More States and Cities Getting Interested in Ranked Choice Voting

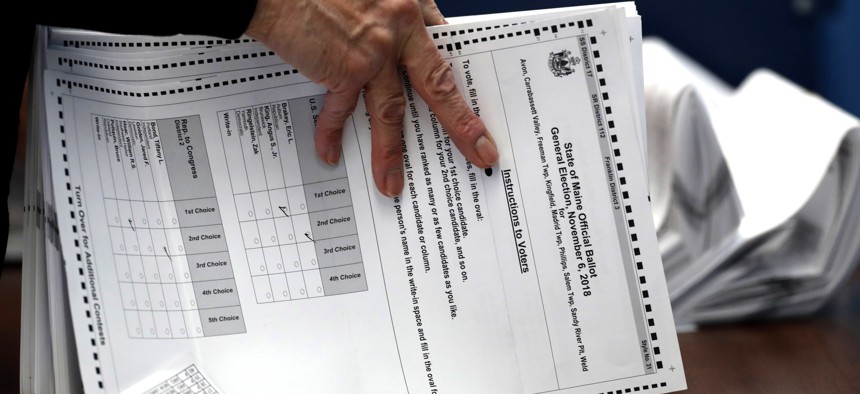

Ballots are prepared for Maine's election in 2018, the first congressional race in American history to be decided by the ranked-choice voting method. Robert F. Bukaty/AP Photo

Proponents say ranked choice voting could lessen polarization and make third party options more viable.

Ranked choice voting has been used in other countries for decades, but is just now starting to gain steam in states and cities across the United States. For individual voters it functions pretty much the same everywhere it’s employed: when filling out a ballot, voters get to rank each candidate in order of preference. Once the votes are tallied, if no candidate wins a majority, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated, and their votes are redistributed to voters’ second choices. The process continues until one candidate receives 51% of the vote.

At an event on Thursday at New America, a nonpartisan think tank in Washington, D.C., a group of electoral scholars and advocates discussed the rise of ranked choice voting around the country, and the potential it carries for addressing salient political problems.

“It is exactly what it sounds like,” said Grace Ramsey, a voter education consultant who explained what ranked choice voting was to Minneapolis residents when the process was new there. “We’d say: your first choice is a candidate you love, your second choice is a candidate you like, and the third choice is a candidate you can stand.”

Minneapolis passed ranked choice voting for municipal elections in 2006, and used it for the first time in 2009. Before, the city had a primary and then a general election to determine their mayor, city councilors, and other elected city leaders. But running two elections was expensive, and the primary usually had a turnout rate of 15%. Changing to a ranked choice system allowed the city to have a less expensive election with more voters participating, Ramsey explained.

Minneapolis isn’t alone. Many cities, including Santa Fe, Oakland, San Francisco, and Cambridge, have implemented ranked choice voting for municipal elections that select mayors, city councilors, city attorneys, municipal judges, and city auditors. A proposal for ranked choice voting will appear as a ballot measure this year in New York City.

In 2018, Maine became the first state to implement ranked choice voting for U.S. House and Senate elections, as well as for the state assembly. In 2020, six states—Iowa, Nevada, Hawaii, Alaska, Kansas, and Wyoming—will use ranked choice voting for the Democratic presidential primary elections in their states. Several other states are considering embracing the system, with a ballot measure approved for 2020 in Massachusetts and possible in California.

Ramsey said that ranked choice voting has the possibility to transform what elections look like. She said that candidates in many places look at voters like a venn diagram: one circle for supporters, one circle for detractors, and a sliver up for grabs in the middle. “That middle is shrinking, so that tactics are getting ugly,” she said. “The conversation has become more about who you’re running against than about who you’re trying to represent.”

Ramsey said that ranked choice voting could make voter bases look more like concentric circles: a small one in the center of supporters who are volunteering and donating, and then outer circles that candidates need to reach to build their base. “It completely shifts the incentives,” she said.

Evan McMullin, the executive director of Stand Up Republic, an organization that advocates for electoral reform, said that division is being used as a political strategy more commonly now, instead of just in deep blue or deep red states. “That’s very alarming and should concern us all,” he said. “Our leaders should work to unite us—and that seems so basic.”

He said that polarization is making it harder to govern, pointing to the difficulty of passing budgets, the lack of solutions to crippling infrastructure problems, and disagreements over the current healthcare system. “That gives rise to extreme leaders who exploit divisions,” he said. “Ranked choice voting is one of a couple of reforms that offers the best opportunities to incentivize leaders to find common ground.”

Christopher Lamar, legal counsel at the Campaign Legal Center, agreed that politicians “come back to the center” when ranked choice voting is established, rather than appealing to the fringes. He said that campaigns that rely on persuasion—where volunteers might knock on doors and turn away if a voter has already aligned with another candidate—could be turned into campaigns of mobilization—wherein volunteers could ask who a voter’s second choice is, and encourage them to vote regardless. “Instead of making sure that the 15% of the people who like one candidate come out to vote, they could focus on the remainder of the voters,” he said.

Lee Drutman, a senior fellow of political reform at New America, said that ranked choice voting also opens up space for third parties. “Voting for a third party won’t be seen as wasting your vote, it would be seen as expressing your voice,” he said.

Drutman pointed to the winner-take-all and first-past-the-post approaches as unusual among modern electoral systems across the globe, many of which are now multiparty democracies. He said that ranked choice voting could “fundamentally solve a lot of the core problems that are roiling our democracy” at the moment—and he thinks it’s a reform that has a chance of reaching a tipping point in the next five to ten years.

Ramsey agreed, saying people may be more open to ideas like ranked choice voting than it seems. “We don’t think to question the status quo, these are systems we’ve been raised to believe have always been around, but we don’t think about how young democracy actually is,” she said. “I think once you give people the opportunity to reconsider, you see a largely positive response...I haven’t yet come across a voter who said ‘everything’s great, let’s not change anything.’”

Emma Coleman is the assistant editor for Route Fifty.

NEXT STORY: Taking The Cops Out Of Mental Health-Related 911 Rescues