The Rise and Fall of Thinking Big About Cities

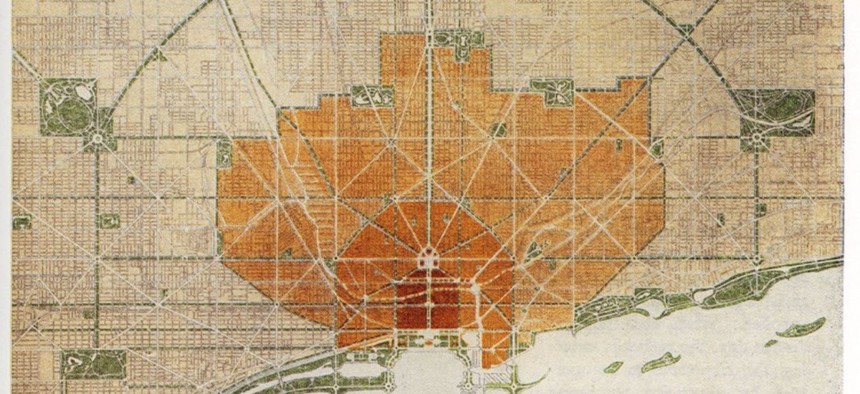

The 1909 Plan of Chicago, by Daniel Burnham and Edward H. Bennett, offered a comprehensive vision for controlled growth of the industrial metropolis. Harvard Libraries

A new exhibition looks back at the period of grand urban design and social reform in New York City, Boston, and Chicago.

This summer, visitors to Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum are being treated to a grand, thoughtful, and beautiful exhibition that explores the social-reform work of landscape architects, planners, photographers, and others active in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

“Big Plans: Picturing Social Reform” (on display through September 15) recounts the story of large-scale civic improvement plans in New York, Boston, and Chicago, and the dual births of the professions of urban planning and landscape architecture that emerged from these early successes.

Included is the usual cast of characters—Frederick Law Olmsted, his partner Calvert Vaux, landscape architect Charles Eliot, urban planner Daniel Burnham—and their projects in the three cities. Throughout the gallery one can detect the ever-present echo of Burnham’s famous commandment to “make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood and probably themselves will not be realized.” This was the period when America trusted in urban design to ameliorate pressing social problems, giving us the City Beautiful movement, park systems like Boston’s Emerald Necklace, and the institutions of the public museum and settlement house.

Maps, plans, renderings, archival records, and photographs tell the story. The first part of the exhibition focuses on proposals for the development of Manhattan, including a phenomenal 1811 engraving by William Bridges and Peter Maverick. With only the slightest variation of tone, the plan depicts both the existing city (below Houston Street) and an unvarying grid for future growth expanding clear to Harlem. The proposed grid is drawn in a bold hand—as a fait accompli, more real than the existing features. The planner draws what will be.

Paired with this plan is a later, more nuanced map: Egbert Viele’s 1865 “Topographical map of the city of New York,” which also includes this proposed grid, but superimposes it on the underlying topography and natural features of the island, including a number of brooks and streams surprising to those who never contemplated Gotham’s primordial state. Also present are more than a few farms and settlements in this “unbuilt” land, some to be lost to the promised wave of speculation and development, others to be removed in the name of conserving nature.

In the space between the two plans we begin to see the emergence of Central Park and the vision of a new sort of “big plan” which simultaneously preserves and engineers nature to shape the growing city.

The story continues through the examples of Chicago’s waterfront development and 1893 World’s Columbia Exhibition, and Boston’s famous Emerald Necklace. The Boston material is rendered all the more exciting thanks to the museum’s location in the heart of Boston’s Fenway district, an area transformed by Olmsted from a mucky backwater to a gemstone of natural beauty and civic edification. Isabella Stewart Gardner was one of the first to purchase land here for her museum, originally named Fenway Court. Gardner believed that personal encounters with art could improve society.

There is a second possible reading of “Big Plans” in the title of the exhibition. In addition to presenting visions grand enough to stir men’s blood (and spur their actions), the plans themselves—the physical drawings, maps, and renderings—are all stunning large-format prints, and the curators have been wise to provide these works of art with the gallery space appropriate to their stature.

In clever contrast, the final wall of the show features a series of comparatively diminutive photographs by Lewis Wickes Hine, a Massachusetts sociologist and photographer who, like Jacob Riis in New York, used his camera to document and publicize poor working conditions and slum life. (Hine’s photographs helped change public opinion regarding child labor.) Here, the smaller format delivers a refreshing human-scale intimacy to the subjects—mostly poor street children and struggling families—which requires the viewer to lean in and engage with the issues and human beings portrayed.

Time passes and things change. In the century since Burnham, the pendulum of public sentiment has largely swung away from these sorts of “big plans.” All too often, their siren-song beauty proved to conceal the violence and displacement that resulted from their eventual implementation. The generation reared in the aftermath of urban renewal and Robert Moses’s heavy hand developed a healthy skepticism toward large-scale visions. Today’s city residents and planners alike are more likely to channel E. F. Schumacher’s “small is beautiful” than to quote Burnham’s precept.

And yet large problems loom, and the exhibition may represent an honest and reflective moment to consider whether, and how, the pendulum may be swinging back again.

The curators resolve this tension through the words of another social reformer of the day. Upon first entering the gallery, visitors encounter a quotation from Frederick Douglass: “Poets, prophets and reformers are all picture-makers ... They see what ought to be by the reflection of what is, and endeavor to remove the contradiction.” Acutely aware of the power of social science, planning, and reform, as well as of their problematic legacies, Douglass reminds us of the need for vision, but also the importance of using that vision to confront and correct—not conceal, ignore, or relocate—the ugliness of reality.

The exhibition invites audiences “to consider the role of urban landscape in their own lives, including how sharing images of parks on social media contributes to the shared history of public spaces.” It closes with a short looping film produced by East Boston’s Windy Films, featuring contemporary artists, social activists, and design experts. Beyond the gallery, the museum is working to connect this project with its “Map This” outreach effort, including workshops with local artists and youth organizers to explore and interpret the communities of Boston through the creation of alternative maps.

Ezra Haber Glenn is an urban planner and lecturer at MIT's Department of Urban Studies & Planning.

NEXT STORY: How Disaster Warnings Can Get Your Attention