Smithsonian to Rural Regions: Your Wealth Is in Your Culture

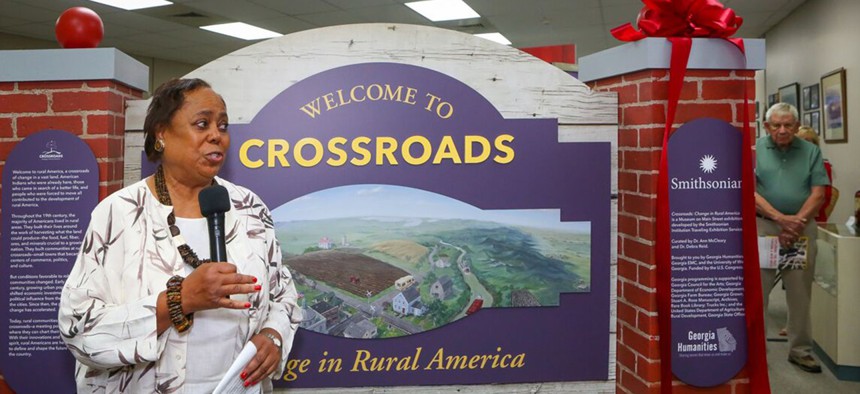

Brenda Gaines, a member of the Smithsonian Institution National Board and board chairwoman for the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service, speaks during the opening of “Crossroads: Change in Rural America” in Thomaston, Georgia, Aug. 24. Georgia Humanities/Rick Brozek

A traveling exhibit will visit up to 165 rural cities across 28 states.

This article originally appeared on Stateline, an initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts.

The day’s music included local favorites such as the Upson-Lee High School Marching Knights and color guard, a Southern gospel church choir and a barbershop quartet.

Children posed for photos in old tractors. Visitors to this Thomaston, Georgia, event took home old peach labels. A local farm set up a stand selling shredded collard greens, peach preserves, pickled peaches and homemade cakes, according to Lori Showalter Smith, president of the Thomaston-Upson Chamber of Commerce.

Central Georgia’s history and talent showed up for the opening of a traveling Smithsonian exhibit, and the hoopla around it, on a recent weekend, but the celebration did not gloss over local challenges.

Items on display from local archives highlighted industry, like the former Coca-Cola bottling company and the textile manufacturer Thomaston Mills, a century-old economic engine that reportedly laid off 1,400 after filing for bankruptcy 20 years ago. With the loss of industry came the loss of residents. Mom-and-pop shops shriveled up, Smith said.

“In the society that we live in, a lot of people have lost a sense of pride in where they come from, or whether they belong; just a sense of place,” Smith said. “To help restore that you should be proud that we have this history here, that the past exists, we’re bringing the Smithsonian into our community for everybody to enjoy and experience.”

Through 2024, the traveling exhibit, called “Crossroads: Change in Rural America,” is going to the center of the action: up to 165 rural cities across 28 states. In collaboration with state humanities councils, it aims to foster conversations in rural communities, encourage a focus on local history and artistic expression, build community spirit and stress cultural diversity. Communities are urged to host events that encourage videographers, youth and students to capture and celebrate local stories.

The exhibit covers big themes like identity, land, community and persistence using artifacts, multimedia displays, community discussions and works by local artists. The curators behind Crossroads and similar efforts want rural communities to consider their cultural assets when devising solutions to challenges ranging from economic downturns to education hurdles—despite a broader national narrative that typically emphasizes what such communities lack.

“These communities have wonderful things about them,” said Susan DuPlessis, director of community arts development for the South Carolina Arts Commission. “A lot of times, though, when we’ve been told over and over that we ‘have nothing,’ then you start to believe it and you forget to see what you have all around you. Or fail to understand that the local barbershop where the men go and tell stories about community is a local treasure.”

‘It’s Not About GDP’

The exhibit has six free-standing sections that take up about 750 square feet. In Thomaston, it’s housed at an old Thomaston Mills building, while in other cities it may be in the local historical society, arts center or public library. Themes and accompanying descriptions are meant to prod the viewer to consider questions such as, “How have rural communities and small towns evolved and changed? Why and how are people holding on in their rural communities? What is rural life like today? How are rural Americans shaping their future?”

The story around rural America often emphasizes deficits, such as out-migration, lack of education, poor access to health care and high rates of poverty. Given the slow decline of agriculture and manufacturing, and the boom and bust cycles of economic activity around extractive industries, many rural communities suffer from low levels of civic engagement, weaker social networks and isolation, according to rural affairs scholars.

Those challenges exist, but focusing on them disregards the diversity within rural regions, according to a comprehensive description of rural wealth developed by the Rural Policy Research Institute, based at the College of Public Health at the University of Iowa.

The Smithsonian exhibit, which was developed in coordination with the Iowa research institute, and similar efforts aim to reframe rural wealth beyond economic measures to include intangible assets, such as natural resources, social networks, cultural practices and population sparsity.

“It’s not about GDP; it’s not about how much money you make; it’s about people,” said Carol Harsh, director of Museum on Main Street, the Smithsonian’s traveling exhibition service.

For example, Thomaston, population 8,740, isn’t hustle and bustle, but that’s how people want it, said Smith, from the Thomaston-Upson Chamber of Commerce.

As residents of an old mill town, folks are resilient, Smith said. They proudly display their Christmas lights on Christmas Lane, a stretch of residential homes that light up around the holidays. The annual Chitlin Hoedown in Upson County’s Yatesville draws visitors from across the Peach State.

Living in a rural area with a small population was among the main reasons Smith wanted to bring the exhibit to Upson County. “We have a lot of people in this community, including students, that will never leave Upson County, much less go to where a Smithsonian is being held or D.C.”

The exposure gleaned by the exhibit can help attract new residents, Smith added. “My overall hope is that people will come to Thomaston and make the conclusion that this is where they want to be.”

Several identical exhibits are traveling the country simultaneously. They cover rural communities broadly and don’t focus on any one region. The exhibit opened in Moscow, Idaho, on Aug. 23, and Thomaston on Aug. 24. On Sept. 7, it was set to open in Dundee, Michigan; Dillsboro, Indiana; and Lafollette, Tennessee.

For Dulce Kersting-Lark—executive director of the Latah County Historical Society in Moscow, where the traveling Smithsonian exhibit is housed at the chamber of commerce—rural wealth means capitalizing on the things that make a region special.

“There is real economic power in nostalgia,” Kersting-Lark said. “I don’t want to misconstrue the idea that we’re all Pollyanna and everything is hunky dory. We know that it’s not and there is room to grow, but there’s also value in living in a place that’s not as congested, and people will pay for that value.”

Thomas Jefferson’s agrarian dream, for example, idealized rural life and living off the land, Kersting-Lark said.

“That’s still very present in the American dream,” Kersting-Lark said. “Little kids play with farm animal toys, even if they’ve never seen a farm animal in their life. And that’s something we talk to the kids about — how special it is that in rural America, we can see all these animals up close and personal.”

The Importance of Place

In the past, there’s been a prosaic, wry approach to rural development, said Michael Fortunato, a founding partner of Creative Insight Community Development, which specializes in rural and smaller communities. Industry-focused development pushed a goal of keeping populations from declining. Its ethos is that jobs follow people. But growing anecdotal evidence suggests a shift, Fortunato said.

“People aren’t necessarily attracted to places where jobs are growing,” Fortunato said. “They’re attracted to great places. And then they look for a job.”

Rather than the arts developing only after a strong economy, Fortunato said, “now, we’re seeing that flipped upside down, where the arts are seen as fundamental to great placemaking.”

A growing number of states are working with artists and others in creative sectors to build vibrant, rural communities and stimulate economic opportunities, according to a January 2019 Rural Action Guide from the National Governors Association. The guide encourages governors and states to capitalize on existing regional cultural assets, build the state’s cultural and creative partnership infrastructure, develop local talent and human capital with creative skills and create an environment that welcomes investment and innovation.

In 2015, arts and cultural production employed nearly 628,500 workers in—and contributed $67.5 billion to the economies of—states where 30% or more of the population lives in rural areas, according to the National Endowment for the Arts.

In North Carolina, which has the largest rural arts economy, employment for arts and cultural production exceeded 118,000 workers and $13 billion in value-added contributions.

Some distressed postindustrial communities, such as Paducah, Kentucky, have responded to population loss through artist relocation programs, which use incentives such as low-cost housing, zoning for living and working spaces and below-market rents to attract professional artists, according to a 2016 paper Fortunato co-authored in the Journal of Rural Studies.

The program achieved a 10-to-1 return on investment within 10 years on top of using abandoned downtown spaces. Paducah also received a Creative City designation from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, or UNESCO.

Beyond Paducah, a statewide program, Kentucky Main Street, focuses on historic preservation and cultural tourism to stir economic development.

In the South Carolina Low Country, six high poverty counties received a federal Promise Zone designation, which grants them favorable consideration for federal grant applications.

With the designation, DuPlessis, with the arts commission, sought an opportunity to engage more deeply by finding new people to partner with in the region. Arts commissions measure success in part by how much funding goes into particular communities.

But oftentimes, DuPlessis said, rural communities lack the infrastructure or capacity to pursue grants and manage them.

The Promise Zone designation “presented an opportunity for us to engage as a state agency with a new set of people on the ground in communities who maybe weren’t the usual suspects,” DuPlessis said.

With the support of U.S. Department of Agriculture Rural Development funding, the South Carolina Arts Commission identified six leaders, whom they call mavens, in each county to build local teams of residents who were passionate about the community, but weren’t always in positions of power.

“Some of the rural communities we work with are really tired of organizations coming in with solutions, dropping money on a place, nothing significant happening, and then that organization is gone,” DuPlessis said. “Part of what we’re doing is creating pride of place and creating opportunities for people to own their community and see themselves differently.”

Julie Dempsey, South Carolina promise zone coordinator, said she often relies on the mavens as local points of contact. A relationship with a maven in Hampton County resulted in creative stations along a trail that prompt walkers to dance and sing—a boost to wellness and mental health, Dempsey said.

But the arts have limits. Developing an artistic community is a great strategy when you have high confidence local residents will support it, Fortunato said. The arts won’t solve a local drug problem, class divisions or the challenges associated with a lost hospital.

But after years of disinvestment, rural places need additional approaches, said Charles Fluharty, president emeritus of the Rural Policy Research Institute.

“A lot of little things can be far more important than a great big thing,” Fluharty said.

April Simpson is a Staff Writer at Stateline.

NEXT STORY: A State Will Require Civics Education in Prisons