Switch to Remote Learning Could Leave Students With Disabilities Behind

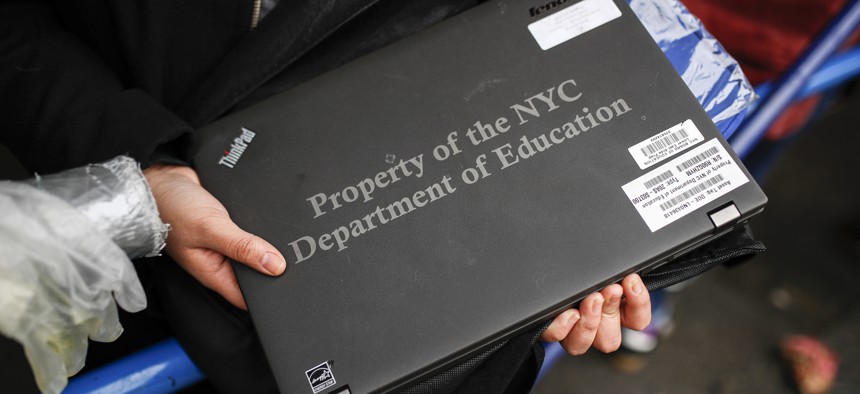

A student receives her school laptop for home study at the Lower East Side Preparatory School in New York. AP Photo

The U.S. Department of Education has told districts that they should not let concerns over how to reach students with disabilities stop them from offering distance learning.

This story was originally published on Stateline, an initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts.

School leaders are grappling with how to deliver special education services—and stay compliant with state and federal civil rights law—as governors shut down school buildings to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus.

A handful of districts announced in recent weeks that they won’t yet require distance learning because they haven’t figured out a way to serve all students, including students with disabilities, English Language Learners and students who don’t have internet access at home.

The U.S. Department of Education told schools Saturday that they should not let concerns over how to reach students with disabilities stop them from offering distance learning, and that they don’t have to reach all students the same way.

"It was extremely disappointing to hear that some school districts were using information from the Department of Education as an excuse not to educate kids," Secretary Betsy DeVos said in a statement. "This is a time for creativity and an opportunity to pursue as much flexibility as possible so that learning continues. It is a time for all of us to pull together to do what's right for our nation's students."

For instance, the department's fact sheet said, teachers could read out written assignments to blind students over the phone, or teachers could provide such students with an audio recording of the document.

The department told schools two weeks ago that if they’re completely closed because of the coronavirus, they don’t have to offer special education. But if schools are still providing education services, they must give students with disabilities equal access to the same opportunities.

The guidance gave districts some wiggle room: “The Department understands there may be exceptional circumstances that could affect how a particular service is provided.”

But confusion persisted, and states asked for more guidance, said Kathleen Airhart, program director for special education outcomes at the Council of Chief State School Officers, a Washington, D.C.-based organization of officials who head state education departments.

Airhart said Monday that she hadn’t yet spoken to enough state leaders to know if the new fact sheet answers all their questions. But, she said, it should help.

“I think it provides a lot of clarity to states,” she said.

Congress is debating the matter, too. As of Monday morning, the U.S. Senate relief package would require DeVos to recommend possible waivers to legal protections for students with disabilities, to give states “limited flexibility” to serve such students during the pandemic.

Disability rights advocates say winding back core civil rights protections is a bad idea.

“Times of crisis are not times to roll back civil rights, it’s time to roll up your sleeves and figure out how to make things work,” said Wendy Tucker, senior director of policy for the National Center for Special Education in Charter Schools, a New York City-based advocacy group.

Confusion over how to best serve students with disabilities may deepen as governors extend school closures. Kansas Gov. Laura Kelly, a Democrat, last week became the first governor to close schools through the end of the academic year.

Forty-six states have temporarily closed schools in response to the coronavirus pandemic, according to Education Week, a nonprofit education news outlet.

The School District of Philadelphia isn’t providing formal, graded instruction during the two-week period Gov. Tom Wolf, a Democrat, closed schools, citing concerns over how to serve students with special needs and low-income students who lack internet access at home.

“If we can’t provide for all, we can’t provide formal education for some,” said Monica Lewis, deputy chief of communications for the district.

The district has posted learning guides for key subjects online and has encouraged teachers to stay in touch with students.

The Northshore School District, just north of Seattle, closed schools and switched to online learning in early March after some employees and a parent were exposed to COVID-19. But after Democratic Gov. Jay Inslee closed public schools for six weeks, district leaders suspended formal instruction over equity concerns.

“We would risk state and federal monies, because we wouldn’t be able to meet rules and regulations related to certain programs in the district,” said Superintendent Michelle Reid. She declined to say which student group, or program, was at issue, saying she didn’t want to make it a focal point.

Some school leaders also are worried about providing the correct documentation for the services they’re providing special education students during the pandemic, said Lauren Morando Rhim, executive director and co-founder of the National Center for Special Education in Charter Schools.

State leaders are trying to provide answers. “We have staff working around the clock to develop guidance for school districts regarding how to effectively and equitably serve all students during this time, including students with disabilities,” said Katy Payne, director of communications and community outreach for the Washington Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, in an email to Stateline.

About 6.7 million public school students, or 4.6% of all public school students, have a disability, according to the latest federal data. Conditions range from autism, deafness and developmental delays to specific learning disabilities such as dyslexia.

Some advocates stress that schools have an obligation to serve students with disabilities even when their doors are closed.

“Students with disabilities have a right to services, and it’s not dependent on whether the school district is open,” said Ron Hager, managing attorney for education and employment at the Washington, D.C.-based National Disability Rights Network. “For example, students with disabilities can get services during the summer.”

Services such as occupational therapy, speech therapy and behavioral counseling can be hard to provide online, he said, but some can be offered over the phone or videoconference.

Teachers can design remote lessons that reach students with a range of learning abilities, said Sean Smith, a professor of special education at the University of Kansas who studies online learning and helps teachers use technology in their lesson plans.

For instance, he said, teachers might assign a textbook reading but supplement it with video narration that helps struggling readers understand the content. Teachers could give students a variety of ways to show their learning, from essays to virtual presentations.

But teachers may not be able to reach all students virtually.

Lisa Lightner’s 13-year-old son, for instance, has a rare chromosomal disorder and doesn’t focus well on screens. “He definitely needs the one-to-one, in-person learning,” said Lightner, a special education advocate who lives in the Philadelphia suburbs. Her son attends a private school for students with disabilities.

But in-person learning isn’t feasible when people must keep their distance from each other, she said.

“There are a lot of hard-liners who say, if you’re going to advocate for civil rights, then everyone’s needs have to be met,” she said. “But as just a person, I don’t feel that my son should hold up the rest of the community.”

NEXT STORY: Real ID Deadline Postponed Due to Coronavirus