Political Candidates Don’t Always Tell the Truth (And You Can’t Make Them)

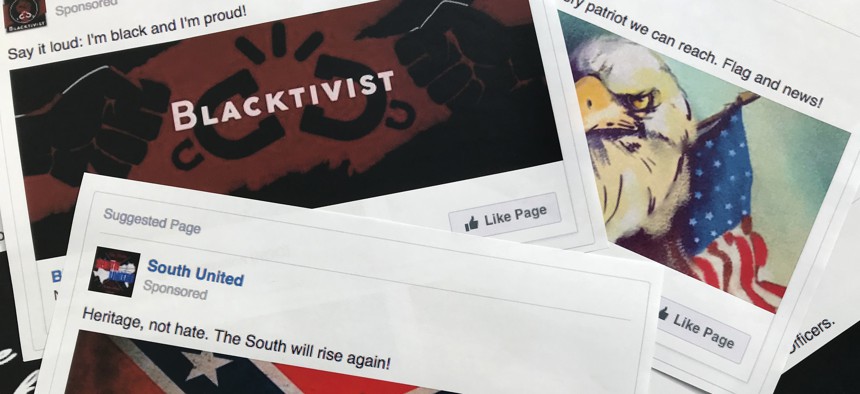

Facebook ads linked to a Russian effort to disrupt the 2016 presidential election. Some states are trying to regulate political ads by requiring more disclosure from social media companies. AP Photo/John Elswick

States have tried to prohibit candidates from telling lies in political advertisements. But the experience in Montana and other states shows that isn't so easy.

This story was originally published by Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts.

Say you’re a politician running for office, and you want to call out your opponent’s votes against education or guns. If you’re in Montana, a bipartisan group of lawmakers has a new demand: Prove it.

Legislators in Big Sky Country want candidates or political groups who attack a voting record to back up the charge with specifics. Under legislation that has been filed repeatedly in recent years, ads would have to include the title and number of a bill or resolution referred to and the year when the vote was taken.

But the bruising fight to impose a new law in Montana shows just how difficult it is for states to restrict political speech.

Since 2011, Montana courts have struck down three similar attempts to require truth in political advertising, saying the laws were “unconstitutionally vague” and therefore infringed on the free speech rights of Montanans.

“Unfortunately, the wording used was too broad and wasn’t enforceable,” said Democratic state Rep. Kimberly Dudik, who authored an unsuccessful fix this year. “This isn’t something that’s done a lot. We’re really breaking new ground here.”

To be sure, some two dozen states have for years made it illegal to lie in a political campaign about certain claims, such as when polls open or whether a candidate got an endorsement.

But now, in a country whose president has been shown to have uttered thousands of falsehoods in the past year, and as opinion surveys show an electorate continually skeptical of both public officials and the media, many experts say voters deserve to know they’re getting the truth from political advertising.

Those crackdowns don’t come easy, though. The U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment protects free speech in most forms, and various courts have ruled that state laws restricting political speech infringed on those rights. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the landmark 2010 Citizens United case that corporations, too, had a right to free speech and campaign donations, making some state efforts even murkier.

“Requiring truth makes a lot of sense, but enforcement of what is true is a contested thing these days,” said Michael Franz, a professor of government and legal studies at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine. “It’s important for states to consider these things, but the nitty gritty is where it gets tough.”

Consider Montana, one of the nation’s least populous states. For years, the state has tried to limit the influence of money in politics, and this year the U.S. Supreme Court left in place a new Montana law limiting campaign donations.

Also this year, two weeks after Dudik’s bill failed in the House, Democratic state Sen. Jen Gross wrote a bill of her own using similar language. Then, after seeing her legislation tabled in committee, she used a procedural maneuver to force a vote in the full GOP-led Senate. The bill passed.

But she couldn’t get a vote in the House when Republican Speaker Greg Hertz said the bill violated chamber rules because it had “the same purpose” as a bill that had recently failed.

Republican state Rep. Forrest Mandeville said the legislature should stop “banging our head against the wall” on an issue that is “blatantly unconstitutional.”

“Every two years, the legislature makes a few tweaks to it, and every two years the court throws it out,” he said. “I don’t think it does any good to pass an unconstitutional bill so that a couple members can feel good about themselves.”

While the Federal Trade Commission requires some truth in commercial advertising, there is no federal regulation for truth in political advertising. And states have had mixed results in their efforts.

As of 2014, 27 states prohibited certain kinds of false statements, according to the most recent tally by the National Conference of State Legislatures, which tracks state laws. Some states make it illegal for candidates to lie about endorsements, veteran status or incumbency.

Since then, courts have struck down laws in four of the states: Kentucky, Massachusetts, Minnesota and Ohio.

In 2016, for example, the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals found unconstitutional an Ohio law that banned campaigns and candidates from spreading false statements. “Even false speech receives some constitutional protection,” Chief Judge R. Guy Cole Jr. wrote in his decision.

But David Schultz, a professor of political science at Hamline University and a professor at the University of Minnesota School of Law, said he thinks that the First Amendment does not protect lying in politics and that there are constitutional limits to free speech.

Why, he asked, can’t states implement a check on candidates and political action committees who are “essentially lying or significantly distorting” voting records?

“The structural integrity of democracy is people telling the truth and playing fairly,” Schultz said. “If we don’t have that in place, the system collapses.” A substantial percentage of candidates and outside groups already footnote claims they make in ads against candidates with specific bills, quotes or media sources, said Bowdoin’s Franz, who is also co-director of the Wesleyan Media Project, which tracks political advertisements.

“The presumption is that they make the claims more powerful if there’s supportive evidence in the ads,” Franz said. “But it comes with a big caveat that claims made with supportive evidence still may not be true.”

Several states have attempted in the last two years to tighten rules for online political advertising.

California, Maryland, New York and Washington state crafted new transparency laws for digital political advertisements in the wake of Russian social media interference during the 2016 presidential election.

But once again, courts have pushed back against these efforts. In January, a federal judge ruled that Maryland’s law that regulates political ads on social platforms violates the First Amendment.

States have had some successes: In December, Facebook announced it would stop displaying political ads in Washington after the state sued the social media company and Google in June, accusing them of violating campaign finance rules for maintaining records. Earlier last year, Google also paused political advertisements in Washington in response to the lawsuit.

David Keating, the president of the Institute for Free Speech, a Virginia-based organization that opposes campaign finance limits, said the latest legislative attempt in Montana is just “another example of legislatures trying to commandeer other people’s speech for their purposes.”

“I find it objectionable—period—that they would seek to regulate the content of speech,” he said. “The courts have clearly said that the government is not the speech police.”

The current system for political advertising, under which campaigns and groups conform to different broadcasters’ standards, works well, he said.

Instead of regulating speech, the best way to counter negative ads about a candidate is by producing an ad in favor of that candidate, providing enough information for voters to seek the truth, he said.

If legislation were to pass in Montana, said state Commissioner of Political Practices Jeff Mangan, the chief campaign finance enforcement official, he “fully expects” the law to be challenged right out of the gate. He’s not optimistic that courts would support the proposed restrictions.

“I don’t see the courts changing their minds any time soon,” Mangan said.

Even so, that will not stop Dudik, the Montana Democrat who is now running for state attorney general, from trying once again to regulate political advertisements in her state.

This week, she introduced a new bill. Instead of requiring specific information on the actual attack ads, she said, the legislation would require candidates and groups to file supporting evidence for attack ads with the commission of political practices, which would then make the information available online for residents.

“We require truth in advertising in everything else,” Dudik said. “I don’t know why we shouldn’t have it in our campaigns.”