What Will Local Government Look Like in Space?

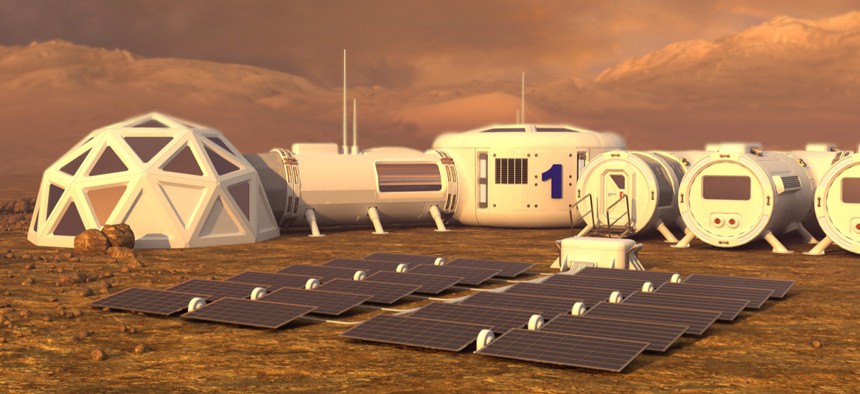

An illustration of what a Mars colony could look like. Shutterstock

Connecting state and local government leaders

Lessons from early American colonies might provide best practices and cautionary lessons for future settlements on other planets.

As both private companies and governments around the world inch closer to the possibility of creating human settlements on other planets, some are beginning to wonder what the makeup of those settlements will look like—and, more specifically, what kind of government those first intrepid explorers could create.

When considering how to structure society on Mars or elsewhere, Craig Calhoun, a professor of social sciences at Arizona State University, offered a few possibilities. “Are space communities to be modeled on idealized small towns?” he asked. “Or on resettlement camps for refugees? Or mining camps with overwhelmingly male populations that do hard labor?”

The possible self sufficiency of those space communities will have a large impact on what government looks like, Calhoun said at an event held this week by the JustSpace Alliance and Future Tense, a project that explores emerging technologies. And just because the communities are self sufficient, doesn’t mean they’ll be utopias. “It’s a red herring to say ‘space is empty, therefore there won’t be any issues of dominance or exploitation.’ Europeans brought slaves to America, and the same thing can happen again analogously in space. The potential for forced migration and labor are large,” he said.

Calhoun’s fears over the potential for space communities that are plagued by inequality or other social problems are partially based in historical examples from the founding of American colonies. Russell Shorto, a contributing writer at the New York Times Magazine, illustrated the parallels between the founding of New Netherland, which in the 1600s formed the basis of modern New York City, and future space settlements. “North America for [early explorers] might as well have been space,” he said. “There was a sense that it didn’t matter what people did. Laws and morals didn’t necessarily have to apply over there.”

New Netherland may be a particularly apt comparison to a Mars colony because it was originally founded under the auspices of a corporation, much as a company like SpaceX may very well be the first to create a new settlement in space. The residents of New Netherland eventually petitioned the government of the Netherlands to take a stake in the government of North America when they felt they had no say in the direction of the colony.

“Nation states had ceded governments to corporations,” Shorto said. “I don’t know where that behavior would take us in the limitlessness of space.”

One way to combat a do-over of the profound flaws of the colonial experience would be to think about government early on, said Bina Venkataraman, the director of global policy initiatives at the Broad Institute of Harvard & MIT. “When we imagine space settlements right now, we see a lot of examples of the infrastructure, how people are going to grow food and breathe,” she said. “All of that is important from an engineering point of view, but we have to include the issues of governance in that vision as well.”

The structure of any government would likely be determined by why people leave Earth in the first place, she said. “Is leaving an escape for the elite or is it an eviction for people who can no longer use the resources on earth?” she asked. Factors like that could determine how much public space is created in other worldly settlements, or how property rights are set.

Space settlements would likely be part of a larger international system that answers some of these questions. The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 has already stipulated that no nation can establish sovereignty on any celestial body. But while territory can’t be officially claimed, the U.S. has pushed to allow companies greater rights in space. The Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act of 2015, designed to encourage companies to fund expensive space exploration missions, granted corporations the rights to objects they obtained in space, potentially opening the door to intergalactic mining.

The issues that arise from allowing mining in areas seen as international common space have already been shown here on Earth on the continent of Antarctica. Unlike other similarly barren parts of the world, Antarctica has no native population, and is not governed by any particular country, so standards there are largely set by international agreements.

Officially, under the Antarctic Treaty of 1961, the continent is a scientific preserve. Though seven countries have territorial claims, some of them overlapping, other countries do not recognize these claims, and any attempts to establish rights of sovereignty or conduct military activity are technically banned. Prospecting for minerals and drilling for oil are also banned, but the 54 states that have ratified the treaty will have to re-agree to these terms in 2048, when the protocol is up for renewal.

Before that issue comes before an international vote, though, military expansion on the continent by Chile and Argentina have some scientists worried the treaty is losing its consensus support, possibly leading to a physical or diplomatic war for control of Antarctica.

A scenario like that might be less likely to play out in space, simply because few countries have the resources to send government officials or military personnel there. But whatever settlement arises in space—if one ever does—will face local governments challenges entirely unique to their conditions.

Alex MacDonald, a senior economic advisor for NASA, said that the first local governments in space may struggle to impose control because they didn’t fund their arrival there. “We want these settlements to have autonomy, but they’ve probably been sent there by an entity that has a motive for sending them there,” he said. “That will be a challenge.”

Calhoun, expanding on the authority that local governments could seek in space, was more worried about the possibility of disagreements of residents within a particular settlement, which would force local governments to create systems to allow residents to migrate between different space communities. “Local governments will have to confront a difficult degree of enclosure,” he said. “There’s always somebody who will want to go elsewhere. How to deal with that will be a big question for the governments.”

Emma Coleman is the assistant editor for Route Fifty.

NEXT STORY: Many College Students Are Too Poor to Eat