Red Flag Laws Spur Debate Over Due Process

Guns on display at a gun show in Wisconsin. Keith Homan/Shutterstock

Some critics say the increasingly popular gun laws are unconstitutional.

This article originally appeared on Stateline, an initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts.

In the year since Florida enacted its red flag law, Kendra Parris has defended nearly 20 clients against risk protection orders that could remove their firearms.

The Orlando-based lawyer has long represented people who might be subject to the state’s involuntary mental health treatment provision. But when this new law, meant to protect against people who might be a harm to themselves or others, passed in the aftermath of the February 2018 Parkland mass shooting, she saw yet another opportunity for the state to potentially deprive certain people of their civil liberties.

“It’s almost like a shiny new toy for law enforcement,” Parris said, “filing them left and right.”

Since the law’s adoption, Florida courts have approved around 2,500 risk protection orders, according to an August count by NPR.

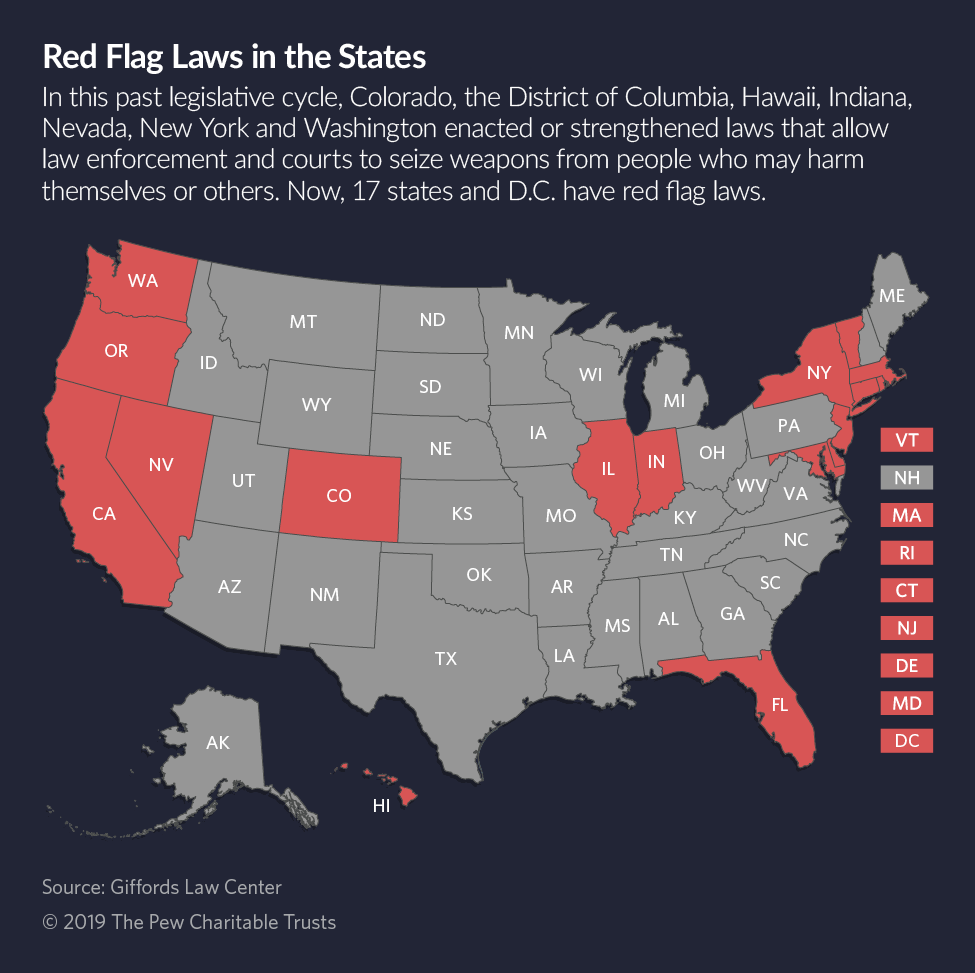

Since Parkland, at least six states and the District of Columbia have passed red flag laws, which allow law enforcement agencies that have gotten a court order to remove guns from people considered a harm to themselves or others. In the wake of high-profile shootings this summer in Ohio and Texas, including one that killed eight people in Midland-Odessa this past weekend, more state lawmakers are considering such laws, as are some members of Congress.

Many law enforcement officials firmly believe the laws save lives, and lawmakers say they can craft legislation that won’t infringe on civil liberties.

But for two decades, since the first such law was enacted in Connecticut, civil and gun rights advocates have protested that the seizures violate the U.S. Constitution’s due process guarantee — meaning residents have a right to fully argue their case in court.

“Rather than find clear and convincing evidence, [courts are] basically saying, ‘Better safe than sorry,’” Parris said.

Most red flag laws are vague on what constitutes a “significant danger,” which gives courts broad discretion to seize firearms, Parris said. And in some states, respondents are not guaranteed representation in court, since these are civil and not criminal matters.

Many defense lawyers say respondents fare much better with legal representation. Of Parris’ seven cases that have gone to a hearing, she has won five — which she said is a “vastly higher” success record than when someone represents themselves.

Due Process Concerns

Seventeen states and D.C. have laws on the books that allow law enforcement or family members to petition courts to remove weapons from people who may be dangerous and prevent them from buying other weapons for up to a year. In many of these states, bipartisan groups of lawmakers led the drive to pass the legislation.

States define “red flags” differently, but they largely follow the same process for taking away somebody’s guns.

If someone is showing signs of erratic behavior or expressed some intent to hurt themselves or others, they might be subject to an extreme risk protection order. In most states with red flag laws, family or community members can petition a court for those orders. But in Florida, Rhode Island and Vermont, law enforcement officials are the only ones who can petition to remove firearms.

If there is an immediate risk of harm, a court can issue a temporary ex parte order to seize guns from people for up to 14 days in most states. Other states range from two days to 45 days. At those hearings, a judge can issue the order by listening to evidence from the petitioner.

In many cases, the subject of a petition can’t present a defense until the final hearing. But that’s where the process gets legally dubious to some critics.

Dave Kopel, research director at the Independence Institute, a Denver-based libertarian think tank, said states have taken the same approach President Donald Trump spoke in favor of in March 2018: “Take the guns first, go through due process second.”

When it comes to seizing guns through a temporary order, the standards that a judge uses should be high, Kopel said. Vermont, he believes, has a fair system, which requires “specific facts” that show “an imminent and extreme risk.”

The situation becomes even more precarious when loved ones can petition for the removal of firearms, he said. Spurned former partners or family members seeking revenge might “weaponize” this tool, he said. Because of that, he argues, there should be a penalty for maliciously false accusations, which several states have adopted.

But New York state Sen. Brian Kavanagh, a Democrat and the author of the state’s red flag law that went into effect last month, said family members and former partners are most likely to have evidence and an urgent need for safety. The Empire State even added school officials to the long list of potential petitioners.

The New York law requires enough due process, he said, including an appeals process, a prompt evidentiary hearing and a burden on the petitioner to meet a certain standard of evidence.

“We think we’ve gotten the balance right,” Kavanagh said. “This is the government depriving people of their property. When you do that, you have to be careful. And we think we have.”

In some states, lawmakers modified legislation to address due process concerns before the final votes.

In Rhode Island, the American Civil Liberties Union originally came out against the state’s 2018 measure until the legislature tightened the standard for granting a petition, created penalties for providing false evidence of a threat, allowed only law enforcement to file petitions, required specific evidence and granted the right to legal counsel in hearings.

After these changes, the group shifted its stance to neutral on the bill, dropping its main objections, said Rhode Island ACLU Executive Director Steven Brown.

“We believe it’s very important that basic due process standards are considered when drafting measures like this,” he said. “It can have serious impacts on innocent individuals.”

Still, some gun rights activists reject the laws flat out. Mark Pennak, president of Maryland Shall Issue, a gun rights group that has opposed many of the recent gun control measures adopted in the state, including a ban on bump stocks and the red flag law, said he’s concerned about future abuses, including officers taking away guns “just to be sure.”

“My concerns have gotten worse,” Pennak said. “People are being legally traumatized.”

‘No Perfect Law’

Red flag laws have emerged as one of the most common responses to mass shootings across the country in recent years.

At least five more states, including deeply red Kentucky, have bipartisan bills under consideration. Polls show that Americans widely support the policy — even by as much as 77%, according to an August poll by American Public Media Research Lab.

While it’s difficult to know how many shootings might have been prevented through these court orders, news reports from around the nation show that courts and local law enforcement agencies have been able to use the laws thousands of times. Law enforcement officials have been clear: Many think these laws are saving lives.

For decades, Pinellas County Sheriff Bob Gualtieri and other Florida law enforcement officials would encounter people whose behavior didn’t rise to the level of a crime but who showed signs that they might be a threat.

There was nothing in state law, he said in an interview, that would have allowed law enforcement to remove guns or ammunition from a potentially dangerous home, until March 2018 when Florida enacted its red flag law.

“Now we can do something in those situations,” he said. Between March 2018 and March 2019, courts granted 233 risk protection orders in Pinellas County, according to state data. In that period, courts denied only one.

Gualtieri rejects some of the criticism over due process. The standard for removing weapons is high, he said, and requires “clear and convincing evidence.” His department has a five-person team dedicated solely to risk protection orders.

And when courts issue temporary orders, it’s only for a brief period, he said, and builds on existing laws on civil domestic violence restraining and protection orders.

“There is no perfect law,” Gualtieri said. “It doesn’t exist. But we are much better to make sure that the guns are not in the wrong hands. There’s nothing worse than a horrific situation that could well have been avoided.”

Future Fights

Red flag laws continue to enjoy nationwide momentum.

After three mass shootings last month — in Dayton, Ohio, in El Paso and Midland-Odessa, Texas — left at least 39 people dead, state and national leaders are once again hearing a chorus for action to prevent future gun violence.

U.S. Sen. Lindsey Graham, a South Carolina Republican, announced his intention last month to introduce bipartisan legislation with Democratic U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut. It would set up a grant program to assist states in adopting red flag laws.

Local law enforcement agencies could use those funds to hire and consult mental health professionals before issuing extreme risk protection orders.

But Graham, the chairman of the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, made sure to mention that new legislation would require “robust due process and judicial review.”

Red flag laws have survived two major legal challenges. In one case, the Connecticut Appellate Court found in 2016 that the state’s red flag law “does not implicate the second amendment, as it does not restrict the right of law-abiding, responsible citizens to use arms in defense of their homes.”

Since the Second Amendment was the focus in both cases, said Kopel of the Independence Institute, there is still room to address due process.

In Florida, attorney Kendra Parris has a case in the state district court of appeals, where she is defending a 16-year-old boy with autism who threatened to shoot his classmates after becoming agitated in class when a peer kept bumping into his desk.

School authorities notified local law enforcement, who later secured a temporary ex parte risk protection order.

In the process, Parris is arguing, the boy’s constitutional rights were violated. Parris is citing the law’s vague language, due process gaps and separation of powers issues: Local enforcement both conducted the investigation and decided whether the case should go to a hearing.

She thinks her case, which goes to oral arguments in October, might eventually make its way up to the Florida Supreme Court.

Matt Vasilogambros is a staff writer for Stateline.

NEXT STORY: Hurricane Dorian Is Not a Freak Storm