Time to Try Something New: Parliamentary State Government

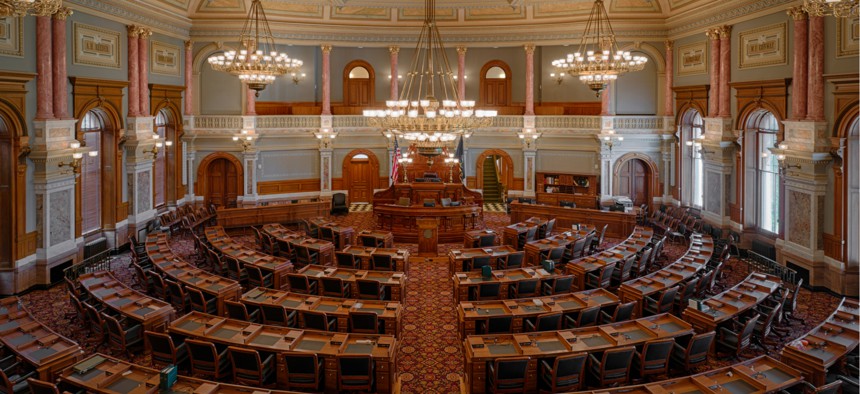

House of Representatives chamber of the Kansas State Capitol building Nagel Photography / Shutterstock.com

COMMENTARY | If states truly are "laboratories of democracy," it is time one traded its legislature and governor for a parliament and prime minister.

These are tumultuous times for Virginia politics. The three statewide elected officials—governor, lieutenant governor, and attorney general—are all embroiled in scandals. Many leaders, both inside the Commonwealth and outside, have said these men lack the moral authority to lead and have called for their resignations, although so far all have stayed put. But this dramatic standoff has also provoked some to suggest a more radical solution for Virginia—adopting a parliamentary system that would have swiftly and effectively dealt with this matter, avoiding embarrassment.

While considering a parliamentary system might be dismissed out of hand in the good ol’ U.S. of A., it really shouldn’t be.

Scandal isn’t the only reason to remove a politician from power. Parliaments routinely replace their leaders when those leaders fail to perform. Since prime ministers are just technically members of parliament chosen to lead the government, a new prime minister can be readily picked without major shuffling. In a presidential system—which is replicated in the states—significant harm is usually done before the rare occasion a chief executive is forced from office.

The Status Quo

For the most part, the fifty state government structures mimic each other and the federal government. Every state elects a governor to be the chief executive of its government. Legislatures are elected separately. While this is the norm in the United States, in other countries and their provinces, parliamentary systems dominate.

Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis famously wrote that the states are laboratories of democracy. If that’s true, how come there have been so few true divergences in governance?

The most notable exception is Nebraska’s unicameral legislature. And one could argue, Texas has the closest thing to a prime minister of a semi-presidential system—the lieutenant governor actually sets the agenda for the state senate. Nevertheless, strong executive systems dominate all fifty jurisdictions.

Looking Back

Where did this start? Looking again at Virginia, the House of Burgesses was created in 1619 and continued until the Revolutionary War. It was the first democratically-elected legislative body in the British American colonies. (To be fair, elections were held in town squares by voice votes of land-owning men who supported other land-owning men.) The legislature’s power was subordinate the royally appointed governor and the Governor’s Council, a body of appointed advisors. While the governing structures varied across the Thirteen Colonies, many common features prevailed. Following independence, as the colonies became states, they largely stuck to what they knew and kept the role of the governor.

Back in Britain, power continued to shift from the monarch to parliament over hundreds of years of reforms. Eventually, the prime minister of the House of Commons became the head of government and the monarch retained the ceremonial role of head of state. This parliamentary system spread throughout the world and is characteristic of former British dominions.

The vast majority of states were added to the union post-Revolution. And before achieving statehood, many U.S. states were territories or parts of territories first. These jurisdictions were administered by the federal government with governors who were appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate. When receiving admission to the Union, these new states, complying with the constitution’s request for republican form of government, followed tradition and modeled the presidential system.

There is nothing in the U.S. Constitution prohibiting a state from experimenting with a parliamentary government structure. States have had many opportunities to change. The antebellum period was an era of continuous constitutional revision. And again during the Progressive era, state constitution and amendment making reforms were rampant. Even today, we are experimenting with new forms of elections, like rank choice voting. However, separation of powers continued to play a major role in American constitutional thinking, preserving the presidential system.

Challenging the Narrative

Parliaments fundamentally rely on parties to function—there has to be a majority of like-minded representatives willing to pass laws and support the government. In America, we have always had an uneasy relationship with party politics. George Washington famously warned about the dangers of parties; the Constitution is silent on the topic. Scholars argue that, despite the early split into a two-party system, partisan politics remained taboo—and to this day the term maintains a negative connotation. We traditionally like to think of our executive leaders set aside strict party positions and put their judgement of what is best for the country first. Framers of state constitutions, therefore, opted to give significant power to an individual, rather than a party, to run the government.

Presidential systems create an antagonistic relationship between the executive and the legislative functions—the threat of gubernatorial veto is strong. It also contributes to slow and incoherent government. For example, ten states started fiscal year 2018 without a budget in place.

As such, parliaments do tend to spend more money than presidential systems, but they also make it easier to enact popular policies. They are believed to be less susceptible to autocracy as well.

Some might argue that a consolidated executive-legislature would eliminate an essential check on power where one party rules the entire state. However, trifectas—where one party holds the governorship, a majority in the state senate, and a majority in the state house—dominate state governments. According to Ballotpedia, there are currently 36 state government trifectas: 14 Democratic and 22 Republican. Party politics have already taken hold of state governments.

During the Progressive reform era, there was a move to the strong executive at both city and state government level. Local governments needed so much cleaning up, it was thought, that only a strong executive could enforce an apolitical administration. Apolitical, however, does not mean more democratic. Parliamentary systems install elected officials to head the important functions of government. These leaders are answerable to both the constituency that elected them and their peers in the legislature.

A representative bureaucracy is not entirely foreign. All states currently have a number of constitutional officers elected by the people. Forty-three states elect their Attorney General. Thirty-five elect a Secretary of State, whose role is usually to maintain records and monitor elections. Texas, for example, elects four agency heads in statewide elections, including the Commissioner of Agriculture. While these elections insert the will of the people, it’s a four-year performance review and not the daily one a parliamentary system would provide.

Legislative oversight of the executive is an essential role, but one that is abdicated for most of the year in many states. In four states, the legislature meets only every other year. This is certainly a check on legislative power, but it also limits the nimbleness of the government to respond to challenges and maintain accountability. Not to mention, if funds need to be appropriated or the law needs to be amended to deal with a new and pressing issue, the governor must call a special session or wait until the next scheduled session.

There are certainly pros and cons to each system. And an effort to switch to a more parliamentary system is up against a considerable amount of institutional history. But the fact that, over hundreds of years, none of the fifty states have experimented with a parliament is astounding. Maybe someone should open up the laboratories again.

Trevor Langan is a Capital City Fellow in the District of Columbia. He previously worked as a researcher at the National League of Cities.

NEXT STORY: Rescue Network Sends Southern Puppies North