Why the Iowa Caucus Birthed a Thousand Conspiracy Theories

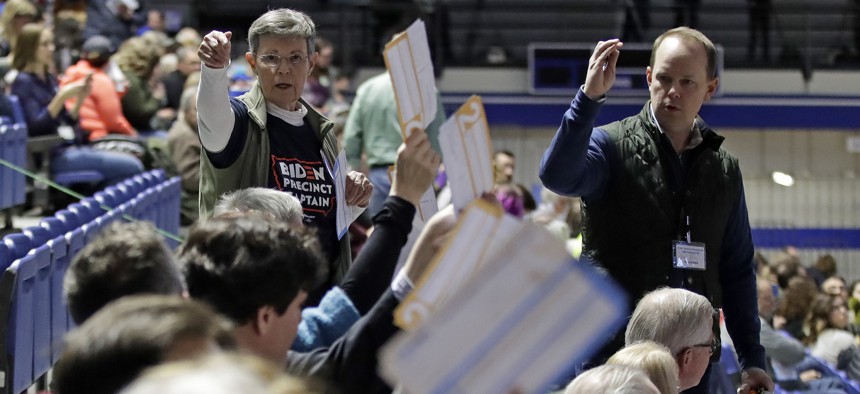

Precinct 68 Iowa Caucus voters seated in the Biden section hold up their first votes as they of the caucus as they are counted at the Knapp Center on the Drake University campus in Des Moines, Iowa, Monday, Feb. 3, 2020. AP Photo

COMMENTARY | A panicked electorate is more susceptible to believing claims without evidence.

Politics, like nature, abhors a vacuum, and in the absence of results from the Iowa caucus, a range of conspiracy theories have sprouted.

As of this morning, results from last night’s caucus are still outstanding. The Iowa Democratic Party blames that on the failures of a new app it rolled out to gather results from across the state. It’s still impossible to know quite what happened, in part because the party has given out so little information about what went wrong.

That has created a perfect environment for conspiracy theories to spread. The whispers are coming from President Donald Trump’s election campaign, from Democratic members of Congress, from New York Times opinion writers, and from ordinary Americans who are frustrated or freaked out or simply trolling. In a country where wild beliefs are already rampant, with the president himself setting the pace; where there are fewer and fewer common, trusted sources of information; and where the stakes of politics feel perpetually life-or-death, these conspiracies can find a receptive audience and be especially damaging.

The best available information right now suggests that the Iowa Democratic Party just disastrously mismanaged the election. Many observers, including my colleague Elaine Godfrey, reported ahead of time on the fears that a combination of new caucus rules and the new app might produce a mess.

“It looks like incompetence,” Rick Hasen, an expert on election laws at UC Irvine and the author of the new, and fortuitously timed, book Election Meltdown, told me. Hasen noted that the caucus is run not by state officials but by the state Democratic Party, which doesn’t necessarily have the capacity to handle such a major event. “This is the one time every four years that the eyes of the world are on Iowa. They really screwed it up. This stuff shouldn’t be rocket science, but a caucus is a very complicated thing.”

Nonetheless, “I find the claims of intentional rigging to be irresponsible and dangerous,” Hasen said.

The theories range from the specific to the very vague. Given documented Russian interference in the 2016 and 2020 elections, some people immediately feared the Kremlin’s hand at work. There is at this point no evidence that is true; the failures of the app in Iowa seem to come down to a piece of technology that wasn’t up to snuff. The president, who has long denied that Russia interfered in the 2016 election—though his administration otherwise uniformly acknowledges it—mocked the idea, tweeting, “When will the Democrats start blaming RUSSIA, RUSSIA, RUSSIA, instead of their own incompetence for the voting disaster that just happened in the Great State of Iowa?”

Yet his own campaign is at the same time discounting mere incompetence as the cause, and spreading conspiracy theories of its own. “Mark my words, they are rigging this thing,” Eric Trump tweeted, while his brother added, “The fix is in ... AGAIN.” (Their father repeatedly claimed ahead of the 2016 election, without evidence, that the election was “rigged,” and he has falsely claimed millions of ballots were cast by ineligible voters.) A campaign spokesperson asked whether the race was “being rigged against Bernie Sanders.”

Some Sanders fans have been particularly skeptical of the snafu. Sanders was expected to win or place very high in the caucus, and they claim that the Democratic Party engineered the fiasco to stop him. Another, related conspiracy theory centers on the app itself. The app is a product of a company called—I am not making this up—Shadow. In July, the campaign of Pete Buttigieg also paid Shadow $43,000 for software rights and subscriptions. Last night, despite the lack of official results, Buttigieg claimed Iowa as “a victory” for his campaign, based on preliminary results and entrance polling.

Thus the theory, advanced by Representative Ilhan Omar, a Sanders endorser: Buttigieg was in league with Shadow, which failed, allowing him to declare a win. But it’s not uncommon for campaign tech vendors to work with multiple campaigns and other entities like state parties, and the bad press that Shadow is receiving for the Iowa debacle will surely cost it far more than $43,000.

Like the best conspiracy theories, these are all grounded in some truth. Russia really did interfere in previous elections. Democratic Party leaders clearly did favor Hillary Clinton in 2016, and Politico reported just last week on an effort by Democratic National Committee members to change convention rules in an attempt to keep Sanders from winning the nomination this time. Buttigieg really did pay Shadow. But like all conspiracy theories, these ones also lack evidence to back them up. (If they were proven, they wouldn’t be conspiracy theories.)

Americans, though, are primed to believe them. Look no further than Trump, who was just impeached in part for pursuing a bogus theory that Ukraine, and not Russia, interfered in the 2016 election. As a Pew Research Center report last month found, the population trusts only a few media outlets to deliver accurate news. This is especially true of the divide between Republicans and Democrats, but it’s also true within the parties: Supporters of certain candidates, especially anti-establishment ones like Sanders and Andrew Yang, view the media as biased against their champions.

Meanwhile, powerful figures like Trump amplify and in some cases manufacture baseless claims that their partisans then believe. Misinformation undermines democratic government at all times, but it is particularly dangerous once voting starts.

“We take peaceful transitions of power in our democracy for granted,” Hasen said. “The election system is more fragile than people believe. When things are this close and they’re this heated, because we’ve had so many debacles in how our elections are run, it becomes fodder for people to doubt the process.”

That is especially true now, when the stakes of elections feel not only high but existential. As my colleague Yoni Appelbaum reported last year, two-thirds of 2016 Trump voters viewed the election as the last chance to stop American decline. And while they remain apocalyptic, many Democrats now seem to feel the same way about this race. The obsession among Democratic voters about choosing a candidate who can beat Trump points to the state of fear in the electorate. A panicked electorate is more susceptible to believing claims without evidence.

Perhaps the reaction to the Iowa debacle offers a preview of what the United States faces during the next nine months. But with each episode that weakens trust in the election process, it gets a little less likely that there will be a tidy end to the election in November.

David A. Graham is a staff writer at The Atlantic.

NEXT STORY: After Iowa Voting App Struggles, Experts Warn of Dangers with New Election Tech