The Next Parkland Could Happen Anywhere

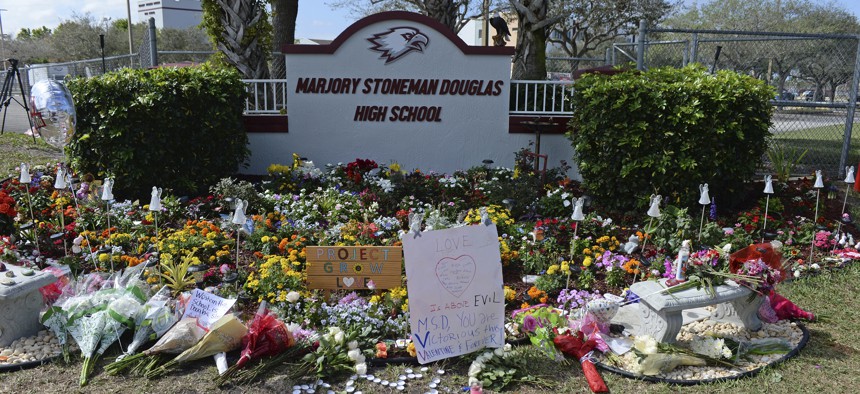

Students and parents visit a make shift memorial setup at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in honor of those killed during a mass shooting to mark the one year anniversary on Feb. 14, 2019. mpi04/MediaPunch /IPX via AP Photo

Connecting state and local government leaders

Schools are trying to bolster security, but they can only do so much to prevent another mass shooting.

In the wake of a tragedy, there’s a race to understand exactly why it happened and what could have been done to prevent it. Maybe local law enforcement could have done more; maybe armed teachers would have helped; maybe the federal government should have been investigating the shooter as a terrorist. The shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, last Valentine’s Day, in which 17 people were killed and more than a dozen others were injured, was no different.

The Marjory Stoneman Douglas Public Safety Commission, an investigative panel convened by the state of Florida, was tasked with laying out the facts of what happened in the 78 minutes between when a gunman was dropped off by an Uber near campus and when he was detained by police. In January, it released a 439-page report providing some answers about what went wrong, cataloging breaches of security, chaotic protocols, and a lack of communication systems for teachers to relay the seriousness of the situation across campus.

“School safety in Florida needs to be improved,” the report opens. “All stakeholders—school districts, law enforcement, mental health providers, city and county governments, funding entities, etc.—should embrace the opportunity to change and make Florida schools the safest in the nation.” But often, tragedies are tragedies for a reason; they’re not supposed to happen, but they do—even in the most secure environments.

The report is a searing indictment of the failures that day and those that led up to it, but it also offers several best practices for preventing the next school shooting. For many school-safety experts, the recommendations are all too familiar. “Overall, there were some solid recommendations in terms of best practices that came out of Parkland. That’s the good news,” Kenneth Trump, who runs National School Safety and Security Services, a school-safety consulting firm, told me. “The bad news is they’re the same as the best practices that came out of Sandy Hook, which were the same best practices that were learned after Columbine. So they’re not new.”

Trump, who is of no relation to the president, says that in the wake of high-profile shootings, school districts and legislators will often rush to implement fixes that aren’t ultimately maintained. Cameras are found to no longer be working once the incident has faded; security protocols are forgotten with turnover. School safety isn’t always just the security measures you can see, Trump says, but also the ecosystem on campus that creates an environment that shuns bullying, encourages students to report suspicious behavior, and fosters a healthy school climate.

That’s a difficult thing to explain to parents who fear losing their children in school shootings, which are still extraordinarily rare, Trump says. “You can’t just point to a culture of safety as easily as you can point to a camera and say, ‘Trust us, your child’s school is safer,’ ” he says.

The search for active prevention measures has led some people to believe that the federal government should play a larger role. The Department of Homeland Security and the FBI, among other agencies, are already trying to prevent domestic terrorism, the thinking goes. And many school shootings fit the mold, says Martha Crenshaw, a senior fellow at the Center for International Security and Cooperation at Stanford University, as a “type of violence that shocks or surprises, something that provokes outrage.” That outrage could stem from the nature of the crime or the nature of the victim, she says. “Who could be more innocent than schoolchildren?”

The National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, known as START, at the University of Maryland has been tracking terror incidents through the Global Terrorism Database. And there has been a disconnect between the government definition of terrorism, particularly domestic terrorism, and the working definition used by START, Gary LaFree, the group’s founding director, told me. To the organization, an incident of terrorism needs to be intentional; involve violence; be committed by someone other than a government agent; and, perhaps most importantly, have a political, economic, religious, or social goal. Under that definition, school shootings could be considered terrorism in some cases, as Columbine was and as the Parkland shooting likely will be, LaFree says.

The government has a definition of domestic terrorism in the federal code—acts of violence that are intended to influence government policy or “affect the conduct of the government by mass destruction, assassination, or kidnapping”—but there is no federal domestic-terrorism law to back it up, David Schanzer, the director of the Triangle Center on Terrorism and Homeland Security at Duke University, told me. That means the federal government can’t charge people with a violation of a terrorism law; instead, it could charge them with a hate crime, or violations of interstate-commerce laws, or a similar offense. (Murder is a state crime, not a federal one.) “You have to bring a charge that reflects the circumstance of what occurred,” Schanzer says.

But that’s all reactive, the what comes after the shooting. How could the government treating potential school shooters as terrorists help prevent them? That depends on whether potential shooters are flagged for monitoring by the FBI or any other agency, perhaps after a friend or family member reports a potential plot.

Trump noted that after the Columbine shooting, there was a focus at the federal and state level to take a comprehensive look at school safety—“from prevention to preparedness, from threat assessment to prevention, mental-health services for kids, school resource officers, emergency-planning drills and exercises.” These are things that have worked, he says, not only in warding off a school shooter, but in keeping a school safe on a day-to-day basis.

But identifying perpetrators ahead of time is a much harder challenge. Like terrorist incidents, school shootings are rare, tragic, and can only sometimes be explained. After every school shooting, Crenshaw says, “people wonder what happened—missed opportunities and interventions, lost chances” to find shooters before they wreaked havoc. Yet, Crenshaw adds, sometimes school shootings, like terrorist incidents, are virtually impossible to prevent. “If you went back and replayed, it might be just really hard to find that [intervention] point.”

Adam Harris is a Staff Writer at The Atlantic, which originally published this article.

NEXT STORY: How a Health Department Is Working to Contain a Measles Outbreak