish, game and wildlife couldn’t be limited by the Bannock treaty.

Race Horse, and its notion that statehood implies a silent repeal of treaties, staggered on until the Supreme Court decided Minnesota v. Mille Lacs Band of Chippewa Indians in 1999. The majority there held that the “equal footing” reasoning in Race Horse “rested on a false premise,” and “treaty rights are not impliedly terminated at statehood.”

So bye-bye Race Horse, hello easy case, right? Not so fast. In 1995, the Tenth Circuit had decided Crow Tribe v. Repsis. That case relied on Race Horse for the proposition that “[t]heTribe’s right to hunt reserved in the Treaty with the Crows, 1868, was repealed by the act admitting Wyoming into the Union.” Four years later, Mille Lacs trashed every element of Race Horse. But it didn’t say magic words like, “Pay attention now gang ‘cause see before your astonished eyes we are overturning Race Horse ta-da note overturningness of the overturn.”

And so the state argues that Race Horse remains a valid precedent. Whatever the law may be in Minnesota, it claims, in Wyoming tribes don’t have hunting rights. Second, the state points to Repsis, in which the Crow lost on the treaty-rights isue; Mille Lacs or no Mille Lacs, the state argues that no member of the tribe can ever re-litigate the issue, under a doctrine called “issue preclusion.” The tribe, however, argues that since Mille Lac, Race Horse sleeps with the cutthroat trout (Wyoming’s state fish). And because Repsis is based on a repudiated precedent, it does not “preclude” Herrera from arguing for treaty rights.

The argument Tuesday did not draw a lot of attention in Washington; but it was one of the most dramatic I can recall, sparked by a remarkable performance from Justice Neil Gorsuch.

The Gorsuch nomination in 2017 was opposed by most civil-rights groups; but it was hailed by tribal advocates. A native of Colorado, Gorsuch heard a number of Indian cases as a judge of the Tenth Circuit. From his opinions, wrote John Dossett, then general counsel of the National Congress of American Indians, Gorsuch “appears to be both attentive to the details and respectful to the fundamental principles of tribal sovereignty and the federal trust responsibility.”

The argument Tuesday left little doubt that Gorsuch was staking out Indian law as his turf. When George Hicks, representing Herrera, rose to argue, Justice Samuel Alito was waiting for him. Alito is no fan of any minority rights, and was particularly brusque about tribes in a 2013 case, Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl. On Tuesday, he seemed to want to prevent Hicks from even reaching the treaty issue. He went into bully mode, asking nearly a dozen niggling technical questions on the preclusion issue.

Gorsuch seemed to lose his patience, noting that the state hadn’t brought up that issue in lower courts. Then he added, “If [it] wasn’t raised by the district, passed on by the district court, relied on by the district court, in this proceeding, why should we enmesh ourselves in the excellent Wyoming law of issue preclusion?” He gave Hicks permission to move ahead to the actual issue. Alito did not open his mouth again until Hicks’s argument was done.

In contrast to Gorsuch, Justice Brett Kavanaugh was opposed by Indian advocacy groups—in part because of his legal work opposing a federal program for Native Hawaiians. And on Tuesday, he seemed convinced that Race Horse, the 1895 treaty-voiding decision, was still good law, even though Mille Lacs a century later had rejected all its reasoning. The Court had the chance “to say the Race Horse decision is gone. And that’s not what we said,” he noted. “[M]aybe we should have said it’s gone, but we didn’t.”

Justice Stephen Breyer then gave a brief lesson—suitable for any first-year Constitutional Law class—on the workings of a nine-member court. In Mille Lacs, Breyer said, the court trashed all three parts of the Race Horse decision.

[P]ossibly [the Court] should have added a fourth thing, and, therefore, the words ‘Race Horse is overruled,’ but the Court didn’t. I can understand that. I can perhaps understand that better than [counsel for Wyoming]. There are a lot of things to do every day, and you have to write your opinions and you start putting in a word like ‘overruled’ and some of your colleagues might think: ‘Don’t do it, you don’t know what you’re getting, et cetera. All we have to decide for [Mille Lacs] is that Race Horse doesn’t bind us, okay?’

Despite its low media profile, Herrera has been very closely watched in Indian country. The stakes are high for federal land management, for states, for tribes, and for hunters, Indian and non-Indian alike.

Herrera argues that for him and his family, the case is a matter of life and death. “[W]hether Petitioner’s family has food on the table during unforgiving Montana winters,” his lawyers wrote in their petition for certiorari, “depends on his ability to exercise the off-reservation hunting rights long ago granted to his tribe.”

Garrett Epps is a Contributing Editor for The Atlantic, which originally published this article.

NEXT STORY: Paying the Homeless to Clean Up City Parks