Active-Shooter Drills Are Tragically Misguided

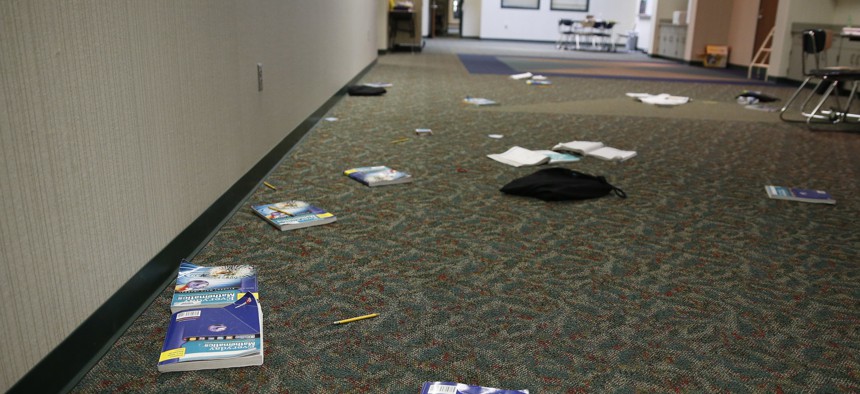

In this May 6, 2016, photo, books and supplies litter the floor as a class evacuated the area during an intruder drill at Forest Dale Elementary School in Carmel, Ind. AP Photo

Connecting state and local government leaders

There’s scant evidence that they’re effective. They can, however, be psychologically damaging—and they reflect a dismaying view of childhood.

At 10:21 a.m. on December 6, Lake Brantley High School, in Florida, initiated a “code red” lockdown. “This is not a drill,” a voice announced over the PA system. At the same moment, teachers received a text message warning of an active shooter on campus. Fearful students took shelter in classrooms. Many sobbed hysterically, others vomited or fainted, and some sent farewell notes to parents. A later announcement prompted a stampede in the cafeteria, as students fled the building and jumped over fences to escape. Parents flooded 911 with frantic calls.

Later it was revealed, to the fury of parents, teachers, and students, that in fact this was a drill, the most realistic in a series of drills that the students of Lake Brantley, like students across the country, have lately endured. In the year since the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School last February, efforts to prepare the nation’s students for gunfire have intensified. Educators and safety experts have urged students to deploy such unlikely self-defense tools as hockey pucks, rocks, flip-flops, and canned food. More commonly, preparations include lockdown drills in which students sit in darkened classrooms with the shades pulled. Sometimes a teacher or a police officer plays the role of a shooter, moving through the hallway and attempting to open doors as children practice staying silent and still.

These drills aren’t limited to the older grades. Around the country, young children are being taught to run in zigzag patterns so as to evade bullets. I’ve heard of kindergartens where words like barricade are added to the vocabulary list, as 5- and 6-year-olds are instructed to stack chairs and desks “like a fort” should they need to keep a gunman at bay. In one Massachusetts kindergarten classroom hangs a poster with lockdown instructions that can be sung to the tune of “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star”: Lockdown, Lockdown, Lock the door / Shut the lights off, Say no more. Beside the text are picture cues—a key locking a door; a person holding up a finger to hush the class; a switch being flipped to turn off the lights. The alarm and confusion of younger students is hardly assuaged by the implausible excuses some teachers offer—for instance, that they are practicing what to do if a wild bear enters the classroom, or that they are having an extra-quiet “quiet time.”

In the 2015–16 school year, 95 percent of public schools ran lockdown drills, according to a report by the National Center for Education Statistics. And that’s to say nothing of actual (rather than practice) lockdowns, which a school will implement in the event of a security concern—a threat that very well may turn out to be a hoax, perhaps, or the sound of gunfire in the neighborhood. A recent analysis by The Washington Post found that during the 2017–18 school year, more than 4.1 million students experienced at least one lockdown or lockdown drill, including some 220,000 students in kindergarten or preschool.

In one sense, the impulse driving these preparations is understandable. The prospect of mass murder in a classroom is intolerable, and good-faith proposals for preventing school shootings should be treated with respect. But the current mode of instead preparing kids for such events is likely to be psychologically damaging. See, for instance, the parting letter a 12-year-old boy wrote his parents during a lockdown at a school in Charlotte, North Carolina, following what turned out to be a bogus threat: “I am so sorry for anything I have done, the trouble I have caused,” he scribbled. “Right now I’m scared to death. I need a warm soft hug … I hope that you are going to be okay with me gone.”

As James Hamblin wrote for The Atlantic last February, there is precious little evidence that the current approach is effective:

Studies of whether active-shooter drills actually prevent harm are all but impossible. Case studies are difficult to parse. In Parkland, for example, the site of the recent shooting, Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, had an active-shooter drill just [a] month [before the massacre]. The shooter had been through such drills. Purposely countering them may have been a reason that, as he was beginning his rampage, the shooter pulled a fire alarm.

Moreover, the scale of preparedness efforts is out of proportion to the risk. Deaths from shootings on school grounds remain extremely rare compared with those resulting from accidental injury, which is the leading cause of death for children and teenagers. In 2016, there were 787 accidental deaths (a category that includes fatalities due to drowning, fires, falls, and car crashes) among American children ages 5 to 9—a small number, considering that there are more than 20 million children in this group. Cancer was the next-most-common cause of death, followed by congenital anomalies. Homicide of alltypes came in fourth. To give these numbers yet more context: The Washington Post has identified fewer than 150 people (children and adults) who have been shot to death in America’s schools since the 1999 shooting at Columbine High School, in Colorado. Not 150 people a year, but 150 in nearly two decades.

Preparing our children for profoundly unlikely events would be one thing if that preparation had no downside. But in this case, our efforts may exact a high price. Time and resources spent on drills and structural upgrades to school facilities could otherwise be devoted to, say, a better science program or hiring more experienced teachers. Much more worrying: School-preparedness culture itself may be instilling in millions of children a distorted and foreboding view of their future. It’s also encouraging adults to view children as associates in a shared mission to reduce gun violence, a problem whose real solutions, in fact, lie at some remove from the schoolyard.

We’ve been down this road before. In an escalating set of preparations for nuclear holocaust during the 1950s, the “duck and cover” campaign trained children nationwide to huddle under their desk in the case of a nuclear blast. Some students in New York City were even issued dog tags, to be worn every day, to help parents identify their bodies. Assessments of this period suggest that such measures contributed to pervasive fear among children, 60 percent of whom reported having nightmares about nuclear war.

Decades later, a new generation of disaster-preparedness policies—this time geared toward guns rather than nuclear weapons—appear to be stoking fear once again. A 2018 survey by the Pew Research Foundation determined that, despite the rarity of such events, 57 percent of American teenagers worry about a shooting at their school. This comes at a time when children are already suffering from sharply rising rates of anxiety, self-mutilation, and suicide. According to a landmark study funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, 32 percent of 13-to-18-year-olds have anxiety disorders, and 22 percent suffer from mental disorders that cause severe impairment or distress. Among those suffering from anxiety, the median age of onset is 6.

Active-shooter drills reflect a broad societal misunderstanding of childhood, one that features two competing images of the child: the defenseless innocent and the powerful mini-adult. On the one hand, we view children as incredibly vulnerable—to hurt feelings, to non-rubberized playground surfaces, to disappointing report cards. This view is pervasive, and its consequences are now well understood: It robs children of their agency and impedes their development, and too often prevents them from testing themselves either physically or socially, from taking moderate risks and learning from them, from developing resilience.

But on the other hand, we demand preternatural maturity from our children. We tell them that with hockey pucks and soup cans and deep reservoirs of courage, they are capable of defeating an evil that has resisted the more prosaic energies of law-enforcement officers, legislators, school superintendents, and mental-health professionals. We ask them to manage not the everyday risks that they are capable of managing—or should, for their own good, manage—but rather the problems they almost by definition cannot.

This second notion of the child stems from what I call adultification, or the tendency to imagine that children experience things the way adults do. Adultification comes in many forms, from the relatively benign (dressing kids like little adults, in high heels or ironic punk-rock T-shirts) to the damaging (the high-stakes testing culture creeping into kindergartens). We also find adultification in the expectation that kids conform to adult schedules—young children today are subjected to more daily transitions than were previous generations of children, thanks to the dictates of work and child-care hours and the shift from free play to more programmed activities at school and at home.

Similarly, we expect children to match adults’ capacity to hurry or to be still for long periods of time; when they fail, we are likely to punish or medicate them. Examples abound: an epidemic of preschool expulsions, the reduction in school recess, the extraordinary pathologizing of childhood’s natural rhythms. ADHD diagnoses, which have spiked in recent years, are much more common among children who narrowly make the age cutoff for their grade than among children born just a week or so later, who must start kindergarten the following year and thus end up being the oldest in their class; this raises the question of whether we are labeling as disordered children who are merely acting their age. The same question might be asked of newer diagnoses such as sluggish cognitive tempo and sensory processing disorder. These trends are all of a piece; we’re expecting schoolchildren to act like small adults.

Adultification is a result of a mind-set that ignores just how taxing childhood is. Being small and powerless is inherently stressful. This is true even when nothing especially bad is going on. Yet for many children, especially bad things are going on. Nearly half of American children have experienced at least one “adverse childhood experience,” a category that includes abuse or neglect; losing a parent to divorce or death; having a parent who is an alcoholic or a victim of domestic violence; or having an immediate family member who is mentally ill or incarcerated. About 10 percent of children have experienced three or more of these destabilizing situations. And persistent stress, as we are coming to understand, alters the architecture of the growing brain, putting children at increased risk for a host of medical and psychological conditions over their lifetime.

How misguided to take young brains already bathed in stress hormones and train them to fear low-probability events such as mass shootings—and how little most of us think about what we’re doing. Whereas much adultification involves subjecting kids to things we adults do to ourselves (sleep too little, rush too much), we are at some distance from the harms being inflicted in schools. Even though only a quarter of shootings that involve three or more victims take place at schools, we seldom hear about realistic live-shooter drills in nursing homes, places of worship, or most workplaces. They would likely inconvenience if not incense adults, and scare away business. But we readily force them on children.

If today’s students feel anxious, perhaps it’s partly because, after being told by adults that they’re not capable of handling life’s little challenges, those same adults are bequeathing them so many big challenges, ranging from the college-admissions rat race to an economically precarious future; from climate change to gun violence. Of course, this impulse fits into a longer history of dispatching children to fix adults’ messes, a history that connects the young civil-rights icons Ruby Bridges and Claudette Colvin with the Parkland survivors-turned-activists David Hogg and Emma González.

Audrey Larson, a Connecticut high-school student, would seem to fit squarely into this tradition, having recently won an engineering prize for designing a collapsible, bulletproof wall intended for use in classrooms. Because she grew up near Sandy Hook Elementary School, the site of a 2012 massacre, she wanted to do something tangible to alleviate her classmates’ fear of school shootings. Larson told a reporter that “we can’t wait around anymore” while politicians dither on gun violence. One judge lauded the project’s “robustness and detailed design work.” But I was struck more by the contrast between her prizewinning effort and her earlier, more whimsical entries: a dog-scratching gadget and a pair of glowing pajamas.

Our feverish pursuit of disaster preparedness lays bare a particularly sad irony of contemporary life. Among modernity’s gifts was supposed to be childhood—a new life stage in which young people had both time and space to grow up, without fear of dying or being sent down a coal mine. To a large extent, this has been achieved. American children are manifestly safer and healthier than in previous eras. The mortality rate of children under 5 in the United States today is less than 1 percent (or 6.6 deaths per 1,000 children), compared with more than 40 percent in 1800. The reduction is miraculous. But as in so many other realms, we seem determined to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory.

At just the moment when we should be able to count on childhood, we are in danger of abandoning it. When you see a toddler dragged along with her parents to a restaurant long past bedtime; or when you consider the online kindergarten-readiness programs that are sprouting up like weeds (preventing kids from rolling around in actual weeds); or when you think about that 12-year-old North Carolina boy writing an anguished farewell note to his parents, it’s hard to avoid the sense that we are preparing a generation for a kind of failure that may not be captured in actuarial statistics. Our children may be relatively safe, but childhood itself is imperiled.

Erika Christakis is the author of The Importance of Being Little: What Young Children Really Need From Grownups. This article was originally published in The Atlantic.

NEXT STORY: Salt Doesn’t Melt Ice—Here’s How It Actually Makes Winter Streets Safe