Church Scores Federal Court Win in Zoning Dispute With Village

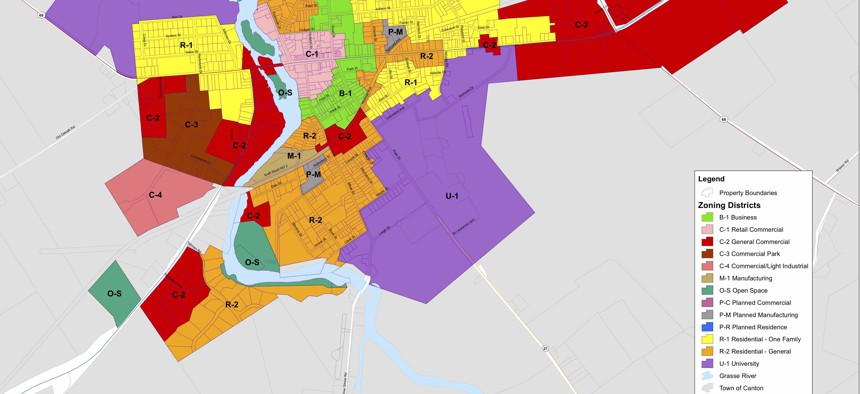

The zoning map for the village of Canton, New York. Village of Canton

The case involved religious discrimination claims and attracted the attention of the Justice Department.

A federal judge has blocked a village in northern New York from enforcing local zoning regulations that prevented a church from using a building it bought in a commercial district as a place of worship.

The case, which pits the village of Canton against a church known as Christian Fellowship Centers of New York, Inc., hinges in part on a federal statute that shields religious institutions from discrimination under zoning and landmarking laws.

John Mauck, a lawyer for Christian Fellowship Centers, said the church held services in the building at the center of the court dispute this past Sunday. “They didn’t have to do anything except move some folding chairs in and move their equipment in,” he said.

The Department of Justice weighed in on the case last week, siding with the church.

What will happen next isn’t entirely clear. The order issued last Friday by U.S. District Court Judge Lawrence Kahn, in the Northern District of New York, granted a preliminary injunction pending further proceedings, but also says the church is likely to prevail in the case.

“We’re hoping we can wrap the case up with a permanent injunction, or an agreement with the city of some type,” Mauck said.

“The church tried to tell the city, we tried to tell the city, DOJ tried to tell the city, the judge is telling the city, hopefully they’ll get the point, that it’s alright to allow people to worship in this particular location.”

A lawyer for the village did not respond to phone and email requests for comment.

The church’s request for an injunction relied partly on what’s known as the “equal terms” provision of the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act, or RLUIPA.

This portion of the federal law says that a government can’t “impose or implement a land use regulation in a manner that treats a religious assembly or institution on less than equal terms with a nonreligious assembly or institution.”

Mauck points out that the law has been interpreted differently by different appeals courts, and a petition for the Supreme Court to hear an Ohio case involving it is currently pending.

But in the Canton case, Judge Kahn said the church is “likely to succeed under even the most demanding tests” of how the equal terms provision is applied.

The church filed its lawsuit over the zoning ordinance in February. Last year, it bought a three-story building for $310,000 located in the village’s “C-1” retail commercial zoning district. Previously the building was home to restaurants and bars.

Trouble began when Christian Fellowship Centers sought village approval to use it as a church. A zoning board of appeals concluded in January churches aren’t permitted in the C-1 zone.

Kahn in his court order runs through the village’s main arguments for why churches can be excluded from the district without violating RLUIPA’s equal terms provision.

One is that Christian Fellowship Centers knew there were no churches operating in the zone before buying its building and that it would have most likely been allowed to locate and operate a church in other types of zoning districts within Canton.

But Kahn says the alternative sites would only be relevant if the zoning ordinance were challenged on the grounds it imposed a “substantial burden” on religious uses of land, a reference to another aspect of the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act.

In contrast, the judge wrote, the equal terms provision of the law is violated whenever religious land uses are treated worse than comparable nonreligious ones.

The village also argued that because the zone is commercial, and the church is not, it could be lawfully excluded from the district.

And another issue, highlighted by the zoning board, was that New York law restricts its state liquor authority from issuing licenses to establishments where liquor is consumed on site, if the businesses are within 200 feet of a church or school.

The board reasoned that this state law allowed the village to treat the church differently from comparable assemblies that do not trigger the same restrictions for surrounding property.

But the judge rejected each of these positions as well.

He noted, for instance, that according to the village ordinance the C-1 zone was designed not only to promote commercial activity but also to provide an area for recreational and cultural facilities and allows for “nearly every other type of non-commercial secular assembly.”

As for the complications the liquor law could pose, Kahn wrote that RLUIPA does not permit localities “to single out religious assemblies for exclusion just because the state, by self-imposed laws favoring churches, made them uniquely burdensome to accommodate.”

He added that “even if the Village had compelling interests in putting some number of liquor outlets downtown and in separating them by 200-feet from churches—there is no evidence that the downtown area is too small to accommodate the desired mass of new bars.”

The church has said that the five businesses now within 200 feet of their building are a credit union, a law firm, a bank, an insurance agency, and a locksmith.

In requesting the injunction, Christian Fellowship Centers also made a claim under the Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause. Kahn didn’t address this because he said “the Church has a strong likelihood of success on the merits of its statutory Equal Terms claim.”

Mauck said Christian Fellowship Centers is pleased with how swift and thorough Kahn was in issuing the court order and is confident it will win the case. As it stands, the ball is in the village’s court, he added.

“Jesus said: ‘try and settle your disputes,’" he said, "and that’s what we really want to do.”

Bill Lucia is a Senior Reporter for Route Fifty and is based in Olympia, Washington.

NEXT STORY: The National Teacher Shortage is Worse Than Previously Thought, Researchers Say