Why Community-Owned Grocery Stores Like Co-ops are Better at Revitalizing Food Deserts

The food trust financed dozens of supermarket projects in Pennsylvania in 2004. AP Photo/Matt Rourke

COMMENTARY | Walmart and other major retailers vowed to build hundreds of stores in food deserts. What happened?

Tens of millions of Americans go to bed hungry at some point every year. While poverty is the primary culprit, some blame food insecurity on the lack of grocery stores in low-income neighborhoods.

That’s why cities, states and national leaders including former first lady Michelle Obama made eliminating so-called “food deserts” a priority in recent years. This prompted some of the biggest U.S. retailers, such as Walmart, SuperValu and Walgreens, to promise to open or expand stores in underserved areas.

One problem is that many neighborhoods in inner cities fear gentrification, when big corporations swoop in with development plans. As a result, some new supermarkets never got past the planning stage or closed within a few months of opening because residents did not shop at the new store.

To find out why some succeeded while others failed, three colleagues and I performed an exhaustive search for every supermarket that had plans to open in a food desert since 2000 and what happened.

What's a Food Desert?

I’m actually rather skeptical that food deserts have a significant impact on whether Americans go hungry.

In previous research with urban planners Megan Horst and Subhashni Raj, we found that diet-related health more closely correlates with household income than with access to a supermarket. One can be poor, live near a grocery store and still be unable to afford a healthy diet.

Nonetheless, the lack of one, particularly in urban neighborhoods, is often a broader sign of disinvestment. In addition to selling food, supermarkets act as economic generators by providing local jobs and offering the convenience of neighborhood services, such as pharmacies and banks.

I believe every neighborhood should have these amenities. But how should we define them?

U.K.-based public health researchers Steven Cummins and Sally Macintyre coined the term in the 1990s and described food deserts as low-income communities whose residents didn’t have the purchasing power to support supermarkets.

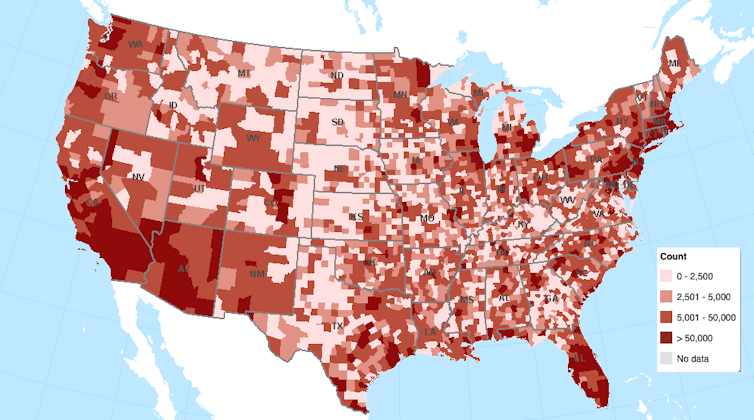

The U.S. Department of Agriculture began looking at these areas in 2008, when it officially defined food deserts as communities with either 500 residents or 33% of the population living more than a mile from a supermarket in urban areas. The distance jumps to 10 miles away in rural areas.

Although the agency has created three other ways to measure food deserts, we stuck with the original 2008 definition for our study. By that measure, about 38% of U.S. Census tracts were food deserts in 2015, the latest data available, slightly down from 39.4% in 2010.

That means about 19 million people, or 6.2% of the U.S. population, lived in a food desert in 2015.

Michelle Obama Makes It a Priority

The Food Trust was among the first to tackle the problem. In 2004, the Philadelphia-based nonprofit used $30 million in state seed money to help finance 88 supermarket projects throughout Pennsylvania, which helped make healthy food available to about 400,000 underserved residents.

Our research followed the success as it drew attention nationally. Rahm Emanuel made eliminating food deserts in Chicago a top initiative when he became the city’s mayor in 2011. And Michelle Obama helped launch the Healthy Food Financing Initiative in 2010 to encourage supermarkets to open in food deserts across the country. The following year major food retailers promised to open or expand 1,500 supermarket or convenience stores in and around food desert neighborhoods by 2016.

Despite receiving generous federal financial support, retailers managed to open or expand just 250 stores in food deserts during the period.

How to Grow in a Food Desert

We wanted to dig deeper and see just how many of the new stores were actually supermarkets and how they’ve fared.

I teamed up with Benjamin Chrisinger, Jose Flores and Charlotte Glennie and examined press releases, website listings and scholarly studies to assemble a database of supermarkets that had announced plans to open new locations in food deserts since 2000.

We were particularly interested in the driving forces behind each project.

We identified only 71 supermarket plans that met our criteria. Of those, 21 were driven by government, 18 by community leaders, 12 by nonprofits and eight by commercial interests. Another dozen were driven by a combination of government initiative with community involvement.

Then we looked at how many actually stuck around. We found that all 22 of the supermarkets opened by community or nonprofits are still open today. Two were canceled, while six are in progress.

In contrast, nearly half of the commercial stores and a third of the government developments have closed or didn’t it make it past planning. Five of the government/community projects also failed or were canceled.

A shuttered supermarket is more than just a business failure. It can perpetuate the food desert problem for years and prevent new stores from opening in the same location, worsening a neighborhood’s blight.

Why Co-ops succeeded

So why did the community-driven supermarkets survive and thrive?

Importantly, 16 of the 18 community-driven cases were structured as cooperatives, which are rooted in their communities through customer ownership, democratic governance and shared social values.

Community engagement is vital to opening and sustaining a new store in neighborhoods where residents are understandably skeptical of outside developers and worry about gentrification and rising rents. Cooperatives often adopt local hiring practices, pay living wages and help residents counteract inequities in the food system. Their model, in which a third of the cost of opening typically comes from member loans, ensures communities are literally invested in their new stores and their use.

The Mandela Co-op, which opened in a West Oakland, California, food desert in 2009, is a great example of this. The worker-owned grocery store focuses on purchasing from farmers and food entrepreneurs of color. As a result of its success, the Mandela Co-op is expanding and supporting the local economy at the same time many commercial supermarkets are closing locations as the grocery industry consolidates.

Our study suggests policymakers and public health officials interested in improving wellness in food deserts should take community ownership and involvement into account.

The success of a supermarket intervention is predicated on use, which may not happen without community buy-in. Supporting cooperatives is one way to ensure that shoppers show up.

Catherine Brinkley is an assistant professor of community and regional development at University of California, Davis.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

NEXT STORY: 'Gravely Disabled' Homeless Forced Into Mental Health Care in More States