Concerned About Her City's Lack of Affordable Housing, a Councilwoman Decided to Build Some

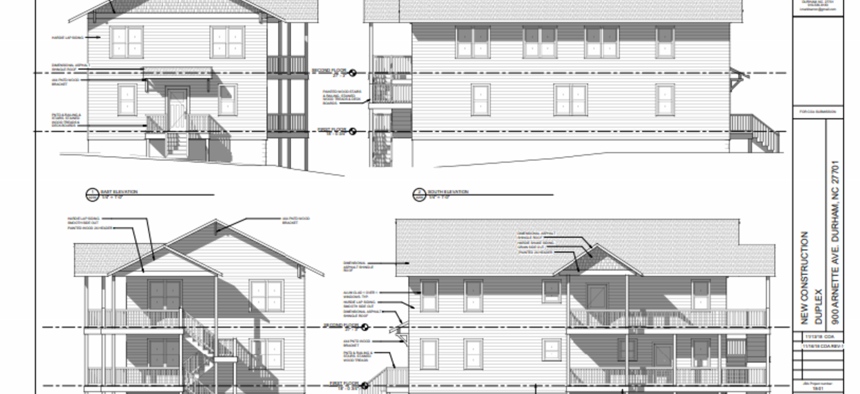

Blueprints for Jillian Johnson's proposed "micro-development" project, a two-unit duplex that will serve as affordable housing in her Durham neighborhood. Jillian Johnson

Jillian Johnson, mayor pro tem of Durham, N.C., is constructing a duplex next to her house with the goal of renting its two units to low-income families who need stable housing.

As a community organizer and a member of the Durham City Council, Jillian Johnson has for years advocated about the need for more affordable housing in her hometown. In November, two weeks after getting re-elected to a second term, the mayor pro tem broke ground on her own affordable housing project: a duplex, constructed on the vacant lot adjacent to her home.

“I’ve always wanted to put my values into practice,” Johnson said. “Being in elected office for me is part of putting my values into practice, and building affordable housing next to my home is part of that as well. I want to be someone who contributes in a positive way to my community.”

Johnson sees the “micro-development” project, which will most likely be completed by the end of next year, as a tangible way to encourage city residents to employ creative solutions to the shortage of affordable housing in Durham. According to data from the city, Durham currently has about 8,600 income-restricted affordable units. It would need more than 16,000 affordable housing units—nearly twice the existing supply—to meet the needs of low-income households that are spending more than half of their income on housing.

“That number will likely increase as housing costs in Durham continue to rise, given that the majority of low-income households in the city need to live in privately owned, non-income restricted units that may become increasingly expensive over time,” the city’s Department of Community Development wrote in an informational document for residents ahead of a November vote on a $95 million affordable housing bond referendum.

Voters passed that referendum, which will fund a host of measures, including the construction of 1,600 new affordable housing units, stabilization of existing low-income renters and homeowners and moving 1,700 homeless households into permanent residences. That large-scale initiative is a step in the right direction, Johnson said, but it’s unlikely to solve the crisis on its own.

“We are not going to be able to meet the needs of all of our residents just with city resources, or the resources that we can provide to nonprofits,” she said. “We need to make it easier and we need to encourage residents to do these types of projects—to build on land they own, to put an affordable home on their lot or construct an accessory unit on the back of their house. Doing this sort of urban in-fill project in our neighborhood is really critical to meeting our affordable housing goals.”

By developing her own small-scale affordable property, Johnson hopes to inspire other residents to do the same. But the project is not without headaches, even for someone well acquainted with local government bureaucracy.

Johnson’s home is located in a historic district, so the project design required approval from the city’s Historic Preservation Commission. The lot is adjacent to an abandoned right-of-way, which also meant extra red tape. All told, Johnson spent several years designing the duplex and going through the proper channels to be able to start construction.

“The main challenges have been how to figure out the various regulatory processes, which is good for me—to be able to experience that the way a developer would,” she said. “It’s given me some insight on how those processes work within the city.”

There’s also financial risk, Johnson said. She hopes to offer the completed property—two 1,300-square-foot three-bedroom, two-bathroom units—at rents that would be affordable to a family of four making a combined $68,000, or 80 percent of the area’s median income. That target means she will likely lose money on the duplex for the first few years it’s rented, she said.

“I’ve never owned a rental property before, so I am definitely going to be learning as I go about how to do that. There’s a financial risk, and a risk that this will consume a lot of my time,” she said. “But I had this resource, this land, and wanted to put that to work in a way that reflected my values and my goals for my neighborhood, and for the Durham community more broadly.”

To promote the project, Johnson plans to post Twitter updates under the hashtag #skinnyduplex, a term coined by her 13-year-old due to the long rectangular shape of the lot. She’s posted three updates so far, including a short video of a backhoe moving earth and a screenshot of the building’s blueprints.

IT’S HAPPENING! There is more earth-moving power than existed in the entire ancient world in my yard right now. My new hashtag #skinnyduplex will chronicle my attempt to micro-develop one small affordable duplex next to my house in central Durham. Stay tuned! pic.twitter.com/PHcG3Bxyq1

— Jillian Johnson (@JillianDURM) November 19, 2019

In addition to chronicling her progress, Johnson is hopeful that the tweets will help drive the larger conversation about creative solutions to housing problems, particularly following recent zoning changes that should make it easier for residents to pursue similar projects.

“I hope we’ll see more and more people doing this now that the housing situation is getting increasingly scarce and since we’ve made it easier via the zoning code,” she said. “I want to be a part of the solution and to encourage other people to do the same.”

Kate Elizabeth Queram is a Staff Correspondent for Route Fifty and is based in Washington, D.C.

NEXT STORY: Almost 700,000 to Lose Food Stamp Benefits Under Finalized Trump Administration Rule