Border Towns are Pushing for a Complete 2020 Count

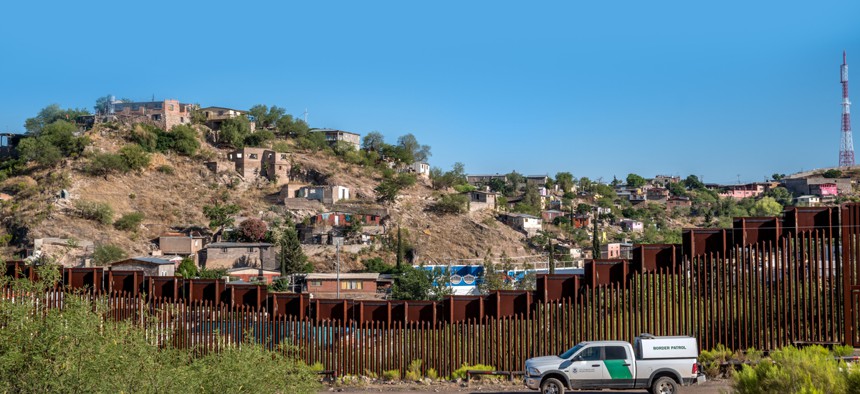

Since the colonias can be hard to find, the U.S. Census Bureau and local communities like Hidalgo County used aerial photography to help chart new addresses that need to be contacted next year. Shutterstock

For communities with high immigrant populations, an undercount of the 2020 census could sap both political representation and federal funding.

This article originally appeared on Stateline, an initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts.

HIDALGO COUNTY, Texas — In this colonia near the Mexico border, an area of sometimes makeshift housing south of Edinburg, neighborhood residents are learning when to, and when not to, speak up to authorities when you’re living in the country illegally.

Caught driving without a license? “What do you do? We’ve told you! Don’t say anything, don’t sign anything,” said Cristela Rocha, a community organizer for the immigrant advocacy group LUPE, La Union del Pueblo Entero, at a recent gathering with residents.

But when it comes to next year’s census? That’s the time to be as forthcoming as possible: Fill out forms on the age and race of everyone who lives with you, even distant relatives or a friend sleeping in your shed or garage.

The community meeting, organized by LUPE, highlights the problem communities face in high-immigrant areas seeking to avoid an undercount in the 2020 census, a problem that can sap both political representation and federal funding.

A colonia is one of the lowest rungs on the ladder of the American Dream. Newcomers, typically immigrants from Mexico who often do not have legal status, buy a plot of land and live in makeshift housing while they pay off the loan. Eventually, some of them build permanent houses, mostly by themselves or with the help of neighbors.

Since the colonias can be hard to find, the U.S. Census Bureau and local communities like Hidalgo County used aerial photography to help chart new addresses that need to be contacted next year.

The University of New Mexico Bureau of Business and Economic Research, concerned that the lack of information about colonias was hampering efforts to get federal dollars for improving them, launched an independent project to find and study them after the 2010 census.

In Arizona, local activists are leading the way in publicizing the need for census participation but face cuts in funding since 2010, said Deyanira Nevárez Martínez, a University of California, Irvine, researcher who led a study on the state’s colonias published in October.

“The activists and the leaders within the community understand the importance of making sure everybody gets counted,” Nevárez Martínez said, “but, unfortunately, there is not much trust in the current administration, which will inevitably have an effect on the count.”

Texas and New Mexico have 25 of the 37 Hispanic-majority counties deemed hardest to count, according to a 2017 University of New Hampshire study. In those places, fewer than 73% of census forms were returned in 2010; many of them are rural border counties like Hidalgo that host colonias.

Getting word out to cooperate with the census, even though it goes against the instinct to stay under the radar for immigrants who may be living here illegally, is serious business all over the country, but especially in the colonias. In the current anti-immigrant climate, even people who are here legally may be reluctant to cooperate, especially if a member of their household is here illegally.

“You need to stand up and be counted. You can’t vote if you’re not a citizen, but in this case, you do count. The government needs to know where you are, so we can get the resources you need,” said Martha Sanchez, LUPE’s community organizing coordinator, during the census awareness meeting for residents in the Rincon del Valle colonia near Edinburg, Texas.

Hidalgo County officials think the census missed as many as 20% to 30% of its residents in 2010, costing it as much as $210 million in federal funds over the decade. For instance, the county later found 152 homes in a colonia where the census had counted 14 people, suggesting that hundreds of people may have been missed there alone.

Colonias are especially prevalent in South Texas and Hidalgo County, which has nearly half of the nation’s 2,000 makeshift communities, more than any other county in the United States.

“Sadly, I think the majority of those [uncounted people] were noncitizens who are afraid for it to be known that they’re here,” said Hidalgo County Judge Richard Cortez, the county’s highest elected official. “That’s a very significant amount of money we’re missing out on to serve the people.”

The county plans to spend $300,000 on census outreach and already has used aerial photography to add thousands of new addresses in the colonias and elsewhere to the Census Bureau’s list of homes to be counted, Cortez said. Others in the county, including local schools and the city of Pharr, are planning their own campaigns.

“We had no idea what was going on in 2010. This time we’re going to hire people to follow the census-takers around and make sure they get everybody,” said Pharr City Commissioner Daniel Chavez, who grew up in a Pharr colonia named Las Milpas.

In Texas, local governments are on their own on outreach, though a statewide network of nonprofits is raising money to help them get the word out.

“As far as anybody knows, the census came through in 2010 and never talked to anybody,” said Cynthia Garza Reyes, director of external affairs for the city of Pharr. “They brought in people from Florida. They had no idea what they were doing.”

Texas colonias have matured since the days when they were essentially shantytowns for migrant workers near fields, said Jordana Barton, who studies them for the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

“I’ve seen people make houses out of campaign signs,” Garza Reyes said, “or the roof of an old church with just dirt underneath.”

Today’s colonia residents are still mostly Hispanic, but more than 60% of adults and 94% of children are U.S. citizens. As citizenship rates grow and colonias evolve into working-class neighborhoods with political clout, residents are more sensitive to the need for a full census count, Barton said.

“I’m sure they’re going to double down on this next year,” she said, adding that there’s a growing awareness of infrastructure needs that others might take for granted, such as broadband and streetlights.

The population of Hidalgo County has grown by about 10% to 861,000 since 2010, according to 2017 census estimates, and county officials hope a complete count could top 1 million.

The colonias of the city of Pharr are a success story. They have gotten help, such as streetlights, since the city annexed the areas more than 30 years ago. Even so, the tradition of homemade housing continues and there are collapsing roofs and overcrowded rentals without enough bathrooms.

Today’s colonia residents are not as likely to be farmworkers, and there’s lucrative work in oil fields for many with legal work status willing to commute, which is why there are new pickup trucks and the occasional Mercedes-Benz in the driveways, said Chavez, the Pharr commissioner.

Chavez was born in Idaho, where his migrant farmworker parents picked hops part of the year. As a child, he lived mostly here in the Las Milpas area, in what began as a slowly growing shelter made of wood panels from a flea market.

“A shower was holding a hose over your head,” Chavez recalled. “My dad set up a little area with a curtain for that. For a bath, you heated water on the stove. The bathroom was an outhouse over a hole in the ground.” He wore plastic bags over his school shoes because of the mud — no sidewalks or pavement — and school buses had containers to store the bags.

Now 41, Chavez has a college degree and owns a construction and lighting businesses. He stayed in the neighborhood, marrying a childhood sweetheart who lived next door, and built a two-story home for himself and his parents.

He lived in a succession of more elaborate houses over the years. Now his home looks more like a McMansion than a makeshift shack, but it was still a community effort to build.

“My dad did that roof. Look how nice!” Chavez said. “We made it ourselves, but everybody pitches in — the guy across the street knows concrete; another guy knows plumbing.”

In some ways, incorporation by the city of Pharr 25 years ago put an end to Las Milpas as a colonia, and some refer to the area now as “South Pharr.”

“The only reason we talk about Las Milpas and colonias is that we were here 20 years ago,” Chavez said. “That’s not really what it is now.”

Still, even in today’s Las Milpas there is fear of authorities among new immigrants.

A parents meeting was scheduled at night during a rainstorm recently, and in the chaos of people looking for parking spaces a neighbor called the police.

“I said, ‘Where is everybody?’ They went home,” said Norma Garza, a parental engagement coordinator for the local school district. “Two police cars came and that was too much. We’re not allowed to ask anybody about where they’re from, but right then I said, ‘OK, we’ve got some immigrants here.’”

In the Rincon del Valle colonia, where residents gathered to hear about the census, most expressed concern about police stopping them for no apparent reason.

“This is how most people get deported, by getting pulled over for driving without a license,” said Sanchez, the LUPE coordinator.

At the same time, the residents all said they understood that being counted by the census meant more money for their neighborhood.

Maria Ordóñez’s family built the first house here in the Rincon del Valle colonia in the early 1990s, and she and other pioneers endured pitch-black nights without streetlights and roads that flooded because of poor drainage, preventing school buses from reaching their homes. The neighborhood is about 15 miles from the Mexican border.

The border has been a source of economic life for this county, especially after 1994 when NAFTA brought more trade and cross-border factories sharing production. The city of Pharr, which owns a private commercial highway to Mexico, makes more than $1 million a month in revenue from tolls, Chavez said.

Shoppers from Mexico aldso have fueled a retail boom in Hidalgo County, said Garza Reyes, the Pharr external affairs director.

“I go over here to the department store and I might buy one dress,” Garza Reyes said, “but a Mexican shopper will buy every color and size and take it back home to sell.”

Even the fear of immigration authorities is receding in the old colonias, said Chavez, adding that his construction and lighting companies have done work for Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Customs and U.S. Border Protection offices locally.

“ICE isn’t the enemy. Border Patrol isn’t the enemy,” Chavez said. “A lot of the children of the colonias grow up and go to work for them.”

Tim Henderson is a staff writer for Stateline.

NEXT STORY: A Green New Deal for Public Housing