On-Site Health Care Could Help Seniors Stay at Home

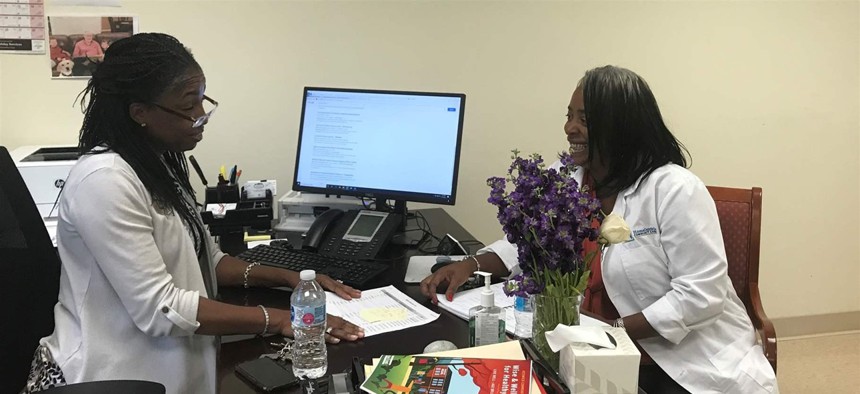

Lisa Mears-Morris, left, and Latonya Gwynn go over resident files at Weinberg Villages, a housing complex for low-income seniors in Owings Mills, Maryland. The two are part of a national experiment aimed at helping seniors age in place. Pew Charitable Trusts

Forty affordable housing complexes are in an innovative federal program.

OWINGS MILLS, Md. — The “two super fantastic ladies”—as one resident calls them—at the Weinberg Villages senior housing complex are operating quasi-undercover. Sure, they serve up smiles, friendly chit-chat and treats for four-legged visitors. But while they’re smiling and talking to the residents here, they’ve really got an ulterior motive.

“I’m secretly picking them apart,” said Latonya Gwynn, the on-site nurse. Gwynn said she does a medical assessment mentally every time a resident comes into her office.

“We are the very nice ladies in the office,” said Resident Wellness Director Lisa Mears-Morris. “But the nice ladies are always doing their job.”

Since early last year, they’ve been ensconced here as part of a federal experiment, checking blood pressure, making sure residents are taking their medicine, encouraging them to exercise, showing them how to prevent falls, helping them sign up for food stamps, Medicaid and Medicare — even showing up for hospital visits.

“I don’t want to sound like we’re Mary Poppins and we’re doing something magical,” Mears-Morris said. “But we’re trying to help them age in place with the best quality of life.”

The nation’s older population is growing rapidly — it’s projected to nearly double by 2050. Many seniors want to stay in their homes, but when they grow older and more infirm, that isn’t always possible.

Nor are there enough services — access to transportation and doctors, help managing medication — to make it easier for them to stay at home, according to a 2017 report by the Office of Policy Development and Research in the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

A social services pilot program at Weinberg Villages in Owings Mills, Maryland, part of a three-year, $15 million federal experiment, could be one solution. The community is one of 40 affordable housing sites around the country participating in a demonstration program funded by HUD called IWISH — Integrated Wellness in Supportive Housing.

The program works to deliver health care services to low-income seniors in affordable housing developments so they stay out of emergency rooms and nursing homes. Participants get an individualized plan to improve their health, such as taking fall-prevention classes or working on weight loss or getting signed up for mental health care.

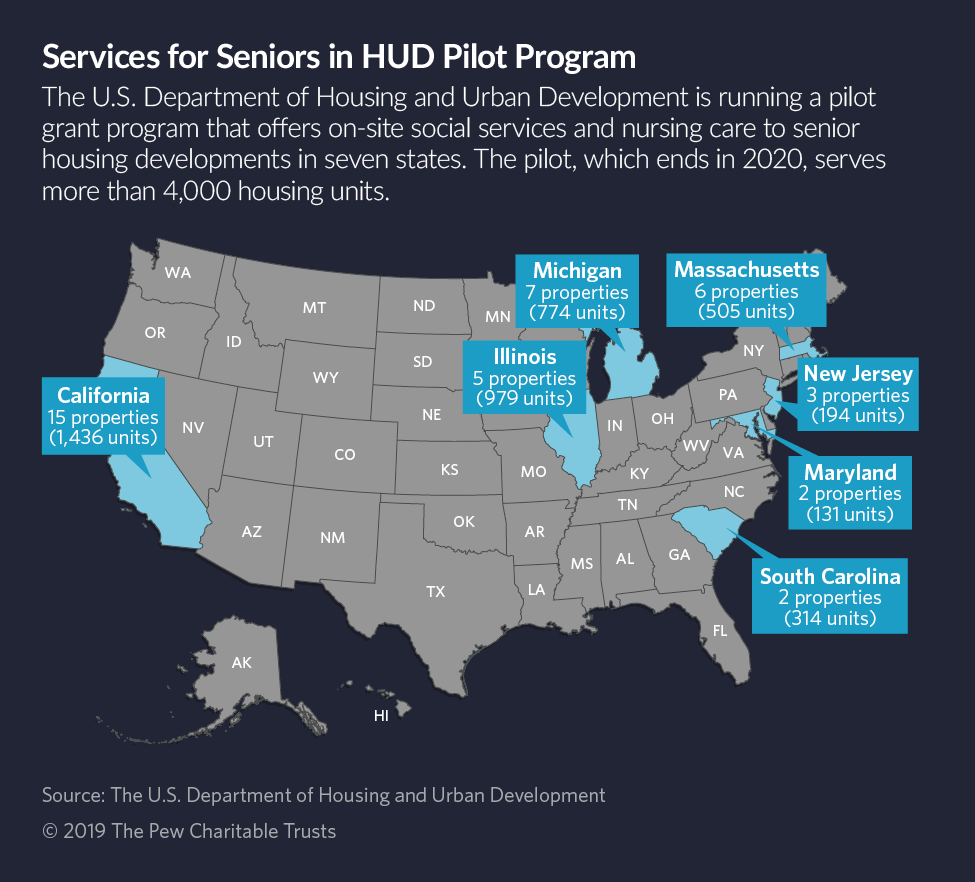

The pilot program brings service coordinators and health care workers to federally subsidized senior housing developments operated by nonprofits at sites in California, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey and South Carolina.

As at Weinberg Villages, each IWISH site has a full-time service coordinator and a part-time nurse.

“If you offer affordable housing with social services on-site, it will help [residents] both remain in their homes and reduce health care costs,” said Linda Couch, vice president of housing policy for LeadingAge, a research and advocacy group for seniors based in Washington, D.C., that is helping HUD implement the IWISH program.

“The question is, what will it take to scale these programs up to a national level?”

It’s not clear what will happen when the funding runs out in 2020; HUD officials wouldn’t answer Stateline’s questions about what comes next. But without further federal investments, senior advocates worry the pilot programs will shutter, nurses and caseworkers will be laid off, and seniors in those communities will have to find other ways to get the help they need.

“I worry about seniors needing higher levels of care and not being able to age in place,” said Janice Monks, president and CEO of the American Association of Service Coordinators, an Ohio-based coalition of caseworkers embedded with low-income housing developments. Many of the members are now working in IWISH programs around the country.

But while the IWISH model looks promising to many, it’s not without its challenges. Paying for it is the biggest barrier. IWISH uses HUD money, which is limited, to pay for on-site medical care, rather than Medicare and Medicaid, which cover anybody who qualifies.

If HUD doesn’t renew the pilot program after the money runs out next year, it will be difficult to find money for it in the private health market, according to Alisha Sanders, director of housing and services policy research at the LeadingAge LTSS Center at the University of Massachusetts, Boston.

That’s because residents typically have different insurance providers and health care providers, Sanders said. And health providers aren’t motivated to pay for wellness and prevention programs because the savings come down the road, she said.

Staffing, too, is a challenge, senior advocates say. Nurses are in high demand and hospitals and health systems generally pay more than residence-based programs like IWISH.

Another challenge: Some residents look askance at the prospect of signing up for on-site services, service coordinators say. Some don’t want their landlords to know their personal business. Others think they don’t need help. Others fear asking for help means they could end up in a nursing home.

But asking for — and getting — help can mean the difference between staying in their homes or ending up in a nursing home or an acute rehab facility, Gwynn said.

“One fellow told me to stop asking about his health,” Gwynn said. “But I really need you to tell me if you fell.”

Living Independently

The IWISH programs run in senior affordable housing complexes subsidized with HUD funding. At Weinberg Villages, there are five buildings on the campus, but only one is participating in the demonstration program. The goal is to enroll 80% of the residents in that building; so far, 33 people have signed up out of 75 units in the building, according to Mears-Morris.

On a recent September afternoon, a woman in an electric wheelchair rolled up and popped into the doorway of the health office.

“Can I get a flu shot if I’ve got a cold?” she asked.

“Nope,” Gwynn told her. Satisfied, the woman zipped off.

HUD created the IWISH model to help seniors live independently for as long as possible, said Calvin Johnson, deputy assistant secretary for HUD’S Office of Research, Evaluation and Monitoring. (HUD spokesman Brian Sullivan would not comment about IWISH’s future funding.)

“Our folks [in federally assisted housing] have costly health care expenditures,” Johnson said. “They have [health] conditions that are chronic and severe. We peeked into the data to see what we needed to do to focus on health to arrest these conditions.”

To address the problem, HUD looked to an eight-year-old Vermont program called SASH, for Services and Support at Home, which connects residents in affordable senior housing with an on-site team that includes a service coordinator and a wellness nurse.

The program is operated by 22 affordable housing complexes around the state, paid for through a mix of federal and state funding. More than 6,000 people with an average household income of about $16,500 are enrolled in the program. Over the past couple of years, they’ve opened a SASH program in Providence, Rhode Island, and in St. Paul, Minnesota.

When the program first launched, one of the biggest challenges was getting health care providers to recognize that low-income housing organizations could play a role in improving health outcomes for the elderly, said SASH Director Molly Dugan.

“But health behaviors happen at home,” Duggan said. “We’re able to provide the health coaching, the care coordination and build trusting relationships that allow for real change to happen.”

Research shows promise: A HUD report last year found that urban counties participating in SASH experienced a slower growth in total Medicare expenditures as well as expenditures for hospital care, emergency department visits and specialist physician visits compared to a control group.

Meanwhile, a July report by U.S. Department of Health and Human Services found that some SASH locations in urban areas reduced Medicare costs by as much as $1,450 per person annually, mostly through reducing hospital visits. But rural locations had less success. The report also found the program helped seniors stay in their homes and out of nursing homes.

Other localities have experimented with similar approaches, but on a much smaller scale, in Pittsburgh; Portland, Oregon; and Queens, New York.

Meanwhile, Sanders of the LeadingAge LTSS Center is conducting an evaluation of similar programs offered by 2Life Communities in Boston. With funding from the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission, 2Life operates six communities around Boston using what it calls a “village center” model.

Later this year, HUD will release its preliminary findings on the success of the IWISH pilot — whether it helped seniors age in place, avoid early admissions to nursing homes and prevent unnecessary emergency room visits.

Researchers will compare outcomes from the 40 IWISH sites against 84 affordable housing sites around the country that don’t offer the on-site health and social services care, said Leah Lozier, a social science analyst with HUD.

“We want to really understand what’s easy, what’s hard, what works and what doesn’t,” she said.

‘It’s a Visit’

Before the IWISH program got its start at Oakland, California’s Allen Temple Arms housing development last year, its older residents often ended up in the emergency room or the hospital.

“There are a lot of residents who used to call 911 just to cuss,” said Donna Griggs Murphy, the site’s social services coordinator. Often, they were lonely and just wanted attention, she said, and would call the fire department about everything from trash pickup to a lack of supplies to manage their incontinence, she said.

“Can you imagine?” Murphy said. “You’ve got this big strapping fireman coming to your house. It might be the only visit you have all week. It might be a negative visit, but it’s a visit.”

When the program started, its managers enlisted the help of some of the more outgoing residents to spread the word about the program. Now, out of 121 residents, 90 have signed up, Murphy said.

Caregivers provide each resident with an individual healthy aging plan that includes an exercise regimen and assistance managing medication. But Murphy worries that she’ll run out of time before she can really make a difference in their lives.

“It takes just a year for people to get to know you, to trust you, to tell you intimate things,” she said.

Teresa Wiltz is a staff writer for Stateline.

NEXT STORY: Weighing What Congress Could Learn From State Legislatures