A New System to Ensure Sexual-Assault Cases Aren’t Forgotten

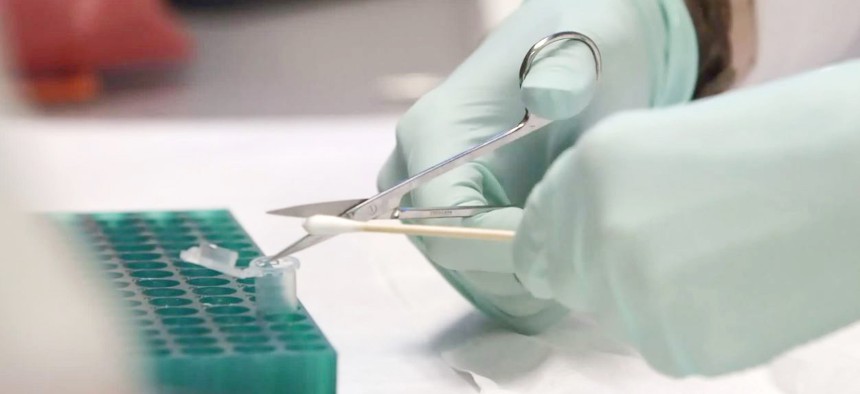

In a 2016 photo, the Idaho State Police Forensic Services lab tests for DNA samples. Idaho Press-Tribune via Idaho State Police via AP

Connecting state and local government leaders

More states are adopting software that allows sexual-assault survivors to track their evidence kits.

Susan Baisch has been conducting sexual-assault forensic exams for more than 27 years. Working as an emergency-room nurse for St. Luke’s hospital in Twin Falls, Idaho, Baisch has been specially trained to collect sexual-assault evidence in what are known as “rape kits.” The exam can be long and invasive, lasting four to six hours.

After assaults are reported, survivors’ bodies are treated like crime scenes and, if they so choose, searched, swabbed, and photographed, along with their clothes and other personal belongings, to find possible DNA evidence left by an attacker. Whatever evidence is found is then sealed in a sexual-assault evidence kit. The DNA can often be a crucial tool in prosecuting sexual assault. But that requires the kits to be tested by a police crime lab. Before 2016, forensic nurses didn’t always know what happened to the kits after they left their custody.

“We never really knew how many kits we had,” Baisch told me. She recalled that she would say to the police or the crime lab,“‘We sent you 10 last week—what happened to them?’” They didn’t always have an answer. And if the lab didn’t know, and the police didn’t know, and Baisch didn’t know, then the survivors themselves didn’t know.

Where did the kits go? Sometimes they were sitting in crime labs. Other times, they never even made it there. Investigative reporting by the Idaho Press-Tribune found that from 2010 to 2015, Twin Falls Police submitted only 23 percent of kits for testing. About 140 miles or so northwest of Twin Falls, in Nampa, only 10 percent of kits were submitted. This practice was not specific to Idaho. The Joyful Heart Foundation, an anti-sexual-violence nonprofit founded by the Law and Order: Special Victims Unit actress Mariska Hargitay, estimates that hundreds of thousands of sexual-assault kits are currently sitting untested in crime labs or police evidence rooms across the United States.

But the cycle was broken three years ago in Idaho. The state launched the first statewide sexual-assault-kit tracking system in the country. After their examination, survivors are now given their kit’s tracking number, like one they might get with a FedEx or UPS package. They can log into a portal that tracks their kit’s progress through the criminal-justice system. Survivors can see when the kit enters the custody of law enforcement. They can see when it’s sent to the lab for testing. They can see when DNA evidence is entered into the Combined DNA Index System, and when it comes back with a match. And if the kit stalls, they can advocate and push to have the test completed. The portal includes no names, to prioritize confidentiality, but using the tracking number, survivors, medical professionals, and law enforcement can all know the status of the kit. The law mandates that most kits must be preserved for 55 years. The kits will be tracked the whole time. Now law enforcement can prioritize kits whose cases are nearing the end of their statute of limitations. If a kit is taken from a survivor who doesn’t want to give her name, she is still given that kit’s tracking number. If she decides later that she wants to report the assault, she’ll be able to know where the evidence is.

From 2016, the first year of the Idaho Sexual Assault Kit Tracking System (or IKTS), to 2018, the number of DNA samples eligible for analysis in Idaho crime labs increased by 161.5 percent—both new and old sexual-assault kits were located and sent for testing. The Idaho State Police are required by law to issue an annual report on the tracking system. The state has now submitted all of its previously unsubmitted kits that were still eligible for testing, according to the 2018 report.

In 2015, only one state had a law for a sexual-assault-kit tracking system. Today, 17 states have tracking laws. And at least five more states are expected to launch them this year. Illinois announced plans on March 25 to have a tracking system by the end of the year. Ilse Knecht, the director of policy and advocacy for Joyful Heart, says states are starting to adopt tracking systems “because it makes so much sense.” Kit tracking provides a degree of transparency and accountability that, until now, had been notoriously absent from sexual-assault cases.

Idaho State Representative Melissa Wintrow proposed the state’s 2016 tracking-system bill. She worked with survivors of sexual assault for five years as Boise State University’s first full-time women’s-center director, and saw firsthand how difficult it can be for survivors who have experienced trauma to call the police and ask where their sexual-assault kit is. “But if you can go on a site at your leisure and see where it’s going, it’s empowering,” she said.

Annie Pelletier Hightower, the director of law and policy at the Idaho Coalition Against Sexual and Domestic Violence, said she’s “absolutely sure” that the tracking system is helping prevent a future backlog of sexual-assault kits. “We can now see what kits are outstanding, what kits have been processed, and then what’s been returned,” she told me.

The backlog issue has been gaining public attention since the late 1990s, when reporting revealed that labs were taking years to process the kits. Consider the case of Debbie Smith, who was assaulted in 1989. Her kit was not tested until 1995, six years after her attack. Smith’s advocacy after her assault helped raise awareness of the backlogs in crime labs, and led to the passage of 2004’s Debbie Smith Act, which granted federal funding to support the processing of DNA evidence.

In the 2000s, it became clear that untested kits weren’t just sitting in labs. They were piling up in evidence lockers, stashed in the trunks of police cars, or sitting, forgotten, in storage units. These kits had never made it to a lab, had DNA samples taken, or been brought to trial. In 2000, New York City had 17,000 untested sexual-assault kits gathering dust in a warehouse. A 2009 report by Human Rights Watch found that Los Angeles had at least 12,669 untested kits, unsubmitted to labs. The following year, Human Rights Watch completed a similar report on Illinois, which found that over the previous 15 years only 19.7 percent of kits could be confirmed as tested. “It was like, oh my gosh, how many are there?” Knecht told me. “Because nobody really was tracking, we didn’t know.”

Faced with a crisis, many states began to audit the number of sexual-assault kits through their law-enforcement system, a process that made some lawmakers begin to reevaluate how the kits were being handled. Back then, Knecht explained, most states were barely tracking the kits at all. “They might be keeping notes in a binder,” she said.“They might have an Excel sheet if they were really tech savvy.”

Across the country, lawmakers started to consider ways to address the problem. In 2015, Wayne County, Michigan, formed a coalition to brainstorm how to best address 11,000 untested sexual-assault kits discovered in a Detroit storage locker six years earlier. This coalition, led by the prosecutor Kym Worthy, eventually led Wayne County to pilot one of the first tracking systems. STACS DNA, a software company Michigan already employed to track DNA evidence in its crime labs, partnered with the state to develop the software Track-Kit, which is now used in at least nine Michigan counties (and in the summer will go live in the entire state), as well as in Texas, Arizona, Nevada, and Washington.

Captain Monica Alexander of the Washington State Patrol told me that every jurisdiction in Washington now uses Track-Kit, and said it’s going “really well.” She pointed out the importance of the system’s simple design. “You have very young rape victims, you have very old rape victims,” she said. “They wanted to make sure that anyone from any age group could use this.” She explained that if she called her IT department “right now,” someone could tell her the exact number of kits uploaded on any given day. Washington’s goal is to also upload all backlogged kits into the system—which right now number more than 4,000.

While some states buy software from private companies, Idaho built its system in-house. In 2015, the Idaho State Police put together a working group similar to the one formed in Michigan, including defense attorneys, prosecutors, sexual-assault-prevention advocates, medical professionals and law-enforcement officials. Wintrow met with this working group, and her legislation emerged out of their discussions. Matthew Gamette, the laboratory-system director of the Idaho State Police’s forensics service, then built the system with the help of department programmers. Gamette walked me through how to use the system; the software is simple in design and easy to navigate.

Now that the system is up and running, Gamette has offered to share it with any state that’s interested, free of charge. Many have taken him up on the offer: Since the system’s creation, Idaho has received inquiries about it from 25 states and three major cities. Some, including Utah and Arkansas, have then modeled their system on Idaho’s. Gamette has spent the past year working with other cities and states. When I spoke with him, he had just traveled to Puerto Rico to help establish a tracking system on the island. He explained that while he’ll give his system to anyone for free, he understands that some jurisdictions, especially the more populous ones, prefer using outside companies that have more resources, such as round-the-clock technical support.

While most tracking systems have been created through new laws, some have been created through regulation by law-enforcement agencies. New Hampshire, for example, received funding in January to establish a tracking system, but doesn’t have a law on the books. Knecht from Joyful Heart told me that while she views any tracking system as progress, she prefers that states create the systems with legislation to ensure that participation is mandatory.

Some states’ tracking systems exist only in specific jurisdictions. However, many advocates prefer tracking systems that cover entire states, so the location of an assault doesn’t affect survivors’ ability to track their kit. Scott Berkowitz, the president of the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network, or RAINN, said statewide networks make it easier for individual law-enforcement agencies to buy in. “If you do it on a state basis, then it’s clearer that it wasn’t a particular law-enforcement agency that screwed up; this is just sort of a systemic problem that everyone is dealing with,” he said.

Why have so many states started to tackle this issue at the same time? Berkowitz said the push may be because of the availability of federal funding through the Debbie Smith Act and 2012’s Sexual Assault Forensic Evidence Registry Act, which expanded on the Debbie Smith Act, and grants funding to end backlogs in both crime labs and police custody. A 2015 Department of Justice program, the Sexual Assault Kit Initiative, also provides funding to address the issue of unsubmitted kits, mainly for law enforcement and prosecutors. As of February 14, 35 states and 54 jurisdictions were using SAKI funding.

Berkowitz also pointed out that the hard work of advocates seems to have reached critical mass. “There’s a desire to once and for all try and get ahead of it,” he said. Shilpa Phadke, the vice president of the Women’s Initiative at the Center for American Progress, echoed the point that years of advocacy have helped push for the creation of these systems.

Phadke also pointed out that sexual-assault-kit testing is a relatively bipartisan policy for lawmakers to pursue, and law-enforcement departments, medical professionals, and public-safety officials all typically rally around it. However, she also believes there’s a lot more space for governments to try to fight sexual violence, and predicts there will be more movement soon on women’s issues. “I wouldn’t be surprised if we see, you know, a new round of very progressive governors coming in,” she said. “Making sure that the backlogs don’t happen again.”

Sophia Kerby, the deputy director of reproductive rights at the State Innovation Exchange, a progressive strategy center for state lawmakers, argued that broader reforms are still needed so that minorities feel more comfortable reporting sexual assaults to police in the first place. “The relationship communities of color, particularly black and brown folks, have with police makes it impossible for them to seek justice if it requires police involvement,” she said.

Still, she said, tracking is a positive first step. And for sexual-assault survivors in Idaho, it has made a real difference. Representative Wintrow recalled a time when a kit had been mislabeled, and because of the tracking system the survivor noticed and advocated to have the mistake fixed. Had she not been able to track it, her evidence may have continued through the system mislabeled. “It really shows it works,” Wintrow said.

“We’re trying to change the landscape nationwide of how crimes that affect mostly women and people who are gender-nonconforming are being dealt with,” Wintrow continued. “And we have to elevate those crimes to the top of the list, not the bottom.”

Madeleine Carlisle is an editorial fellow at The Atlantic.

NEXT STORY: Some Muslim Immigrants Distrust Census in Trump Era