Trying to End the Dangerous Practice of Late-Night Jail Releases

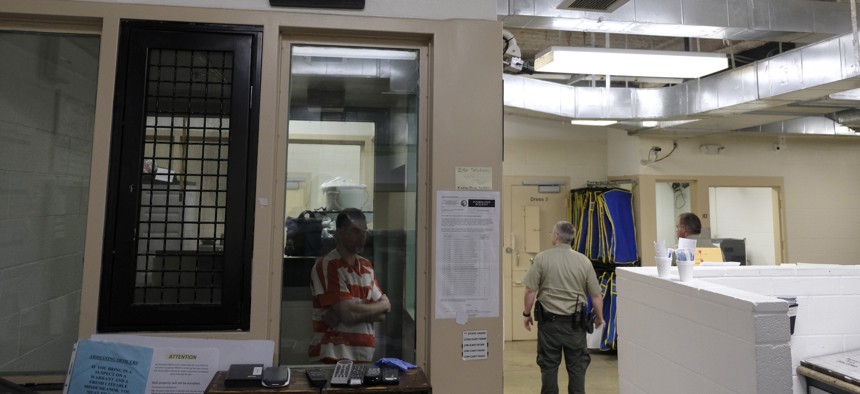

Near the booking area of a California jail. The Getting Home Safe Act would prevent county jails from releasing people in the middle of the night. AP Photo/Eric Risberg

If signed by the governor, a measure passed by the California legislature would require jails to set new release times and provide people with free phone calls to arrange transportation.

In July 2018, Jessica St. Louis, a resident of Berkeley, California, was released from the Santa Rita Jail around 1:30 a.m. She did not have a cell phone, but was given a Bay Area Rapid Transit pass and pointed in the direction of the nearest train station. Four hours later, she was found dead of an opioid overdose.

California state Sen. Nancy Skinner, a Democrat from Berkeley, said her death was preventable. "Releasing people in the dead of night when they may not have a ride or a safe place to go is cruel and unnecessary treatment,” she said in a statement.

Alameda County Sheriff's spokesperson Sgt. Ray Kelly said at the time that St. Louis' death was "an unfortunate situation," but that the jail can’t keep people in custody after they have been released, especially when they are at capacity. Santa Rita Jail usually releases 50 to 100 inmates between 4:30 p.m. and 4:30 a.m. every day.

In response, Skinner wrote the Getting Home Safe Act, which would prevent county jails from releasing people in the middle of the night. The bill passed with overwhelming bipartisan support in both the state House and Senate, and is currently awaiting Gov. Gavin Newsom’s signature. Skinner’s staff said they are optimistic that it will be signed, given Newsom’s support for other criminal justice reform efforts this year.

In addition to setting standard release times across the state, the bill would require jails to provide people locked up for longer than 30 days with a three-day supply of medication and provide transportation to a drug or alcohol rehabilitation program if that has been court-ordered or voluntarily chosen. Anyone scheduled for release between 5 p.m. and 8 a.m. would be given the option to stay for up to 16 additional hours in a safe waiting area. If that is declined, the sheriff’s office would have to provide people with free phone calls or access to a cell phone charging station. The bill would require county jails to track how many people they release at night. It would not impose any new measures on state prisons.

Jessica Bartholow, a policy advocate for the Western Center on Law and Poverty, which helped draft the bill, said the change would particularly help low-income people. “Let’s face it: people being released late at night are not wealthy,” she said. “They’re poor and they have minimal resources. Jessica St. Louis didn’t get a phone call, even though she had family and friends who would have come to pick her up, and she couldn’t afford a cab. Why would what happened to her be the best practice in any county?”

Some opponents of the bill, including sheriffs in rural counties, said the requirements would be burdensome and costly. The bill, which would go into effect in June 2020, notes that because it “would impose new duties on sheriffs and county jails...The California Constitution requires the state to reimburse local agencies...for certain costs mandated by the state.” The measure is estimated to cost $150,000 annually.

Proponents of the bill argue that releasing people in the middle of the night can be dangerous, especially for people with drug addictions and women, who can be vulnerable to exploitation by traffickers.

The Young Women’s Freedom Center, which backed the bill, quoted an 18-year-old who described an abrupt release from jail. Her phone had died during her time in custody, and she didn’t have change to use a pay phone, so she couldn’t contact someone for a ride. "I didn’t know what to do,” she said in a statement. “I sat and waited for a while, hoping someone resourceful would come into the building. Time continued to pass and no one came in, so I decided to just start walking in the direction of BART. It was almost one o’clock in the morning."

California already passed a similar bill in 2014 which allowed sheriff’s offices to voluntarily establish release procedures similar to those proposed in the current bill, but few made the decision to do so.

Other states and localities have also taken up the issue, but with mixed results. Lawmakers in Texas tried and failed to pass similar legislation in 2011 and in 2017. Washington, D.C. passed a law requiring the local jail to halt releases between 10 p.m. and 7 a.m., but a federal judge found it unconstitutional because it held people past their release dates. D.C. then amended their law to require the jail to ensure that those released after 10 p.m. have housing and transportation from the facility, or to offer that they can stay until 7 a.m., but only if they sign a waiver saying the extension of their stay was voluntary.

Bartholow said that she was surprised by the reception the bill got in California. When it was introduced, the Senate adjourned in memory for Jessica St. Louis, which Bartholow said usually only happens for famous people. “Nobody would want their sister, their mother, their brother to be let out in these conditions,” she said. “This bill really honors Jessica because it ensures that people have the best chance possible when they’re released. If it had been in place before, would Jessica have died? No. That’s the test of its power.”

Emma Coleman is the assistant editor for Route Fifty.

NEXT STORY: Tackling the Teacher-Student Diversity Gap in K-12 Schools